The new proposal is just the most recent step in a process that reaches back almost a decade, culminating in the Master Plan (2015), the Housing Production Plan (2016) and the mixed-using zoning amendments of 2016. The Town has consistently proposed smart growth: more development along Arlington’s transit corridors to increase the tax base, stimulate local commerce, and provide more varied housing opportunities for everyone, including low and moderate income Arlingtonians. This year’s proposals are no head-long rush into change. Today’s debate is similar to the debate before Town Meeting three years ago. If anything, progress has been frustratingly slow. To realize the Master Plan’s vision of a vibrant Arlington with diverse housing types for a diverse population, we must stay the course on which we have been embarked for so long.

Related articles

A few days ago, the Boston Globe ran an article titled “2021 set records in Boston Housing Market. What now?“. It’s not unusual to see stories about housing in the news — the market is highly competitive and the sale prices can be jaw dropping. Jaw dropping can take several forms: from the new (and used) homes that sell for over two million dollars, to the amount of money that someone will pay to purchase a small post-war cape (around $900,000, give or take).

According to the globe article, the Greater Boston Association of Realtors estimates that the median price of a single family homes in the Boston area rose 10.5% in 2021, to $750,000. Arlington is comfortably in the upper half of this median: according to our draft housing production plan the median sale price of our single family homes was $862,500 in 2020, and rose to $960,000 in the first half of 2021 (see page 39).

In June 2021, I got myself into a habit of sampling real estate sales listed in the Arlington Advocate, and compiling them into a spreadsheet. My observations are generally consistent with the sources cited above; Arlington’s housing is expensive and it’s appreciated rapidly, particularly in the last 6–10 years. It’s a great time for existing owners, but less so if you’re in the market for your first home.

We’re actually facing two problems, which are related but not identical. The first is high cost, which creates financial stress and a barrier to entry (though it is a boon for those who sell). The second problem is quantity; there are regional and national housing shortages, and that contributes to high prices and bidding wars.

Addressing these challenges will require collective effort on behalf of all communities in the metro area; this is a regional problem and we’ll all have to pitch in. There isn’t a single recipe for what “pitching in” means, but here are some for what communities can do.

First, produce more affordable housing. Affordable housing is a complex regulatory subject, but it basically boils down to two things: (1) the housing is reserved for households with lower incomes than the area as a whole, and (2) there’s a deed restriction (or similar) that prevents it from being sold or rented at market rates. Affordable housing usually costs more to produce than it generates in income, and the difference has to be made up with subsidies. It takes money.

Second, simply produce more housing. This is the obvious way to address an absolute shortage in the number of dwellings available. Some communities have set goals for housing production. Under the Walsh administration, Boston set a goal of producing 69,000 new housing units by 2030. Somerville’s goal is 6000 new housing units, and Cambridge’s is 12,500 (page 152 of pdf). To the best of my knowledge, Arlington has not set a numeric housing production goal, but it’s something I’d like to see us do.

Finally, communities could be more flexible with the types of housing they allow. Arlington is predominantly zoned for single- and two-family homes. The median sale price of our single family homes was $960,000 during the first half of 2021, and a large portion of that comes from the cost of land. That’s the reality we have, and the existing housing costs what it costs. So, we might consider allowing more types of “missing middle” housing, where the per dwelling costs tend to be lower: apartments, town houses, triple-deckers, and the like.

Of course, this assumes that our high cost of housing is a problem that needs to be solved; we could always decide that it isn’t. In the United States, home ownership is seen as a way to build equity and wealth. It’s certainly been fulfilling that objective, especially in recent years.

by JP Lewicke

When you love the place you live and you want to help it become even better, how can you make a difference? Arlington is an extremely civically active community, with hundreds of residents involved in Town Meeting, several dozen boards and committees, and numerous other groups that play an important role in improving our town. The vast array of options can be a bit dizzying for a newcomer to sort through.

Fortunately, Arlington has recently launched Arlington Civic Academy to provide interested residents with a pathway to becoming more civically literate and involved. Ably organized by Joan Roman, Arlington’s Public Information Officer, Civic Academy takes place over the course of six weeks and aims to provide participants with the information they need for constructive civic engagement. Applications are open from now until August 4th for the fall session, which will take place between September 12th and October 17th.

Find Out How the Town Works

It’s clear that town government takes the Academy seriously. The Town Manager, Select Board Chair, Town Moderator, and the heads of several town departments have stayed late into the evening to attend Civic Academy sessions. Their formal presentations do a great job of explaining how different areas of town government work and how best to get involved, but the chance to meet them and ask them questions is equally valuable. The participants usually have a lot of very insightful questions, and it’s a great opportunity to learn more and become a more effective advocate in the future.

Participants Make Arlington Civic Academy Great

The other participants are another great part of the program. It’s also a great chance to make connections with other people who are equally enthusiastic about learning and getting involved in making their town a better place. There have been two sessions of the program so far, and several participants have gone on to run for Town Meeting, join the Master Plan Update Advisory Committee, volunteer for last fall’s tax override campaign, and propose warrant articles. We just had a get-together for members of both Civic Academy sessions to meet each other and network, and are hopeful that Civic Academy alumni can help connect future participants in the program to opportunities to get involved in helping Arlington become even better.

Helping Others Learn to Navigate Town Processes

I ran for Town Meeting this spring after attending Civic Academy last fall, and I found that it served me well after I was elected. It taught me how the budgeting process worked, including all the steps from the Town Manager’s office working with individual departments, the Finance Committee compiling a cohesive budget, and Town Meeting approving that budget. When constituents from my precinct have questions about how to get help with something from the town, I know which boards or committees or town departments they should reach out to. I also have a better understanding of the current constraints and opportunities faced by our town across multiple areas.

When I started working with Paul Schlictman on advocating for extending the Red Line further into Arlington, I reached out to the members of my Civic Academy class to see if they were also interested, and several of them were incredibly generous with their time and helped us set up our website and mailing list. I would highly recommend applying to Civic Academy, and I’m very thankful that the town puts so much effort into making it a great experience.

Minneapolis is the most recent governmental entity to disrupt the almost 110 year old idea of local zoning in America by overriding single family zoning. Zoning was developed in the the early 1900’s to control property rights and, in part, to limit access to housing by race. These early laws were upheld by the courts in the 1930’s and the use of zoning to control private property for the interests of the majority became common. Houston Texas did not adopt zoning, an outlier in the nation.

But recently governments are rethinking zoning in light of evidence of exclusionary practices including racism and inadequate supplies of affordable housing. In July Oregon’s legislature voted to essentially ban single family zoning in the state.

Most recently, in the end of July, Minneapolis became the first city this century to remove single family zoning, allowing two family housing units to enter any single family zone as of right. According to the Bloomberg News article, the city took action to remedy the untenable price increases do to single family homes taking a disproportionate amount of city land and services. They hope a wider range of housing, and more housing, will reduce housing costs in the future.

Read the full story from Bloomberg News.

(This post was originally an email message, discussion open space changes proposed by an Affordable Housing article during the Arlington, MA’s 2019 town meeting. It’s also a decent description of our town’s open space laws.)

Sorry this turned out to be a long post. Our open space laws are kind of complicated.

Arlington regulates open space as a percentage of gross floor area, rather than as a percentage of lot area. Let me give a concrete example: say we have a-one story structure with no basement. It covers a certain percentage of the lot area, and has an open space requirement based on the gross floor area (i.e., the interior square footage of the building).

Now, suppose we want to turn this into a two- or three-story structure. The building footprint does not change, and it covers exactly the same percentage of the lot area. However, the open space requirements double (if you’re doing a two-story building), or triple (if you’re doing a three story building). If that quantity of open space isn’t on the lot, then you can’t add the stories.

For this reason, I’d argue that our open space regulations are primarily oriented to limiting the size of buildings. You really can’t allow more density (or taller buildings) without reducing the open space requirements. Alternatively, if the requirements were based on a percentage of lot area, we probably wouldn’t need a reduction. (Cambridge’s equivalent is “Private Open Space”, and they regulate it as a percentage of lot area.)

The other weird thing about our open space laws is that we define “usable open space” in such a way that it’s possible to have none. (Usable open space must have a minimum horizontal dimension of 25′, a grade of 8% or less, and be free of parking and vehicular traffic). I live on a nonconforming lot that does not meet these requirements, as do the majority of homes in my neighborhood.

Suppose I wanted to build an addition, which would increase the gross floor area. With the non-conformity, I’d have to go in front of the ZBA and show that the current lot has 0% usable open space, and that the house + addition produces a lot with 0% usable open space. Because 0% = 0%, I have not increased the nonconformity, and would be able to build the addition, provided that all of the other dimensional constraints of the bylaw are satisified. Although this isn’t directly related to Article 16, it’s an amusing side effect of how the bylaw is written.

Finally, roofs and balconies. Section 5.3.19 of our current ZBL allows usable open space on balconies at least six feet wide, and on roofs that are no more than 10′ above the lowest occupied floor. We allow 50% of usable open space requirements to be satisfied in this manner.

The relevant section of Article 16 would create a 8.2.4(C)(1) which includes the language

Up to 25% of the landscaped open space may include balconies at least 5 feet by 8 feet in size only accessible through a dwelling unit and developed for the use of the occupant of such dwelling unit.

Article 16’s incentive bonuses strike the usable open space requirement, and double the landscaped open space requirement. With only landscaped open space, 5.3.19 doesn’t apply (it only pertains to usable open space). The language I’ve quoted adds something 5.3.19-like, but for landscaped open space. I say 5.3.19-like because it has a 25% cap rather than a 50% cap, and requires eligible balconies to be at least 5’x8′, rather than 6′ wide.

Here are a few pieces of supporting documentation:

- definitions of landscaped and usable open space from our ZBL

- a diagram to illustrate the difference between landscaped and usable open space.

- The text of section 5.3.19 (which is referenced by the diagram)

- the main motion for Article 16

The calculation for what is permanently affordable housing is complicated. Arlington’s affordable rate is based on a region that includes the Area Median Income (AMI) of the Cambridge-Boston-Quincy region. The rate is adjusted and reset periodically according to federal HUD guidelines. The rate is applied based on family size and on the Town’s definition of what income level is eligible for Inclusionary Housing opportunities in Arlington. In Arlington a 3 person family would qualify if their income was under 60% of AMI. At this time, that is approximately $58,000 for a family of three.

For more information, see this table of income limits from Cambridge’s Community Development Department, and this short paper on affordable housing from the City of Boston.

Accessory Dwelling Units (aka “granny flats”)

The following information was presented to the Arlington Redevelopment Board in October, 2020 by Barbara Thornton, TMM, Precinct 16

This Article proposes to allow Accessory Dwelling Units, “as of right”, in each of the 8 residential zoning districts in Arlington.

Why is this zoning legislation important?

Arlington is increasingly losing the diversity it once had. It has become increasingly difficult for residents who have grown up and grown old in the town to remain here. This will only become more difficult as the effects of tax increases to support the new schools, including the high school, roll into the tax bills for lower income residents and senior citizens on a fixed income. For young adults raised in Arlington, the price of a home to buy or to rent is increasingly out of reach.

Who benefits from ADUs?

- Families benefit from greater flexibility as their needs change over time and, in particular providing options for older adults to be able to stay in their homes and for households with disabled persons or young adults who want additional privacy but still be within a family setting.

- Residents seeking an increase in the diversity of housing choices in the Town while respecting the residential character and scale of existing neighborhoods; ADUs provide a non-subsidized form of housing that is generally less costly and more affordable than similar units in multifamily buildings;

- Residents wanting more housing units in Arlington’s total housing stock with minimal adverse effects on Arlington’s neighborhoods.

What authority and established policy is this built on?

Arlington’s Master Plan is the foundational document establishing the validity and mission for pursuing the zoning change that will allow Accessory Dwelling Units.

Under Introduction in Part 5, Housing and Residential Development, the Master Plan states: Arlington’s Master Plan provides a framework for addressing key issues such as affordability, transit-oriented residential development, and aging in place.

The Master Plan states that the American Community Survey (ACS) reports that Arlington’s housing units are slightly larger than those in other inner-suburbs and small cities. In Arlington, the median number of rooms per unit is 5.7. There is a great deal of difference in density and housing size among the different Arlington neighborhoods. The generally larger size of homes makes it easier to contemplate a successful move to encourage ADUs.

What do other municipalities do?

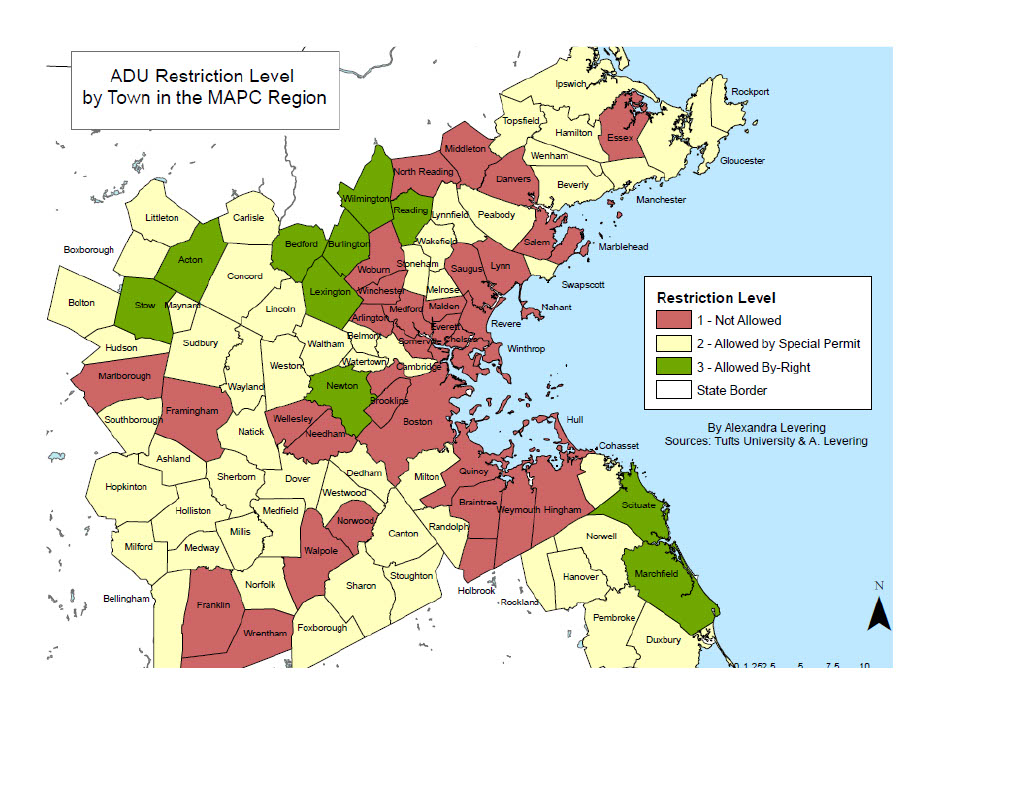

According to a study (https://equitable-arlington.org/2020/02/16/accessory-dwelling-units-policies/), by 2017 65 out of 101 municipalities in the greater Boston (MAPC) region allowed Accessory Dwelling Units by right or by special permit. The average number of ADU’s added per year was only about 3. But by 2017, Lexington had 75 ADUs and Newton had 73. Both of these communities were among about 10 “as of right” municipalities in the MAPC region. This finding suggests that communities with more restrictions are less likely to see any significant affordable housing benefits.

Even in the midst of a housing crisis in this region, according to Amy Dain, housing expert, (https://equitable-arlington.org/2020/02/18/zoning-for-accessory-dwelling-units/) most municipalities still have zoning laws that restrict single family home owners from creating more affordable housing.

And this is despite the fact that, as according to Banker & Tradesman, March 10, 2020: https://www.bankerandtradesman.com/63-percent-in-greater-boston-back-adus/, 63% of people in the region approve of ADUs. California has recently passed strong pro-ADU legislation. A study by Zillow further corroborated this strong interest in communities across the US, including our region. https://equitable-arlington.org/2020/03/10/adu-popularity/.

Learn more about Accessory Dwelling Units/ “Granny Flats” here: https://planning.org/knowledgebase/accessorydwellings/

Why Is This Our Issue & What Should We Do About It?

(presented by Adam Chapdelaine, Town Manager, to Select Board on July 22, 2019)

Overview

Since 1980 the price of housing in Massachusetts has surged well ahead of other fast growing states including California and New York. While the national “House Price Index” is just below 400, four times what an average house might have cost in 1980, a typical house in Massachusetts is now about 720% what it was in 1980. Median household income in the state has only increased about 15% during the same period. No wonder people in Arlington are feeling the stresses of housing costs if they want to live here and are feeling protective of the equity value time has provided them if they bought years ago.

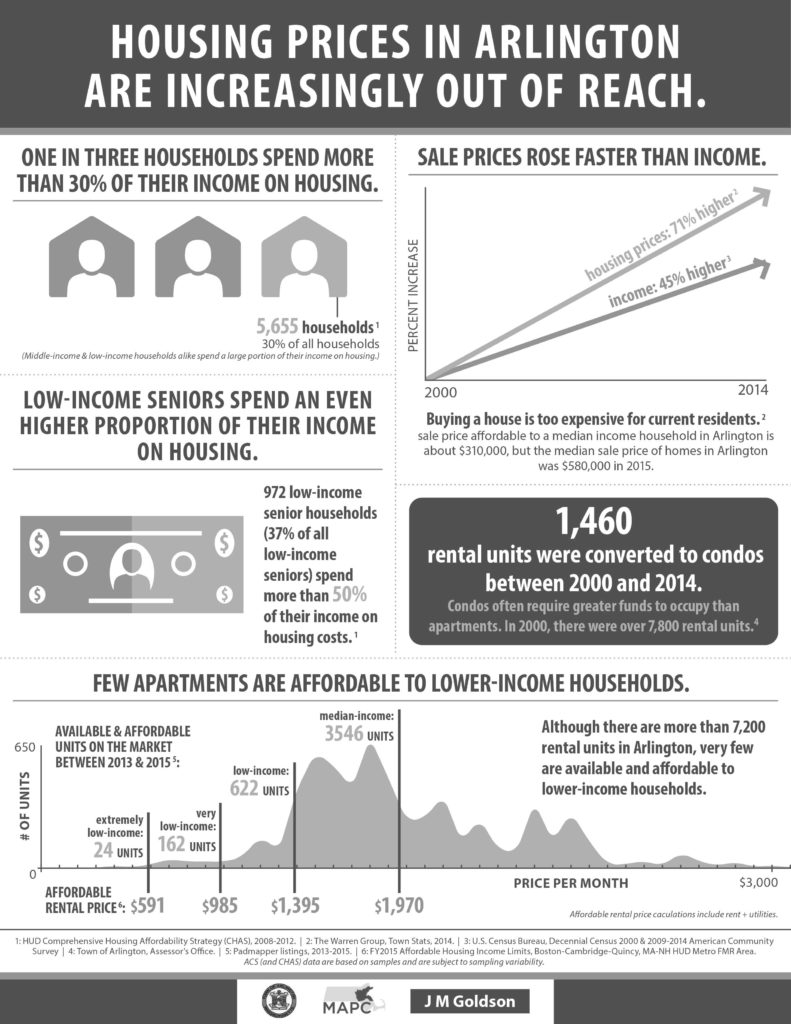

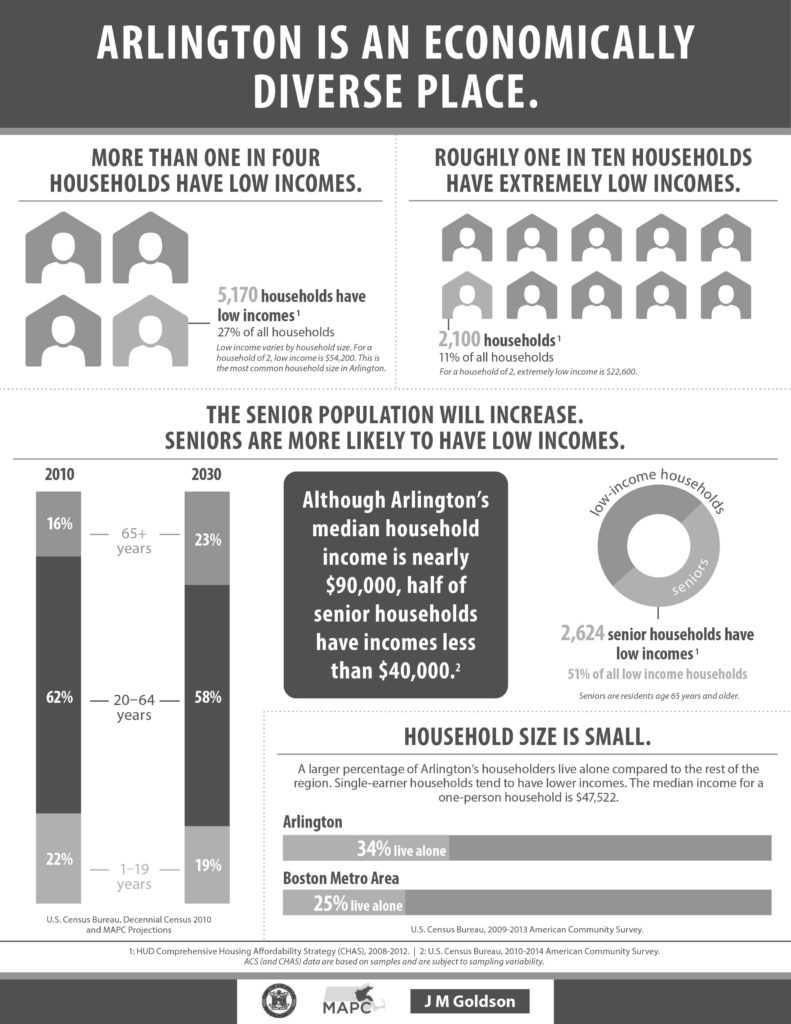

In response to concerns about zoning, affordable housing and housing density, the Town joined the “Mayors’ (and Managers’) Coalition on Housing” to address these growing pressures. This 12 page slide deck presentation outlines the key data points, the number of low and very low income households in Arlington, the rate of condo conversion that is absorbing rental units, etc.

Solutions are offered including:

• Amendments to Inclusionary Zoning Bylaw

• Housing Creation Along Commercial Corridor – Mixed Use & Zoning Along Corridor

• Accessory Dwelling Units – Potential Age & Family Restrictions

• Other Tools Can Be Considered That Are Outside of Zoning But Have An Impact on Housing

Chapdelaine’s suggested next steps are:

• Continued Public Engagement

• Town Manager & Director of DPCD Meet with ARB

• Select Board & ARB Hold Joint Meeting in Early Fall

• ARB Recommends Strategies to Pursue in Late Fall/Early Winter

The Select Board approved the suggested next steps and a joint ARB/ Select Board meeting should be scheduled in the near future.

Note from Reporter: As a community, Arlington has long prided itself on its economic diversity. With condo conversions, tear downs leading to “McMansions”, higher paid workers arriving in response to new jobs, etc., Arlington is at great risk of losing this diversity that has long enriched the community. Retirees looking to downsize and young people who have grown up in Arlington looking for their first apartment are finding it impossible to stay in town. Shop keepers and town employees are challenged to afford the rising housing costs. With a reconsideration of zoning along Arlington’s transit corridors, Arlington NOW has an opportunity to create new village centers, like those recommended in the recent STATE OF HOUSING report. These village centers along our transit corridors could be higher, denser but also offer the compelling visual design and amenities desired by people who want to walk to cafes, shops and public transit.