In 2015 Town Meeting approved the Master Plan. Following is the Housing chapter of that plan. It contains a great deal of information about details of the housing situation in Arlington, challenges of housing price increases, needs for specialty housing, opportunities for meeting these needs, etc. The authors found that “most cities and towns around Arlington experienced a significant rise in housing values from 2000 to 2010. A 40 percent increase in the median value was fairly common. However, Arlington experienced more dramatic growth in housing values than any community in the immediate area, except Somerville. In fact, Arlington’s home values almost doubled.” This and related data helps explain why the need for affordable housing is now so acute.

Related articles

(This post originally appeared as a one-page handout, distributed at The State of Zoning for Multi-Family Housing in Greater Boston.)

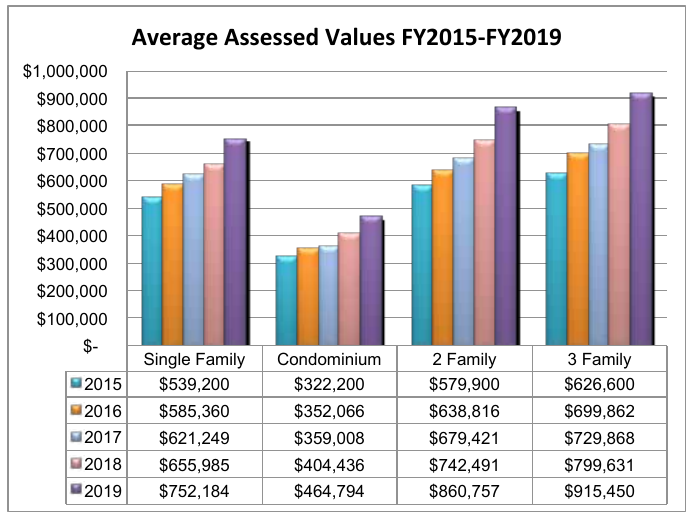

This chart shows the assessed value of Arlington’s low density housing from 2015–2019 (assessed values generally reflect market values from two years prior). During this time, home values increased between 39% (single-family homes) and 48% (two-family homes). Most of the change comes from the increasing cost of land. As a point of comparison, the US experienced 7.7% inflation during the same period. (1)

Arlington has constructed six apartment buildings in the 44 years since the town’s zoning bylaw was rewritten in 1975; we constructed 75 of them in the preceding 44 years.(2) Like numerous communities in the Metro-Boston area, we’re experiencing a high demand for housing, but our zoning regulations have created a paper wall that prevents more housing — including affordable housing — from being built.

Communities need adequate housing, but they also need housing diversity: different types of housing at different price points. The housing needs of young adults are different than the housing needs of parents with children, which are in turn different than the housing needs of senior citizens. As demographics change, housing needs change too. Keeping people in town means providing them with the opportunity to upsize or downsize when the need arises.

If Arlington’s housing costs had only increased with the rate of inflation, the cost of single family housing would average $581K, over $170K less than today. The median household income in Arlington is about $103K/year.(3) Buying an average single family-home with that income on a typical 30-year mortgage would require approximately 46% of a household’s monthly income.(4)

Either homes in Arlington will only be available to people who have much more substantial incomes than current residents, or the town will find a way to balance the rapidly growing cost of land against the housing needs of its current citizens, those still in school, those preparing to downsize as well as those looking for a bigger space.

In addition, Arlington’s commercial economy will thrive with a greater number of housing units so we can keep the empty nesters, and the new college graduates who have lived in the town for years, as well as welcome new Arlingtonians to support our local businesses, restaurants and other services.

Our Town, like others in the state, is looking for ways to balance the needs of our citizens with the market forces of rising land costs while maintaining a healthy, diverse community.

Footnotes

- The inflation amount comes from Inflation amount from https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

- Figures on multi-family unit construction are taken from Arlington Assessor’s data. They reflect multi-family buildings that are still used as rental apartments.

- Income levels come from 2013-2017 ACS 5-year data for Arlington, MA.

- Assuming 10% downpayment, 4% interest, $800/year for insurance, and Arlington’s $11.26 tax rate, the monthly mortgage payment would be nearly $4000/month.

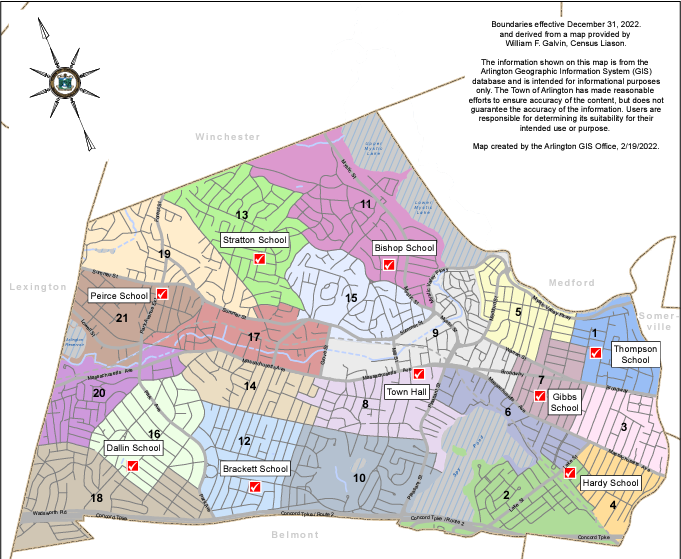

You may not know who your Town Meeting Members are. You may not even know what precinct you live in. We’re here to help!

What’s My Precinct?

This PDF map of Arlington is divided by precinct. You may need to zoom in to see your precinct.

Who Are My Town Meeting Members?

The town of Arlington has a public list of town meeting members and their contact information. Send them an email telling them how you feel, or ask them if you can take a walk and discuss the MBTA Communities Plan.

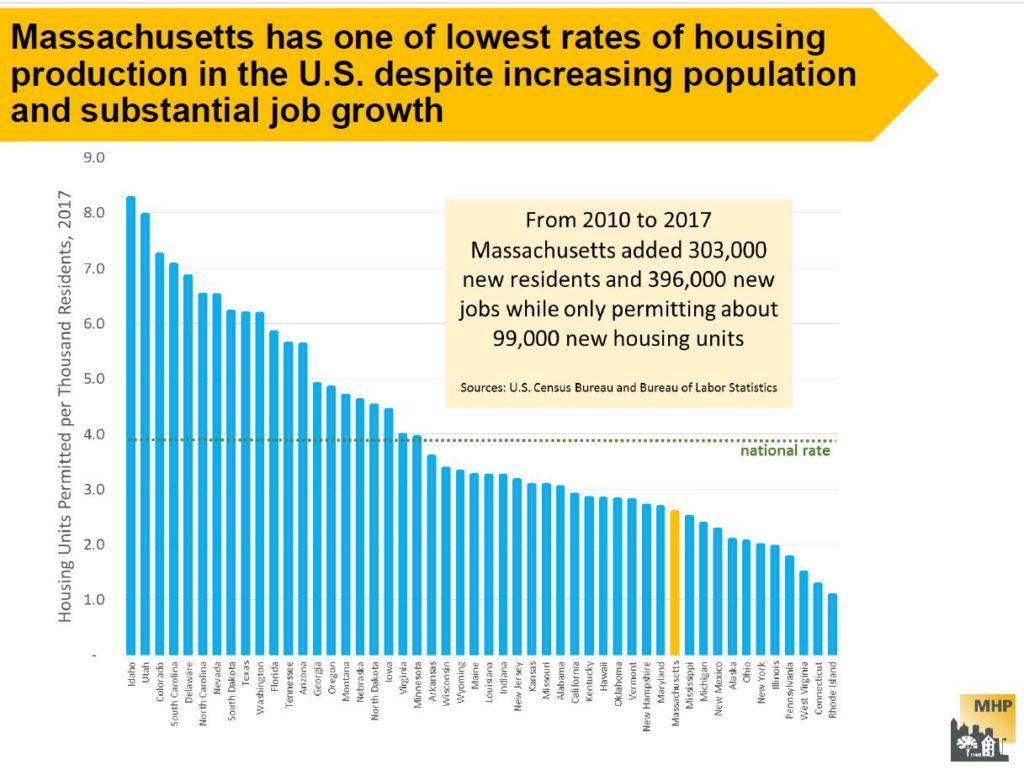

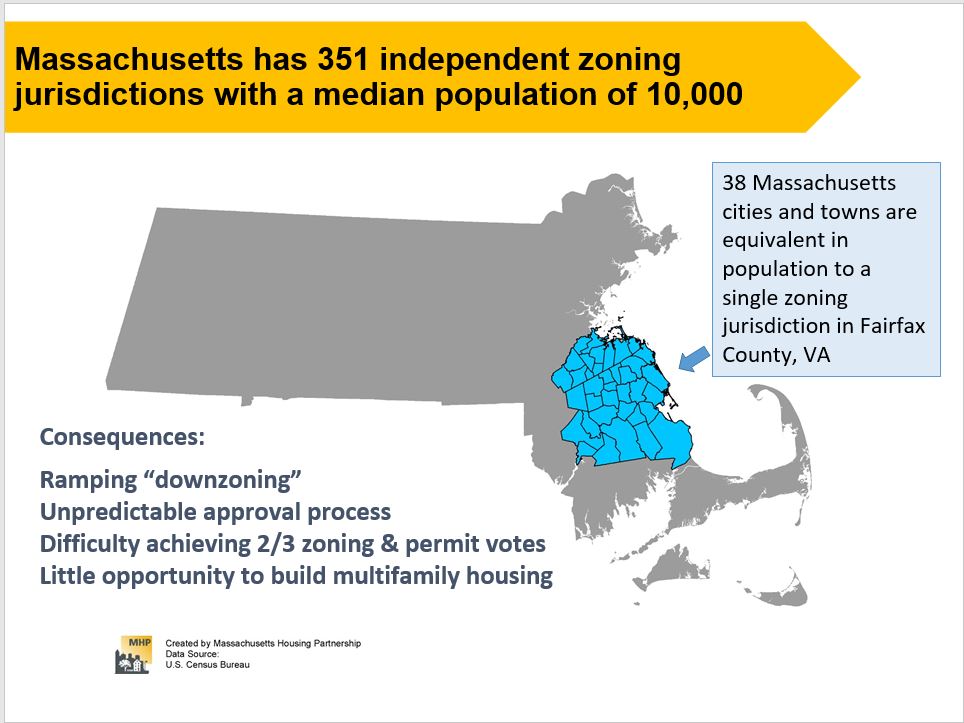

Data in a Mass Housing Partnership report shows how far behind the Boston metropolitan area has fallen in meeting the housing needs of its citizens. There are four primary categories for measuring the inadequacies: 1. Availability, 2. Affordability, 3. L0cation and Mobility and 4. Equitability. See the full report for more data and examples. Two slides are shown below.

As the public hearings on the zoning articles proceeded in late winter and early spring, 2019, it became clear that there was a very strong sentiment that the proposed increase in density in these designated zoning districts should result in an increase in affordable housing in Arlington. This coincided with the approved 2015 Master Plan’s stated goals:

- Encourage mixed-use development that includes affordable housing, primarily in well-established commercial areas.

- Provide a variety of housing options for a range of incomes, ages, family sizes, and needs.

- Preserve the “streetcar suburb” character of Arlington’s residential neighborhoods.

- Encourage sustainable construction and renovation of new and existing structures (see ch. 5, pg 77++ for housing section)

- The Yes on 16 report supports the citizen initiated petition resulting in Article 16 and demonstrates the tremendous impact of rapidly increasing land values on the overall affordability of property in Arlington. Building a stack of homes on one footprint is far more financially affordable than creating a single home on the same footprint of land.

by Alexander vonHoffman, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, February 2006

The case study shows that in the 1970s the Town of Arlington completely abandoned its policy of encouraging development of apartment buildings—and high-rise buildings at that—and adopted requirements that severely constricted the possibilities for developing multifamily dwellings. Although members of the elite introduced the new approach, they were backed by rank-and-file citizens, who took up the cause to protect their neighborhoods from perceived threats.

The report outlines an intentional effort using land use and planning tools like zoning and building approvals, to exclude those with less desirable income or racial characteristics from residing in Arlington. Additional perspectives on Arlington’s exclusionary zoning efforts during this period are reported here.

(Barbara Thornton, Arlington and Roberta Cameron, Medford)

Our communities need more housing that families and individuals can afford. From 2010 to 2017, Greater Boston communities added 245,000 new jobs but only permitted 71,600 new units of housing. Prices are escalating as homebuyers and renters bid up the prices of the limited supply of housing. As a result, one quarter of all renters in Massachusetts now spend more than 50% of their income on housing. (It should be only about 30% of monthly gross income spent on housing costs.) Municipalities have been over-restricting housing development relative to need. The expensive cost of housing not only affects individual households, but also negatively affects neighborhoods and the region as a whole. Lack of affordability limits income diversity in communities. It makes it harder for businesses to recruit employees.

Over the last two years, researcher Amy Dain, commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, has systematically reviewed the bylaws, ordinances, and plans for the 100 cities and towns around Boston to uncover how local zoning affects multifamily housing and why local communities failing to provide enough additional housing to keep the prices from skyrocketing for renters and those who want to purchase homes.

Interested in housing affordability and why the cost of housing is increasing so dramatically to prevent average income residents from affording homes in the 100 municipalities around Boston? Arlington and Medford residents are pleased to welcome author Amy Dain to present her report, THE STATE OF ZONING FOR MULTIFAMILY HOUSING IN GREATER BOSTON (June 2019). Learn more about the so-called “paper wall” restricting production, common trends in local zoning, and best practices to increase production going forward. Learn about efforts in Medford and Arlington to increase housing production and affordable housing and how you can get involved. Thursday, July 25, 2019, 7:00 PM at the Medford Housing Authority, Saltonstall Building, 121 Riverside Avenue, Medford. (Parking is available.)

To access the full report, go to: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

The Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, which commissioned the study, provides the following summary of the four principal findings and takeaways:

1) Very little land is zoned for multi-family housing.

For the most part, local zoning keeps new multi-family housing out of existing residential neighborhoods, which cover the majority of the region’s land area.

In addition, cities and towns highly restrict the density of land that is zoned for multi-family use via height limitations, setbacks, and dwelling units per acre. Many of the multi-family zones have already been built out to allowable densities, which mean that although multi-family housing is on the books, it does not exist in practice.

At least a third of the municipalities have virtually no multi-family zoning or plan for growth.

Takeaway: We need to allow concentrated density in multi-family zoning districts that are in sensible locations and allow for incremental growth over a larger area.

2) We are moving to a system of project-by-project decision-making.

Unlike much of the rest of the country, Massachusetts does not require communities to update their zoning on a regular basis and make it consistent with local plans. Although state law ostensibly requires municipalities to update their master plans every ten years, the state does not enforce this provision and most communities lack up-to-date plans.

Instead, the research documents a trend away from predictable zoning districts and toward “floating districts,” project-by-project decision-making, and discretionary permits. Dain found that 57% of multi-family units approved in the region from 2015-2017 were approved by special permit, 22% by 40B (including “friendly” 40B projects), 7% by use variance, and only 14% by “as-of-right” zoning.

There also seems to be a trend toward politicizing development decisions by shifting special permit granting authority to City Council and town meeting. The system emphasizes ad hoc negotiation, which in some cases can achieve a more beneficial project. Yet the overall outcome is a slower, more expensive development process that produces fewer units. Approving projects one by one inhibits the critical infrastructure planning and investments needed to support the growth of an entire district.

Takeaway: We would be better served by a system that retains the benefits of flexibility while offering more speed and predictability.

3) The most widespread trend in zoning for multi-family housing has been to adopt mixed-use zoning.

83 of out of 100 municipalities have adopted some form of mixed-use zoning, most in the last two decades. There is a growing understanding that many people, both old and young, prefer to live in vibrant downtowns, town centers and villages, where they can easily walk to some of the amenities that they want. Malls, plazas and retail areas are increasingly incorporating housing and becoming lifestyle centers.

Yet with few exceptions, the approach to allowing housing in these areas has been cautious and incremental. These projects are only meeting a small portion of the region’s need for housing and often take many years of planning to realize. In addition, the challenges facing the retail sector can make a successful mixed-use strategy problematic. Commercial development tends to meet less opposition than residential development, even in mixed-use areas.

Takeaway: We need more multi-family housing in and around mixed-use hubs, but not require every project to be mixed-use itself.

4) Despite their efforts, communities continue to build much more new housing on their outskirts rather than in their town centers and downtowns.

About half of the communities in the study permitted some infill housing units in their historic centers, but her case studies show that these infill projects are modest in scale and can take up to 15 years to plan and permit.

On the other hand, many more units are getting built in less-developed areas with fewer abutters. This includes conversion of former industrial properties, office parks, and other parcels disconnected from the rest of the community by highways, train tracks, waterways or other barriers. This much-needed housing can be isolated even when dense, and still car-dependent because of limited access to public transportation and lack of walkability.

Takeaway: We need to allow more housing in historic centers as well as incremental growth around those centers. Furthermore, we need to plan an integrated approach to growth districts so that they can be better connected to the community and the region.

Interview with Aaron Clausen, AICP; City of Beverly, Director, Planning and Community Development

Rather than express generalized worry about the “lack of affordable housing”, Peabody, Salem and Beverly have created an intermunicipal Memorandum of Mnderstanding (MOU) to very specifically define and target the problem and the population they want to address.

According to Aaron Clausen, “There is a fair amount of context that goes along with the MOU, but primarily the communities got together as sort of a coalition to survey and understand what was going on relative to homelessness. What came out of that is a recognition that there is not enough affordable housing generally, and particularly transitional housing, or more specifically permanent supportive housing.

“Salem and Beverly both have shelters, however the shelters were basically serving as permanent housing (and running out of space). That won’t help someone into a stable housing situation. Anyway, this was the agreement (attached MOU) and the good news is that it has resulted in affordable housing projects; one is done in Salem for individuals and Beverly has a 75 unit family housing project permitted and seeking funding that has a set aside for families either homeless or in danger of becoming homeless.

“There is also a redevelopment of a YMCA in downtown Beverly that will increase the number of Single Room Occupancy units. I wouldn’t say that the MOU got it done by itself but it helps demonstrate a regional approach. ”

To see the actual Memorandum of Understanding between these three municipalities to address affordable housing, particularly for people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, click HERE.

Minneapolis is the most recent governmental entity to disrupt the almost 110 year old idea of local zoning in America by overriding single family zoning. Zoning was developed in the the early 1900’s to control property rights and, in part, to limit access to housing by race. These early laws were upheld by the courts in the 1930’s and the use of zoning to control private property for the interests of the majority became common. Houston Texas did not adopt zoning, an outlier in the nation.

But recently governments are rethinking zoning in light of evidence of exclusionary practices including racism and inadequate supplies of affordable housing. In July Oregon’s legislature voted to essentially ban single family zoning in the state.

Most recently, in the end of July, Minneapolis became the first city this century to remove single family zoning, allowing two family housing units to enter any single family zone as of right. According to the Bloomberg News article, the city took action to remedy the untenable price increases do to single family homes taking a disproportionate amount of city land and services. They hope a wider range of housing, and more housing, will reduce housing costs in the future.

Read the full story from Bloomberg News.