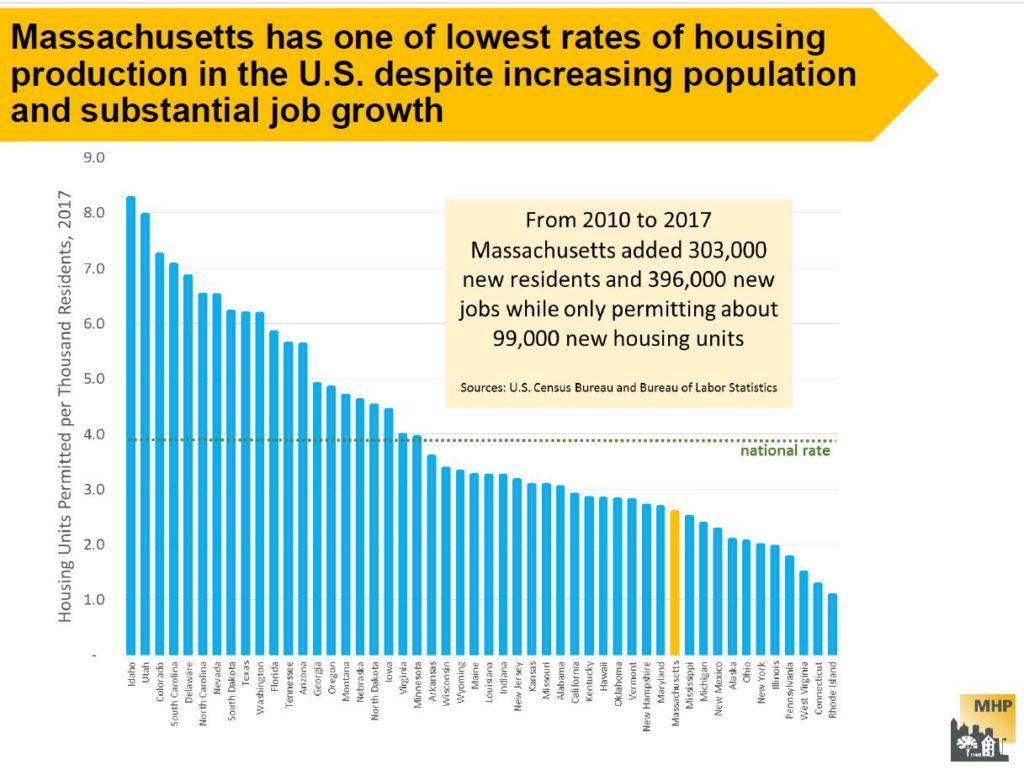

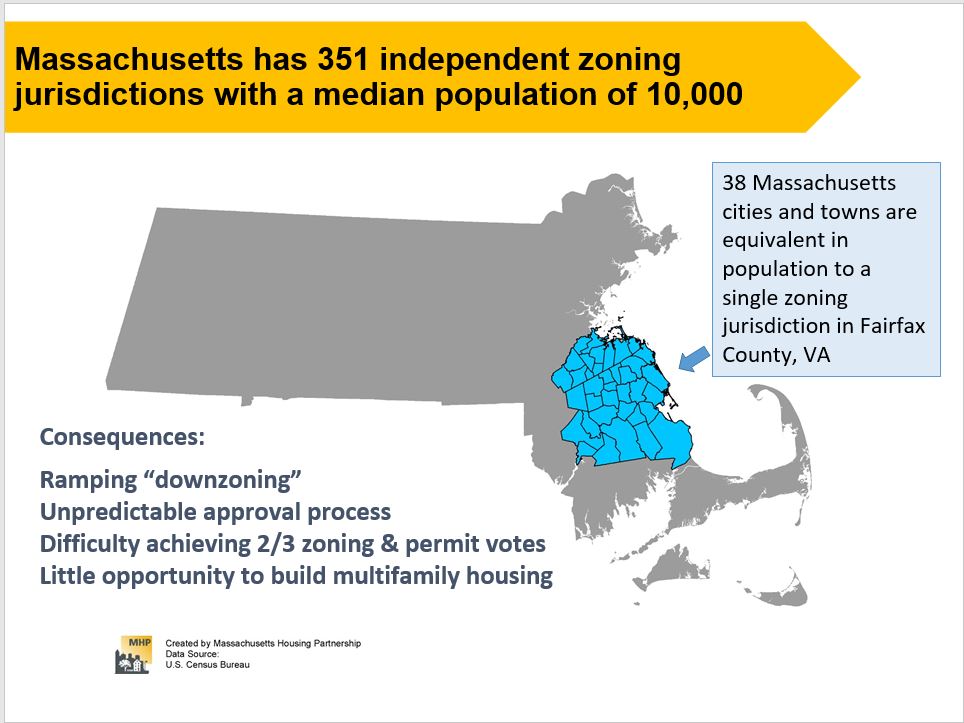

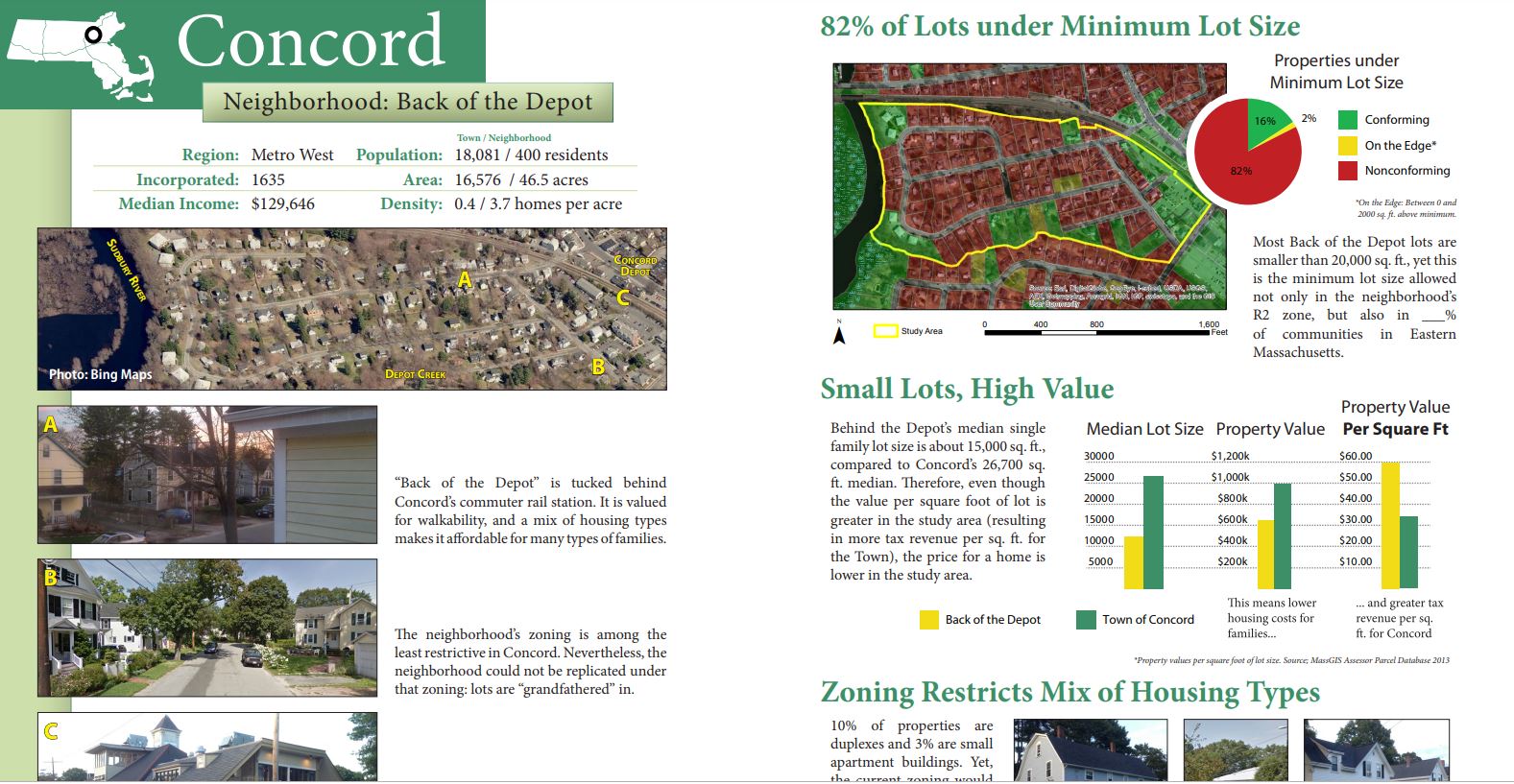

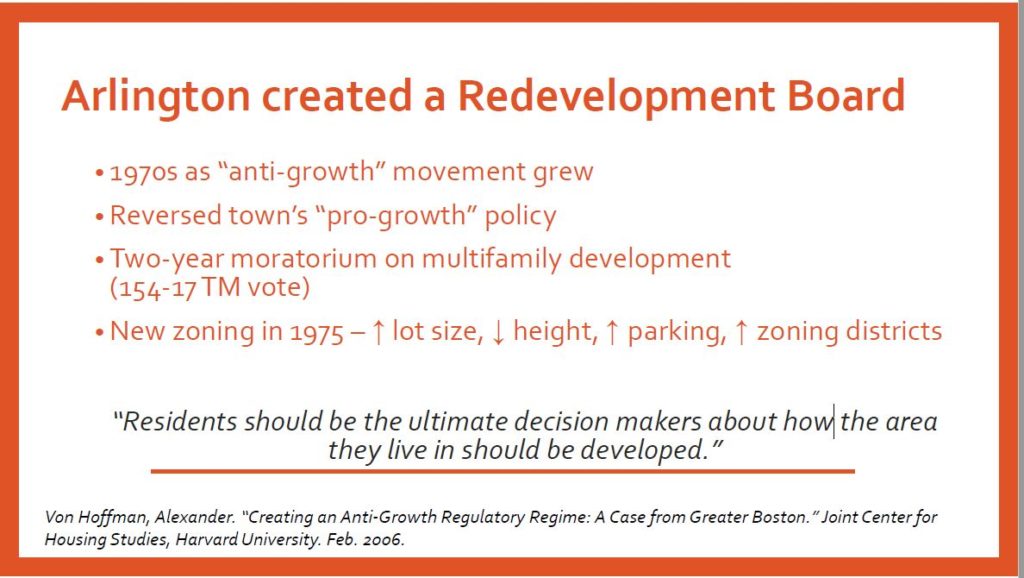

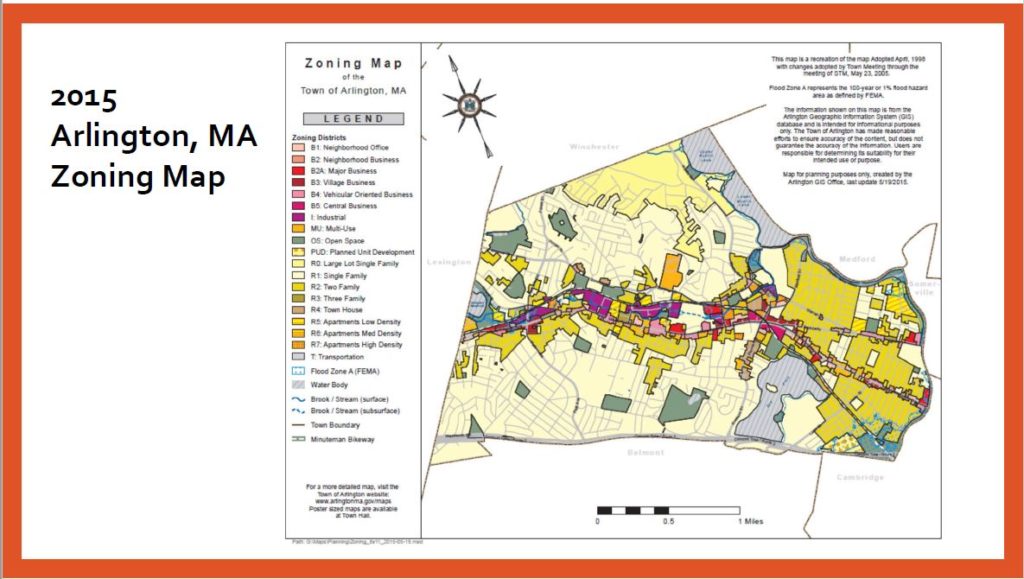

Data in a Mass Housing Partnership report shows how far behind the Boston metropolitan area has fallen in meeting the housing needs of its citizens. There are four primary categories for measuring the inadequacies: 1. Availability, 2. Affordability, 3. L0cation and Mobility and 4. Equitability. See the full report for more data and examples. Two slides are shown below.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel