The new proposal is just the most recent step in a process that reaches back almost a decade, culminating in the Master Plan (2015), the Housing Production Plan (2016) and the mixed-using zoning amendments of 2016. The Town has consistently proposed smart growth: more development along Arlington’s transit corridors to increase the tax base, stimulate local commerce, and provide more varied housing opportunities for everyone, including low and moderate income Arlingtonians. This year’s proposals are no head-long rush into change. Today’s debate is similar to the debate before Town Meeting three years ago. If anything, progress has been frustratingly slow. To realize the Master Plan’s vision of a vibrant Arlington with diverse housing types for a diverse population, we must stay the course on which we have been embarked for so long.

Related articles

It’s the time of year when folks in Arlington are taking out nomination papers, gathering signatures, and strategizing on how to campaign for the town election on Saturday April 1st. The town election is where we choose members of Arlington’s governing institutions, including the Select Board (Arlington’s executive branch), the School Committee, and — most relevantly for this post — Town Meeting.

If you’re new to New England, Town Meeting is an institution you may not have heard of, but it’s basically the town’s Legislative Branch. Town Meeting consists of 12 members from each of 21 Precincts, for 252 members total. Members serve three-year terms, with one-third of the seats up for election in any year, so that each precinct elects four representatives per year (perhaps with an extra seat or two, as needed to fill vacancies). For a deeper dive, Envision Arlington’s ABC’s of Arlington Government gives a great overview of Arlington’s government structure.

As our legislative branch, town meeting’s powers and responsibilities include:

- Passing the Town’s Operating Budget, which details planned expenses for the next year.

- Approving the town’s Capital Budget, which includes vehicle and equipment purchases, playgrounds, and town facilities.

- Bylaw changes. Town meeting is the only body that can amend the towns bylaws, including ones that affect housing — what kinds can be built, how much, and where.

Town Meeting is an excellent opportunity to serve your community, and to learn about how Arlington and its municipal government works. Any registered voter is eligible to run. If this sounds like an interesting prospect, we encourage you to run! Here’s what you’ll need to do:

- Have a look at the town’s Information for new and Prospective Town Meeting Members.

- Contact the Town Clerk’s office to get a set of nomination papers. You’ll need to do this by 5:00 PM February 12th, 2025 at the latest.

- Gather signatures. You’ll need signatures from at least ten registered voters in your precinct to get on the ballot (it’s always good to get a few extra signatures, to be safe).

- Return your signed nomination papers to the Clerk’s office by February 14, 2025 at 5:00 PM.

- Campaign! Get a map and voter list for your precinct, knock on doors, and introduce yourself. (Having a flier to distribute is also helpful.)

- Vote on Saturday April 5th, and wait for the results.

Town Meeting traditionally meets every Monday and Wednesday at 8:00 PM, starting on the 4th Monday in April (which is April 28th this year), and lasting until the year’s business is concluded (typically a few weeks).

If you’d like to connect with an experienced Town Meeting Member about the logistics of campaigning, or the reality of serving at Town Meeting, please email info(AT)equitable-arlington.org and we’d be happy to make an introduction.

During the past few years, Town Meeting was our pathway to legalizing accessory dwelling units, reducing minimum parking requirements, loosening restrictions on mixed-use development in Arlington’s business districts, and adopting multi-family zoning for MBTA Communities. Aside from being a rewarding experience, it’s a way to make a difference!

Prepared by: Barbara Thornton with the capable assistance of Alex Bagnall, Pamela Hallett, Patrick Hanlon, Karen Kelleher, Steve Revilak and Jennifer Susse.

As Arlington considers new zoning and other policy decisions to increase the amount of affordable housing in the town, a concern has been raised about the threat of greater costs to the Town’s budget from new people with school age children moving into the town. The concern: additional children in the public schools costs the town more than the additional new property tax revenue the Town collects from the new housing.

This post examines this concern, drawing on data from two recent housing developments, representing 283 units of housing in Arlington, to determine that actually the Town budget gains over 4.5 times the actual cost of paying for the students. According to the most recent 2020 tax bills, the Town expects to collect $1,250,370 in revenue and to spend an additional $269,589 for the new Arlington Public School students living in these developments.

The data suggests that the fear of increased school costs, overwhelming the potential new revenue from new housing construction is not warranted.

For more information, see the full post here.

Article 1 in a series on the Arlington, MA master planning process. Prepared by Barbara Thornton

Arlington, located about 15 miles north west of Boston, is now developing a master plan that will reflect the visions and expectations of the community and will provide enabling steps for the community to move toward this vision over the next decade or two. Initial studies have been done, public meetings have been held. The Town will begin in January 2015 to pull together the vision for its future as written in a new Master Plan.

In developing a new master plan, the Town of Arlington follows in the footsteps laid down thousands of years ago when Greeks, Romans and other civilizations determined the best layout for a city before they started to build. In more recent times, William Penn laid out his utopian view of Philadelphia with a gridiron street pattern and public squares in 1682. Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant developed the hub and spoke street plan for Washington DC in 1798. City planning started with new cities, relatively empty land and a “master builder” typically an architect, engineer or landscape architect commissioned by the land holders to develop a visionary design.

In the 1900’s era of Progressive government in America, citizens sought ways to reach a consensus on how their existing cities should evolve. State and federal laws passed to help guide this process, seeing land use decisions as more than just a private landowner’s right but rather a process that involved improving the health and wellbeing of the entire community. While the focus on master planning was and still is primarily physical, 21st century master planners are typically convened by the local municipality, work with the help of trained planners and architects and rely heavily on the knowledge and participation of their citizenry to reflect a future vision of the health and wellbeing of the community. This vision is crafted into a Master Plan. In Arlington the process is guided by Carol Kowalski, Director of Planning and Community Development, with professional support from RKG Associates, a company of planners and architects and with the vision of the Master Planning advisory committee, co-chaired by Carol Svenson and Charles Kalauskas, Arlington residents, and by the citizens who share their concerns and hopes with the process as it evolves. This happens through public meetings, letters, email, and surveys. The most recent survey asks residents to respond on transportation modes and commuting patterns

We all do planning. Starting a family, a business or a career, we lay out our goals and assume the steps necessary to accomplish these goals and we periodically revise them as necessary. The same thing is true for cities. Based on changes in population, economic development, etc. cities, from time to time, need to revise their plans. In Massachusetts the enabling acts for planning and zoning are here http://www.mass.gov/hed/community/planning/zoning-resources.html. The specific law for Massachusetts is MGL Ch. 41 sect. 81D. This plan, whether called a city plan, master plan, general plan, comprehensive plan or development plan, has some constant characteristics independent of the specific municipality: focus on the built environment, long range view (10-20 years), covers the entire municipality, reflects the municipality’s vision of its future, and how this future is to be achieved. Typically it is broken out into a number of chapters or “elements” reflecting the situation as it is, the data showing the potential opportunities and concerns and recommendations for how to maximize the desired opportunities and minimize the concerns for each element.

Since beginning the master planning process in October, 2012, Arlington has had a number of community meetings (see http://vod.acmi.tv/category/government/arlingtons-master-plan/ ) gathering ideas from citizens, sharing data collected by planners and architects and moving toward a sense of what the future of Arlington should look like. The major elements of Arlington’s plan include these elements:

1. Visions and Goals http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19829

2. Demographic Characteristics http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19838

3. Land Use http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19834

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19825

4. Transportation http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19830

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19822

5. Economic Development http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19837

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19828

6. Housing http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19835

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19826

7. Open Space and Recreation http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19832

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19824

8. Historic and Cultural Resources http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19836

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19827

9. Public Facilities and Services http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19831

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19823

10. Natural Resources

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19824

The upcoming articles in this series will focus on each individual element in the Town of Arlington’s Master Plan.

(This post originally appeared as a one-page handout, distributed at The State of Zoning for Multi-Family Housing in Greater Boston.)

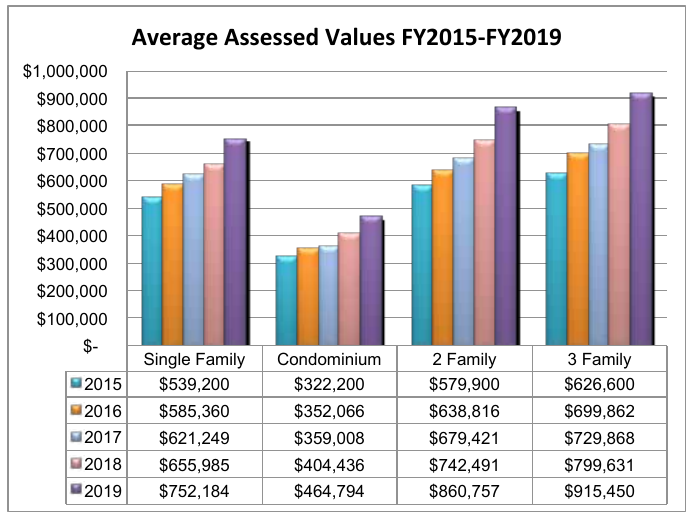

This chart shows the assessed value of Arlington’s low density housing from 2015–2019 (assessed values generally reflect market values from two years prior). During this time, home values increased between 39% (single-family homes) and 48% (two-family homes). Most of the change comes from the increasing cost of land. As a point of comparison, the US experienced 7.7% inflation during the same period. (1)

Arlington has constructed six apartment buildings in the 44 years since the town’s zoning bylaw was rewritten in 1975; we constructed 75 of them in the preceding 44 years.(2) Like numerous communities in the Metro-Boston area, we’re experiencing a high demand for housing, but our zoning regulations have created a paper wall that prevents more housing — including affordable housing — from being built.

Communities need adequate housing, but they also need housing diversity: different types of housing at different price points. The housing needs of young adults are different than the housing needs of parents with children, which are in turn different than the housing needs of senior citizens. As demographics change, housing needs change too. Keeping people in town means providing them with the opportunity to upsize or downsize when the need arises.

If Arlington’s housing costs had only increased with the rate of inflation, the cost of single family housing would average $581K, over $170K less than today. The median household income in Arlington is about $103K/year.(3) Buying an average single family-home with that income on a typical 30-year mortgage would require approximately 46% of a household’s monthly income.(4)

Either homes in Arlington will only be available to people who have much more substantial incomes than current residents, or the town will find a way to balance the rapidly growing cost of land against the housing needs of its current citizens, those still in school, those preparing to downsize as well as those looking for a bigger space.

In addition, Arlington’s commercial economy will thrive with a greater number of housing units so we can keep the empty nesters, and the new college graduates who have lived in the town for years, as well as welcome new Arlingtonians to support our local businesses, restaurants and other services.

Our Town, like others in the state, is looking for ways to balance the needs of our citizens with the market forces of rising land costs while maintaining a healthy, diverse community.

Footnotes

- The inflation amount comes from Inflation amount from https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

- Figures on multi-family unit construction are taken from Arlington Assessor’s data. They reflect multi-family buildings that are still used as rental apartments.

- Income levels come from 2013-2017 ACS 5-year data for Arlington, MA.

- Assuming 10% downpayment, 4% interest, $800/year for insurance, and Arlington’s $11.26 tax rate, the monthly mortgage payment would be nearly $4000/month.

The City of Somerville estimates that a 2% real estate transfer fee — with 1% paid by sellers and 1% paid by buyers, and that exempts owner-occupants (defined as persons residing in the property for at least two years) — could generate up to $6 million per year for affordable housing. The hotter the market, and the greater the number of property transactions, the more such a fee would generate.

Other municipalities are also looking at this legislation but need “home rule” permission, one municipality at a time, from the state to enact it locally. Or, alternatively, legislation could be passed at the state level to allow all municipalities to opt into such a program and design their own terms. This would be much like the well regarded Community Preservation Act (CPA) program that provides funds for local governments to do historic preservation, conservation, etc.

This memorandum from the City of Somerville to the legislature provides a great deal of information on the history, background and justification for such legislation.

House bill 1769, filed January, 2019, is an “Act supporting affordable housing with a local option for a fee to be applied to certain real estate transactions“.

COMMENT:

KK: This article suggests Arlington may be likely to pass a real estate transfer tax: https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/12/19/boston-one-step-closer-to-a-luxury-real-estate-transfer-tax/

(By Vince Baudoin and James Fleming)

Could Arlington be better using its curb space? Here are some ways the curb can be used to create green infrastructure, promote public safety and accessibility, support sustainable transportation, strengthen business districts, and enable new ‘car-light’ development.

Roughly six inches high and made of concrete or granite, the curb marks the edge of the roadway, channels runoff, protects the sidewalk, and gathers stray leaves. When not assigned any other use, the space in front of the curb it usually serves as free storage for personal automobiles.

Yet the humble curb is a limited resource that can serve the community in many more ways. Have you thought about how your town budgets its curb space? For that matter, has your town thought about how it budgets its curb space?

While Arlington mostly uses its curb space for parking, some areas have other curb uses designed to achieve a specific goal. Consider the streets you use often. Have you seen an unsolved problem, or a missed opportunity, that a different use of the curb could help solve?

Create green infrastructure

The Town has miles of paved roadway. When it rains or snows, water runs into storm drains, carrying salt, oil, and other pollutants with it. The storm drains dump these pollutants directly into long-degraded waterways such as the Mill Brook, Alewife Brook, and the Mystic River. The Public Works department struggles to keep grates clear and drains from overflowing.

One solution: Use the curb for more greenery! The curb can be extended to create a rain garden or tree planting strip. The rain garden helps slow runoff and filter the water before it enters the drain, while trees benefit from additional room for the roots to grow without damaging the sidewalk. A side benefit: narrowing the street encourages drivers to slow down, making neighborhoods safer.

Promote public safety and accessibility

Often, portions of the curb are set aside for public safety purposes. For example, a fire lane provides fire department access to key buildings, such as the high school, shown below. Fire hydrants also enjoy special curb status.

Other times, no-parking zones are established to enhance the free flow of traffic, such as here at Broadway Plaza:

Where pedestrian crosswalks are present, a curb extension is a key safety enhancement. By narrowing the roadway, the curb extension encourages drivers to slow down and look for pedestrians. For pedestrians, it reduces the distance they must cross and prevents cars from parking directly next to the crosswalk and blocking visibility.

Finally, accessible parking spaces can be created along the curb. Arlington has at least 50 designated permit-only on-street parking spaces that provide convenient parking for residents with mobility issues or other disabilities.

Support sustainable transportation

When the curb is mostly used for cars, it is easy to overlook how curbside facilities can enhance other forms of transportation.

In the space of one or two parked cars, this bikeshare station offers space for 11 bikes. However, because it is installed on the roadway, it must be removed every winter so that snow can be cleared. If the curb were extended, the bikeshare station could be used year-round. Another nice feature is bicycle parking: the space to park one car can be used to park six or more bicycles.

A bus stop allows buses to pull to the curb. In some cases, it is appropriate to extend the curb so the bus would stop in the traffic lane; otherwise, it may experience delays when it merges back into traffic.

A bus priority lane provides a dedicated right of way for buses, helping to improve on-time performance. To date, these lanes extend only a few hundred feet into Arlington along Mass Ave. They have proven beneficial in many other communities.

Bike lanes, particularly if they are separated from cars by a physical buffer, greatly enhance the safety and comfort of people traveling on two wheels.

But with a limited roadway width, adding bike lanes is difficult unless the community is flexible enough to consider consolidating curb parking on one side of the street, or moving it to side streets entirely.

Finally, the Town could expand the use of on-street spaces for electric vehicle charging stations, such as this one on Park Ave:

Strengthen business districts

Nowhere is the curb more valuable than in business districts. Businesses thrive when their customers have a convenient way to reach them. Metered parking encourages people to park, do their business, and move along so another patron can take that space. Revenue from parking meters can be spent to improve the business district–for example, by planting flowers and trees.

Metered parking is not the only valuable use of curb space in a business district. Outdoor dining is a way the Town can directly support its restaurants by enabling them to serve additional customers. Here is one example in Arlington Center:

And in Arlington Heights:

Other valuable curb uses in business districts include taxi stands and loading zones. Loading zones in particular are crucial to businesses’ success and help prevent the street from being clogged by early-morning delivery trucks, late-night food-delivery vehicles, and everything in between.

Enable new ‘car-light’ development

With high housing costs and a relatively small commercial tax base, Arlington could benefit from some kinds of development. However, land is valuable and lots are small, so if new buildings are required to have large parking lots, it is very difficult to build new homes and businesses. Plus, large parking lots bring more cars and more traffic. But better curb management can help resolve this dilemma, supporting car-light development that is more sustainable and affordable.

For example, on-street permit parking can enable nearby development with few or no off-street parking spaces. New housing or businesses are a better use of land than parking and will generate more property tax revenue. When parking permits are priced appropriately, they are available to residents who need them but discourage households from adding extra cars they do not need.

Take these hillside houses: access to on-street parking made it possible to build on a steep hillside, where it would have been too expensive and difficult to blast to create off-street parking.

Conclusion

Ask your town leaders if they have a curb management strategy. Is the Town using its limited curb space in support of goals such as green infrastructure, public safety and accessibility, public transportation, local business, and car-light development?

A few days ago, the Boston Globe ran an article titled “2021 set records in Boston Housing Market. What now?“. It’s not unusual to see stories about housing in the news — the market is highly competitive and the sale prices can be jaw dropping. Jaw dropping can take several forms: from the new (and used) homes that sell for over two million dollars, to the amount of money that someone will pay to purchase a small post-war cape (around $900,000, give or take).

According to the globe article, the Greater Boston Association of Realtors estimates that the median price of a single family homes in the Boston area rose 10.5% in 2021, to $750,000. Arlington is comfortably in the upper half of this median: according to our draft housing production plan the median sale price of our single family homes was $862,500 in 2020, and rose to $960,000 in the first half of 2021 (see page 39).

In June 2021, I got myself into a habit of sampling real estate sales listed in the Arlington Advocate, and compiling them into a spreadsheet. My observations are generally consistent with the sources cited above; Arlington’s housing is expensive and it’s appreciated rapidly, particularly in the last 6–10 years. It’s a great time for existing owners, but less so if you’re in the market for your first home.

We’re actually facing two problems, which are related but not identical. The first is high cost, which creates financial stress and a barrier to entry (though it is a boon for those who sell). The second problem is quantity; there are regional and national housing shortages, and that contributes to high prices and bidding wars.

Addressing these challenges will require collective effort on behalf of all communities in the metro area; this is a regional problem and we’ll all have to pitch in. There isn’t a single recipe for what “pitching in” means, but here are some for what communities can do.

First, produce more affordable housing. Affordable housing is a complex regulatory subject, but it basically boils down to two things: (1) the housing is reserved for households with lower incomes than the area as a whole, and (2) there’s a deed restriction (or similar) that prevents it from being sold or rented at market rates. Affordable housing usually costs more to produce than it generates in income, and the difference has to be made up with subsidies. It takes money.

Second, simply produce more housing. This is the obvious way to address an absolute shortage in the number of dwellings available. Some communities have set goals for housing production. Under the Walsh administration, Boston set a goal of producing 69,000 new housing units by 2030. Somerville’s goal is 6000 new housing units, and Cambridge’s is 12,500 (page 152 of pdf). To the best of my knowledge, Arlington has not set a numeric housing production goal, but it’s something I’d like to see us do.

Finally, communities could be more flexible with the types of housing they allow. Arlington is predominantly zoned for single- and two-family homes. The median sale price of our single family homes was $960,000 during the first half of 2021, and a large portion of that comes from the cost of land. That’s the reality we have, and the existing housing costs what it costs. So, we might consider allowing more types of “missing middle” housing, where the per dwelling costs tend to be lower: apartments, town houses, triple-deckers, and the like.

Of course, this assumes that our high cost of housing is a problem that needs to be solved; we could always decide that it isn’t. In the United States, home ownership is seen as a way to build equity and wealth. It’s certainly been fulfilling that objective, especially in recent years.

Article 16 is a proposal to encourage the production of affordable housing in the town of Arlington. I brought this article to town meeting for several reasons, namely, our increasing cost of housing and our increasing cost of land. Arlington is part of the Metropolitan Boston area; we share borders with Cambridge, Somerville, and Medford, and are a mere 5.5 miles from Boston itself. Years ago, people moved out of cities and into the suburbs. That trend has reversed during the last decade, and people are moving back to urban areas, including Metro-Boston. Metro-Boston is a good source of jobs; people come here to work and want to live nearby. That obviously puts pressure on housing prices, and Arlington is not immune from that pressure.

Another reason for proposing Article 16 was my desire to start a conversation about the role our zoning laws play in the cost of housing, and how they might be used to relieve some of that burden. During the 20th century people discovered that one cannot draw a line on a map and say “upper-class households on this side, lower-class households on that side”, but one can draw a line on a map and say “single-family homes on this side, and apartments on that side”. For all practical purposes, the latter achieves the same result as the former. When zoning places a threshold on the cost of housing, it determines who can and cannot afford to live in a given area.

Today 70% of Arlington’s land is exclusively zoned for single family homes, the predominant form of housing in town. In 2013, the median cost of a single-family home was $472,850; this rose to $618,800 in 2018 — an increase of 31%. We can break this down further. The median building cost for a single-family building rose from $226,300 in 2013 to $248,100 in 2018 (an increase of 9.6%), and the median cost for a single-family lot rose from $243,700 to $360,900 (an increase of 48%). Land is a large component of our housing costs, and it continues to rise. Certain neighborhoods (e.g., Kelwyn Manor) saw substantial increases in land assessments in 2019, enough that the Assessor’s office issued a statement to explain the property tax increases. To that end, multifamily housing is a straightforward way to reduce the land costs associated with housing. Putting two units on a lot instead of one decreases the land cost by 50% for each unit.

Article 16 tries to encourage the production of affordable housing (restricted to 60% of the area median income for rentable units and 70% for owner-occupied units). It works as follows:

- Projects of six or more units must make 15% of those units affordable. This is part of our existing bylaws.

- Projects of twenty or more units must make 20% of those units affordable. This is a new provision in Article 16.

- Projects of six or more units that produce more than the required number of affordable units will be eligible for density bonuses, according to the proposed section 8.2.4(C). Essentially, this allows a developer to build a larger building, in exchange for creating more affordable housing.

- Projects of six or more units that produce only the required number of affordable units are not eligible for the density bonuses contained in 8.2.4(C).

- Projects of 4-5 units will be eligible for the density bonuses in section 8.2.4(C), as long as they are of a use, and in a zone contained in those tables. This provision is intended to permit smaller apartments and townhouses, filling a need for residents who don’t necessarily want (or may not be able to afford) a single-family home. This provision can help reduce land costs by allowing a four-unit townhouse in place of a duplex, for example.

Historically, Arlington has had mixed results with affordable housing production, mainly due to the limited opportunity to build projects of six units or more. It is my hope that the density bonuses allow more of these projects to be built.

In conclusion, the problem of housing affordability in Arlington comes from a variety of pressures, is several years in the making, and will likely take years to address. I see Article 16 as the first step down a long road, and I ask for your support during the 2019 Town Meeting. I’d also ask for your support on articles 6, 7, and 8 which contain minor changes to make Article 16 work properly.