Related articles

I’ve had an annual ritual for the past several years: obtain a spreadsheet of property assessments from the Town Assessor, load them in to a database, and run a series of R computations against the data. I started doing this for a number of reasons: to understand what was built where (our zoning laws have changed over time, and there are numerous non-conforming uses), the relationship between land and building values, the capital costs of different types of housing, and how these factors have changed over time.

I’d typically compile these analyses into a fact-book of sorts, and email it around to people that I thought might be interested. This year, I’m going to post the analyses here as a series of articles. This first installment contains basic information about Arlington’s low-density housing: single-, two-, and three-family homes, as well as condominiums. Condominiums are something of an oddball in this category — a condominium can be half of a two-family structure, part of a larger residential building, or somewhere in between. There’s a lot of variety.

Here’s a table showing how the number of units has changed over time, since 2013.

| land use | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Family | 7984 | 7983 | 7991 | 8000 | 7994 | 7994 | 7998 | 7999 |

| Condominium | 3242 | 3304 | 3367 | 3492 | 3552 | 3662 | 3726 | 3827 |

| Two-family | 2352 | 2332 | 2308 | 2282 | 2263 | 2218 | 2183 | 2139 |

| Three-family | 207 | 201 | 196 | 194 | 193 | 190 | 185 | 182 |

Arlington’s predominant form of housing — the single family home — has stayed relatively static; we’ve added 15 over the last seven years. The number of condominiums has increased significantly: +585 over seven years. That, coupled with the reduction of two-family homes (-213) and three-family homes (-25) leads me to believe that a fair number of rental units have been removed from the market.

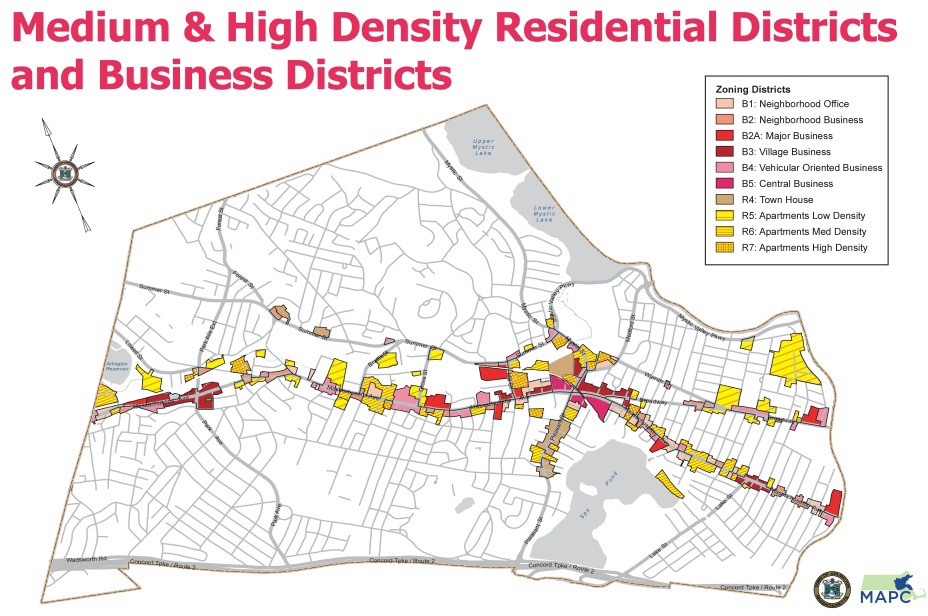

Next, I’d like to look at how these homes are spread across our various zoning districts. (The “Notes” section at the bottom of the post explains what the zoning district codes mean).

| Zone | Single-Family | Condo | Two-family | Three-family |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 8 | 22 | 13 | 11 |

| B2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| B2A | 1 | 18 | ||

| B3 | 59 | 4 | ||

| B4 | 1 | 59 | 5 | 5 |

| B5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| I | 8 | 18 | 7 | 1 |

| R0 | 502 | |||

| R1 | 6798 | 168 | 200 | 7 |

| R2 | 647 | 1816 | 1881 | 124 |

| R3 | 4 | 39 | 11 | 17 |

| R4 | 23 | 79 | 2 | 3 |

| R5 | 3 | 616 | 5 | 4 |

| R6 | 2 | 686 | 8 | 7 |

| R7 | 1 | 243 | 2 | 1 |

A few points to note:

- R0 is our newest district, which was established in 1991. It consists only of conforming single-family homes.

- R1 is Arlington’s original (per 1975 zoning) single-family district. It’s predominantly single-family homes, but there are a fair number of two-family homes, and even a few three-families. The presence of condominiums suggests additional multi-family homes (that consist of two or more condominiums)

- R2 is predominantly two-, and three-family homes. Although three-family homes are no longer allowed in this district, R2 has the largest number of three-families in town.

- Residential uses are no longer allowed in the industrial (I) districts, but the I districts contain 34 homes. These buildings pre-date the current zoning laws (aka “pre-existing non-conforming”). A good portion of the Dudley street industrial district is a residential neighborhood.

I’m pointing out these conformities (and non-conformities) for a reason. The zoning map (and use tables) dictate what is allowed today, along with specifying a vision for the future. Our zoning bylaw happens to contain a strong statement to this effect: “It is the purpose of this Bylaw to discourage the perpetuity of nonconforming uses and structures whenever possible” (section 8.1.1(A)). Despite the strong statement of intent, it can take decades (if not generations) for a built environment to catch up with the bylaw’s prescriptions.

I’ll finish this post with a breakdown of how condominiums are distributed across the various zoning districts:

| Zone | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | delta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N/A) | 14 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -14 |

| B1 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 6 |

| B2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| B2A | 19 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | -1 |

| B3 | 55 | 55 | 61 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 4 |

| B4 | 47 | 47 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 12 |

| I | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 0 |

| R1 | 140 | 144 | 146 | 148 | 150 | 154 | 162 | 168 | 28 |

| R2 | 1355 | 1406 | 1456 | 1518 | 1574 | 1670 | 1723 | 1816 | 461 |

| R3 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 31 | 31 | 37 | 37 | 39 | 17 |

| R4 | 65 | 67 | 67 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 14 |

| R5 | 616 | 616 | 616 | 616 | 616 | 616 | 616 | 616 | 0 |

| R6 | 630 | 632 | 635 | 683 | 683 | 683 | 686 | 686 | 56 |

| R7 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 0 |

The last column (“delta”) shows the difference between 2013 and 2020. The largest increase occurred in the R2 (two-family) district, followed by R6 (medium-density apartments, where most of the increase took place in 2014) and R1 (single-family).

That it will do it for the first installation. In the next post, we’ll look at how the cost (assessed values, actually) of Arlington’s low density housing has changed over the last seven years.

Here is a spreadsheet, containing the various tables shown in this article.

Notes

Arlington’s zoning map divides the town into a set of districts, and each district has regulations about what kinds of buildings and uses are allowed (or not allowed). The districts mentioned in this article are:

- B1 (Neighborhood Office district)

- B2 (Neighborhood Business distrct)

- B2A (Major Business District)

- B3 (Village Business District)

- B4 (Vehicular-Oriented Business District)

- I (Industrial District)

- R0 (Single-Family, large-lot district)

- R1 (Single-Family Distict)

- R2 (Two-Family District)

- R3 (Three-Family District)

- R4 (Townhouse District)

- R5 (Low-Density Apartment District)

- R6 (Medium-Density Apartment District)

- R7 (High-Density Apartment District)

Arlington’s Zoning Bylaw describes each district in detail (see sections 5.4.2, 5.5.2, and 5.6.2)

Prof. Christophe Reinhardt runs the MIT Sustainable Design Lab. On Nov. 25, 2019 he gave a very interesting presentation, including talk and slides, that shows a pathway to make more housing, all kinds of housing, and greater housing density both more palatable in Arlington, and actually desirable. He also stressed the importance of paying attention to housing now in order to meet the climate change challenge. Charts (starting about 10 min in) show how drastically we need to reduce our carbon footprint to reach net zero by 2050. Buildings today account for about 40% of our carbon emissions world wide. What we build today will likely be around through 2050.

Paying attention to housing design is important to create a sustainable environment.

Here is the link for the Reinhardts talk and slide show:

http://scienceforthepublic.org/energy-and-resources/designing-sustainable-urban-development

or see it on youtube: https://youtu.be/YAeCvUZmUrI

He uses research, drawn from around the world and locally, to show what measurable attributes make local communities desirable to live in and what attributes of housing make residents happy.

Key attributes for success (slide is at about 18:15 min. in presentation):

1. Economic opportunities (proximity to work opportunities)

2. High quality living (daylight access for buildings, streets, walkable, mixed use, micro-units, vibrant public spaces, organic food, fitness opportunities)

3. Sustainability (comfortable work and play and living spaces, resource efficiency)

The presentation was arranged by the Robbins Library. It was developed and recorded by Science for the Public as part of it’s lecture series.

For more information on sustainability and cities, cities and local municipalities are beginning to recognize the important linkages between urban resiliency, human well-being, and climate change mitigation and adaptation activities. https://news.mongabay.com/2019/11/how-cities-can-lead-the-fight-against-climate-change-using-urban-forestry-and-trees-commentary/ Courtesy of Science for the Public Interest Weekly News Roundup.

(For more opportunities to learn about sustainability, buildings and cities, sign up for the FREE MITx “Sustainable Building Design” online course which starts January.)

A large part of the debate about the proposed Zoning issues in Arlington revolves around a perspective of Arlington’s culture and how best to maintain it. Can we freeze in time the small, less expensive homes in our R1 & R2 districts? Can we continue to provide low cost rental housing to people in the R4 to R7 districts, housing that is now quite old and is below market rent because it has not been adequately maintained? Or can we reach a consensus about what we most value in Arlington’s culture and set a path to ensuring its preservation for the future?

In 2015 Arlington Town Meeting voted to approve the Master Plan which contained the following set of housing related values and goals for the future of Arlington:

- Encourage mixed-use development that includes affordable housing, primarily in well-established commercial areas.

- Provide a variety of housing options for a range of incomes, ages, family sizes, and needs.

- Preserve the “streetcar suburb” character of Arlington’s residential neighborhoods.

- Encourage sustainable construction and renovation of new and existing structures

The Zoning Articles proposed for the 2019 town meeting represent four years of study, reflection and community dialogue. They are precisely intended to further the values and goals that the 2015 Town Meeting voted for.

Our Culture

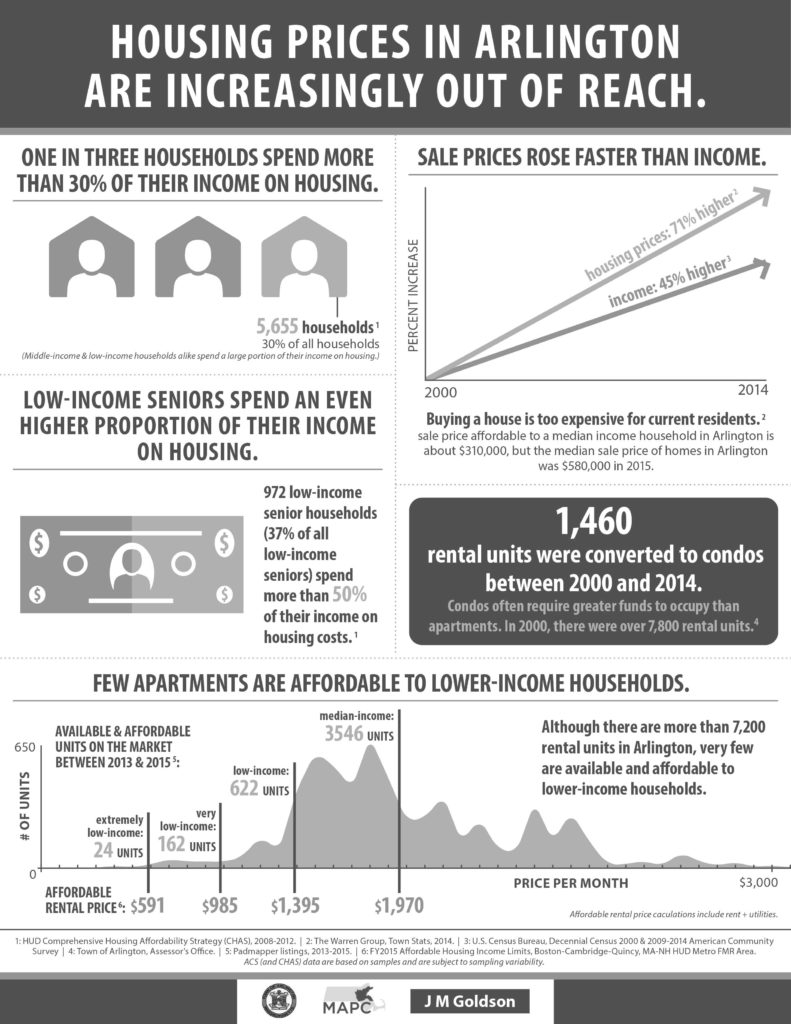

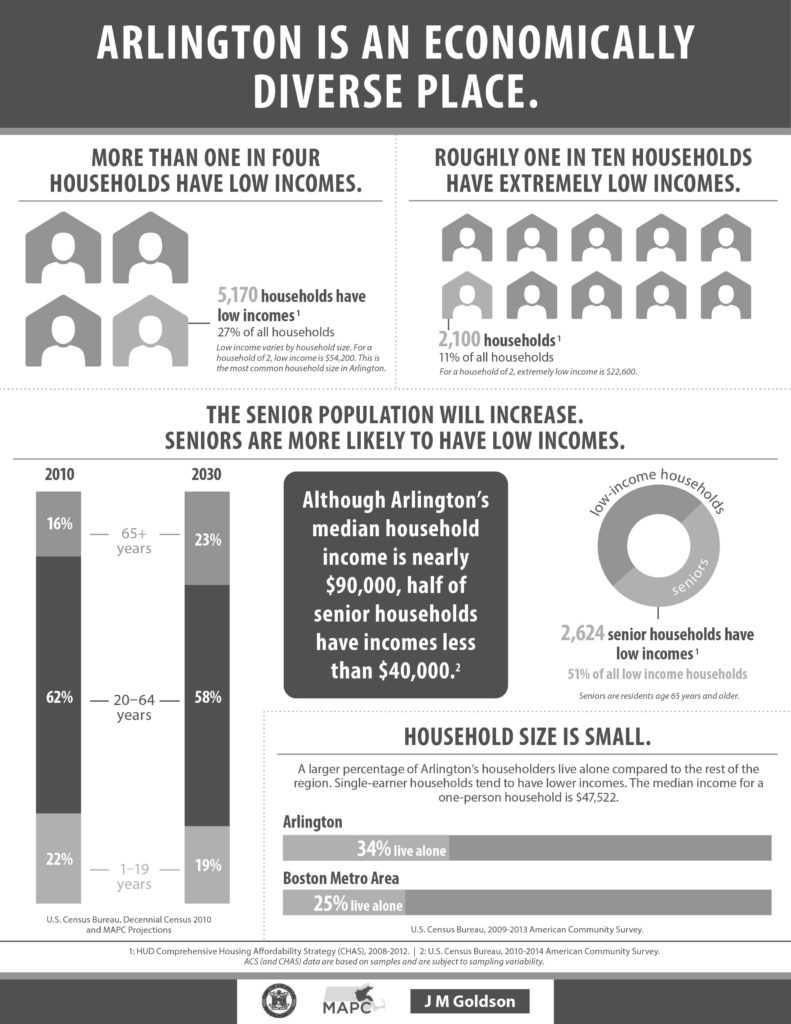

Arlington has long been a community that cherishes its diversity of housing types and its diversity of income ranges. In recent years, with the regional pressure on land values as more people want to live in good school districts, with good transportation, near their jobs, the pressure on Arlington property values has been extreme. According to the Town’s Master Plan, Arlington does have a more diverse housing stock than most neighboring communities. The type, density and population varies by neighborhood (see Master Plan Ch. 5, Housing Excerpt). Most cities and towns around Arlington experienced a significant rise in housing values from 2000 to 2010. A 40 percent increase in the median value was fairly common. However, Arlington experienced more dramatic growth in housing values than any community in the immediate area, except Somerville. In fact, Arlington’s home values almost doubled.

Tools to Maintain Diversity of Housing

Articles 15 & 16 are two very important “tools” to meet the goals of preserving our diversity of housing.

Over 60% of Arlington’s housing units were built before 1950. Many of those units that we think of now as “affordable” will be needing major renovation or tear down and rebuild in the next few years. Private developers can come in now, buy the buildings and rebuild for market rate (think Boston prices) units. Article 16 gives the town control over these rebuilds, encouraging more housing and more “permanent” affordability.

Article 15, allows Accessory Dwelling Units (“granny units”) after a public hearing and under specific conditions. This will open the town to many lower priced living spaces for students, seniors, etc. throughout the Town.

Arlington values its culture of diversity in housing styles and incomes. Given the pressure regionally for people to find housing in good communities, and bring larger incomes to pay for that housing, Arlington risks losing its culture if the Town does not act NOW to protect it by approving these zoning articles.

Welcome to the redesigned Equitable Arlington website! We know that Arlington values openness and diversity, a greener future, and vibrant neighborhoods and downtowns—but our current zoning is holding us back. We’re advocating for change because we recognize that the choices we make on zoning and housing policy are key to living those values. We are committed to strengthening our community through respectful dialogue and by listening to our neighbors. Our aim with this site redesign is to share accurate and relevant information to help inform such conversations.

With this redesigned site we have:

- Answered some of the most common questions that have come up in our conversations with other residents.

- Created a zoning dictionary with explanations of many of the terms that pepper zoning discussions.

- Gathered a list of resources, where you’ll find everything from short explainer videos to detailed research

- Developed a history of zoning timeline that shows how Arlington’s history fits into the larger context of government actions.

If you’re not familiar with us, I hope you’ll take a minute to read our mission and why our work matters. I also hope you’ll scroll through to meet us, see some of our smiling faces, and read in our own words why we do this work. We’re renters and homeowners, long time residents and newcomers to town who come to this work with a variety of viewpoints and lived experiences!

We believe Arlington can be a leader in the greater Boston area by the choices we make to create more equitable housing policy. Our local actions have effects that go beyond our borders. Arlington has recognized our power to make an impact and has been a regional leader on many issues.

We can channel this same energy and our values to make sure Arlington has the vibrant sustainable and equitable future we all want. To succeed, we need engaged residents who understand the issues, who can balance competing interests, and who are willing to do the necessary hard work. Please join us in building a more equitable Arlington!

Massachusetts is experiencing a housing affordability crisis and a climate crisis. For these reasons, Mothers Out Front Arlington supports changes in zoning by-laws that allow greater density in housing near public transit. Mothers Out Front is supportive of the passage of a meaningful MBTA Communities Act that encourages the development of more multi-family housing and a greater diversity of home types in Arlington. A revised zoning by-law to allow for more multi-family housing will reduce pressure to build single family homes on undeveloped land elsewhere in Massachusetts. This safeguards undisturbed ecosystems and provides real alternatives to automotive commutes in the region, reducing both congestion and fossil fuel emissions. In addition, passing this by-law will allow Arlington to participate in the Massachusetts pilot for communities to build fossil fuel-free homes, thus ensuring that new construction in Arlington supports our net-zero climate goals.

Mothers Out Front Arlington respects the public engagement activities that inform the Working Group’s MBTA Communities Act proposal. We appreciate that the Working Group is working with the Town to identify opportunities for developer incentives to encourage public open spaces, mitigate heat islands, and increase the tree canopy. Similarly, the Town’s commitment to maintaining current (and incentivizing higher) zoning requirements for affordable housing also is important to our group. For these reasons, Mothers Out Front Arlington strongly urges the Arlington Redevelopment Board to accept the MBTA Communities Act plan as proposed by the Working Group.

The discussions on zoning have been confusing because while zoning covers ALL of Arlington’s land and the zoning bylaws for all Arlington’s zones are referenced, the key issues of greatest interest to Town Meeting are the discussions about increasing density. These discussions pertain ONLY to those properties currently zoned as R4-R7 and the B (Business) districts. These density related changes would affect only about 7% of Arlington’s land area. The map shows the specific zones that would potentially be affected. They lay along major transportation corridors.

The City of Somerville estimates that a 2% real estate transfer fee — with 1% paid by sellers and 1% paid by buyers, and that exempts owner-occupants (defined as persons residing in the property for at least two years) — could generate up to $6 million per year for affordable housing. The hotter the market, and the greater the number of property transactions, the more such a fee would generate.

Other municipalities are also looking at this legislation but need “home rule” permission, one municipality at a time, from the state to enact it locally. Or, alternatively, legislation could be passed at the state level to allow all municipalities to opt into such a program and design their own terms. This would be much like the well regarded Community Preservation Act (CPA) program that provides funds for local governments to do historic preservation, conservation, etc.

This memorandum from the City of Somerville to the legislature provides a great deal of information on the history, background and justification for such legislation.

House bill 1769, filed January, 2019, is an “Act supporting affordable housing with a local option for a fee to be applied to certain real estate transactions“.

COMMENT:

KK: This article suggests Arlington may be likely to pass a real estate transfer tax: https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/12/19/boston-one-step-closer-to-a-luxury-real-estate-transfer-tax/

This letter appeared in the Boston Globe on Dec. 19th. It’s reprinted

here with permission from the author, Eugene Benson.

The Dec. 12 letter from Jo Anne Preston unfortunately repeats misinformation making the rounds in Arlington (“Arlington is a case study in grappling with rezoning“).

At April Town Meeting, the Arlington Redevelopment Board recommended a vote of no action on its warrant article that would have allowed increased density along the town’s commercial corridors in exchange for building more affordable housing (known as “incentive zoning”), when it became obvious that the article would be unlikely to gain a two-thirds vote for passage, in part because of the complexity of what was proposed.

A warrant article to allow accessory dwelling units in existing housing (“in-law apartments”) gained more than 60 percent of the vote at Town Meeting but not the two-thirds vote necessary to change zoning.

The letter writer mentioned “naturally occurring affordable apartment buildings.” The typical monthly rent for an apartment in those older buildings ranges from about $1,700 for a one-bedroom to about $2,300 for a two-bedroom, according to real estate data from CoStar. Those are not affordable rents for lower-income people. For example, a senior couple with the national average Social Security income of about $2,500 per month would spend most of their income just to pay the rent.

We need to protect the ability of people with lower incomes to withstand rent increases and gentrification. That, however, requires a different approach than hoping for naturally occurring affordable housing to be there even five years from now.

Eugene B. Benson

Arlington

The writer’s views expressed here are his own, and are not offered on behalf of the Arlington Redevelopment Board, of which he is a member.