After a week of good coverage on the need for more housing units in the greater Boston region, on August 2, 2019 the GLOBE carried the following editorial, mentioning the situation in Arlington.

Good news? On housing? In Massachusetts?

Yes, that’s right. Even here in the land of the $600,000 starter home, a few forward-thinking cities and towns are starting to make progress on what sometimes seems like an intractable problem: the inadequate production of new housing that has sent the cost of renting or buying in Greater Boston into the stratosphere.

It’s way too soon to declare victory — not when the median sale price for a house in Massachusetts is $429,000 and $420,000 for a condo, according to the Warren Group. High prices happen when demand gallops past supply, causing buyers to bid up prices of existing homes to insane levels. In addition to squeezing renters and contributing to gentrification, the skyrocketing price of housing has evolved into a real threat to the region’s economic competitiveness.

“Greater Boston is losing current and potential domestic residents,” warned the Boston Foundation in its annual housing scorecard, “who are voting with their feet to live elsewhere for a variety of reasons.” Just on Tuesday, another report — this one from the real estate website Apartment List — found that only San Francisco has done a worse job than Greater Boston building new housing to respond to demand.

Thankfully, last year 15 cities and towns in Greater Boston made a joint pledge to pick up the pace of new housing construction by permitting 185,000 new housing units by 2030. Collectively, meeting that goal would mean tripling the pace of housing production. Some of the members of the group, called the Metropolitan Mayors Coalition, are doing their part to reach that goal faster than others — but almost all 15 report progress.

Even outside those three, there’s some impressive municipal-level progress. The Revere City Council approved development on the portion of the former Suffolk Downs racetrack that sits in that city, which will eventually bring in a whopping 2,700 housing units

Leading the way have been Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville, each of which has set numerical goals for housing production. Boston has been on a building spree and is on track to meet its goal of 69,000 new units by 2030. Cambridge volunteered 12,500 new housing units; and Somerville has said it will build 6,000. Committing to a specific goal is crucial: A hard number creates accountability for officials.

In Quincy, 1,500 housing units are under construction, and another 1,030 are either permitted or in the process of receiving permits. Medford has 497 housing units in construction. More than a thousand units are expected in Brookline over the next few years, in part thanks to the state’s 40B housing statute that lets developers bypass local zoning when towns have insufficient levels of affordable housing. Newton has 471 units under construction and another 273 permitted.

Other municipalities are working on plans or reforming zoning bylaws to set the stage for future growth. Austin Faison, Winthrop’s town manager, says that will involve setting a housing production goal. Everett rezoned land near the newly extended Silver Line, setting the stage for development. Braintree is in the process of updating its zoning bylaws that would include provisions for denser multi-family housing.

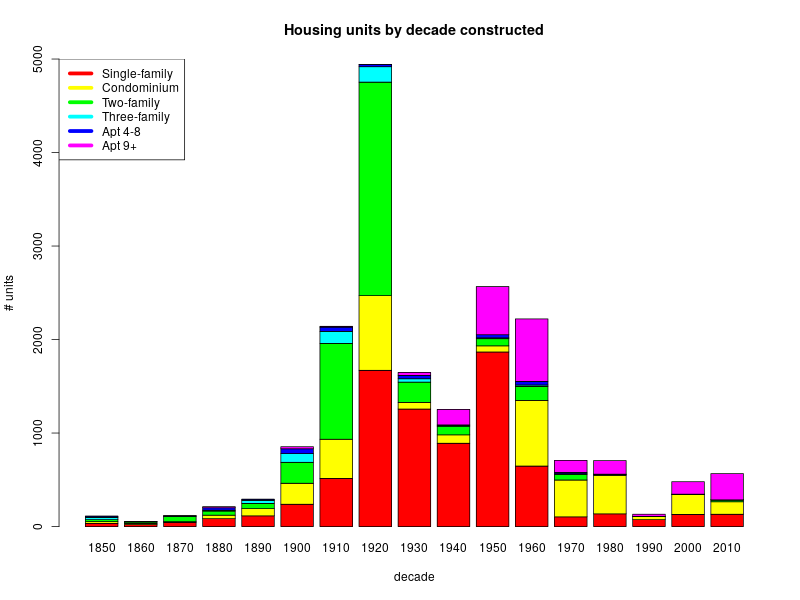

Arlington experienced a setback when its town meeting rejected an innovative plan to spur denser housing and allow so-called accessory dwelling units. Town manager Adam Chapdelaine said the town was now launching a “more cooperative effort” and would try again, and that the discussion would include coming up with a numerical goal.

The experience in Arlington points to one way the state can help municipalities. Town meetings and city councils require a two-thirds vote to change zoning, which can empower a small minority to thwart reforms needed to encourage housing. Governor Charlie Baker’s housing bill would change that by reducing to one-half the vote needed to change zoning — and deserves legislative approval pronto.

There’s one other way that the state can help, and this one won’t come as a surprise: better transportation. Access to transit can be a key to successful development. For instance, Revere wants a commuter rail stop at Wonderland. Without direct access to any rail service, Everett is banking on buses as part of its development plans.

Cities and towns that are moving forward on housing production inevitably encounter resistance, and they deserve great credit — not just for taking badly needed steps to build housing, but for doing so in a coordinated way. Keeping municipalities on the same page is part of what’s necessary to break down the longstanding barriers to housing in Massachusetts. As Chelsea city manager Thomas G. Ambrosino put it: “Having it be a region-wide effort and everyone rowing toward the same goal makes it easier for us to defend our efforts, because we can tell those who are critical about building that this is a regional need and everyone is in it together.”