Jennifer Susse authored this letter on January 20, 2020. Ms. Susse is a member of the Arlington School Committee and a Town Meeting Member. She closely follows the costs and demographic trends of school enrollment and of Town finances.

I write in support of efforts to increase housing in Arlington, both as a resident and as a member of the School Committee. I support these efforts not in spite of their potential effects on our schools, but because of their potential effects on both schools and town.

I have often spoken to the community about our rapid enrollment growth — over 2,000 students added in the last 25 years, 60 percent of those in the last 10 years. Because of these large enrollment increases the Arlington Public Schools have had to add capacity, which the town has generously supported. So how can I be in favor of adding more housing to Arlington, and thus potentially adding even more students to our already stressed school facilities?

Losing diversity

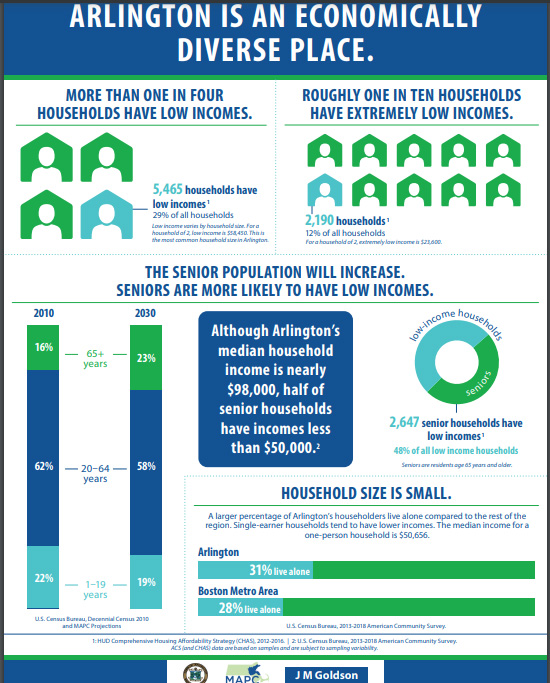

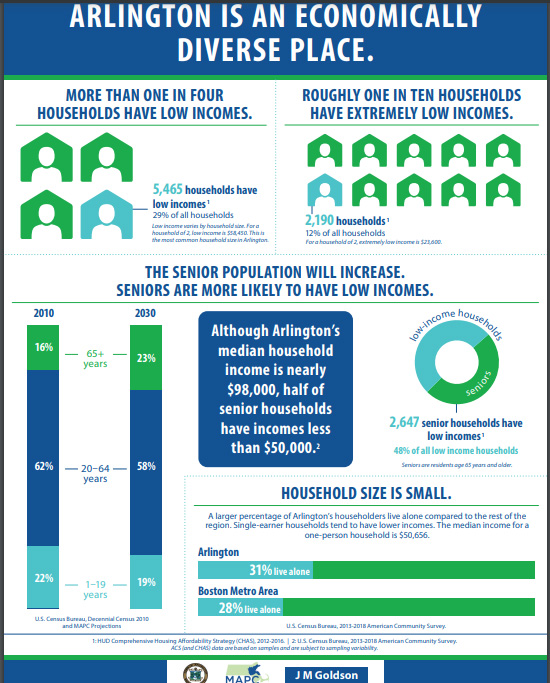

I will get to the capacity issue in a bit, but first I want to point out that in the last 30 years Arlington has lost both economic and generational diversity. The story about the loss of economic diversity is well known; the loss of generational diversity less so.

Between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of residents between 20 and 34 dropped from 28 percent to 17 percent. During that same period, the population over 65 dropped from 18 percent to 16 percent. What replaced these demographic groups were primarily residents between the ages of 35 and 54 and 0 and 14. In other words, mostly families with school-aged children. The loss of both types of diversity weakens the fabric of our community. However, the loss of generational diversity also weakens the town’s finances.

The average cost to the town of an additional student is about $8,500, a number that includes what’s known as the Enrollment Growth Factor (the amount that the town gives to the schools for each additional student in the system, currently at 50 percent of the per pupil cost of the preceding year, or $7,297), as well as the average cost of the benefits that the town pays for new hires.

What this means is that during the time a household has children in the school system, it is likely receiving more in benefits than it pays in taxes. For the town’s finances to work, we also need people who do not have children to live and pay taxes in Arlington, including young adults and older adults for whom Arlington is becoming less affordable because of condo conversions, teardowns, etc.

Overcrowded classrooms

But what about our overcrowded classrooms? The answer is that given the type of housing likely to be created on the main corridors, and the timing of that housing construction, I am not worried about further stresses to our school facilities.

By the time new housing is built, our elementary-aged population will likely be in modest decline. Five to 10 years out we expect to see enrollment stabilize at the middle and high school levels as well. That does not mean that we will have tons of extra space; just that we will no longer be in danger of taking over art, music, and literacy rooms for general classroom use.

Enrollment projections made by Dr. Jerome McKibbin in 2015 have so far been fairly accurate. His revised projections show that, without additional housing, we are expected to have 350 fewer elementary-aged students in the Arlington Public Schools 12 years from now than we have today.

The discussion about housing in Arlington reminds me of the discussion a few years ago over the Affordable Care Act. At that time, there was a lot of anxiety about potential changes to the health-care system, but insufficient appreciation (in my opinion) of the then current trends.

Zoning changes

Any discussion of zoning changes in Arlington must take an honest look at where we are now, and the direction we are headed in if there were no zoning changes. Our current trends have us losing natural affordability and economic and demographic diversity because of teardowns, condo conversions and sharp price increases. We don’t have the option to freeze Arlington as we know it today (or 10 years ago) in place.

In closing, I would like to say that I am proud of our excellent schools and strongly believe that families who have recently moved to Arlington have strengthened our community, but I do not want Arlington to become a place where people move in with toddlers and move out soon as their children graduate from high school. The current trends have us losing both economic and generational diversity, which threatens not only our community and civic life, but our financial health as well. Adding more and diverse housing can help.

by Andy Greenspon

Image credit: Henry Hudson Kitson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 2023, Lexington was one of the first towns to comply with the State “MBTA Communities” law (MBTA-C) by adding 227 acres to several multifamily overlay zones. When discussing this proposal, it was estimated to possibly generate 400-800 units in 4-10 years. However, after receiving building permit applications for about 1,100 units in the first year (including 160 inclusionary affordable units), Lexington passed Article 2 at a Special Town Meeting recently, which decreased the amount of land in these zones to approximately 90 acres. What can Arlington learn from Lexington’s experience?

Overall, Lexington’s experience shows us that developers are willing and able to build multifamily housing on large lots that aren’t very built up, and that MBTA-C can be successful in adding new housing in some circumstances. However, Arlington has few if any large, sparsely-built parcels zoned to allow multifamily housing under MBTA-C. As such, Arlington is unlikely to add significant amounts of new housing or affordable housing as a result of the MBTA-C overlay passed at Town Meeting in fall of 2023.

Many of the parcels in Lexington’s MBTA-C zone are multiple acres each, are underutilized, and contain older office space. In contrast, Arlington’s MBTA-C parcels are much smaller and mostly covered with existing buildings, typically residential.

The largest development approved under MBTA-C so far in Lexington is at 3-5 Militia Drive. This land is three very large parcels containing a couple older office buildings, a previous religious institution, and giant surface parking lots. Therefore, such a property was already primed for redevelopment and the large lots allowed for 292 units to be approved. These parcels are also within walking distance of Lexington Town Center and the Minuteman Bike path, so multi-family housing on this location is a great use.

In contrast, there are no similar parcels in Arlington in the MBTA-C zone with large surface parking lots and aged office space that could be redeveloped in such a manner. One of the few parcels in Arlington that is somewhat similar to the planned parcels for redevelopment in Lexington would be the Walgreens at 324 Massachusetts Ave, 1.5 acres with a surface parking lot. However, this parcel was specifically excluded from the MBTA-C overlay along with all other business parcels to avoid displacing any existing business space. And the parcel is unlikely to be redeveloped one way or another unless Walgreens chooses to close their business and sell the parcel to a developer.

In short, compared to Lexington, Arlington is “built out” insofar as almost every parcel is utilized in some manner with high lot coverage. The original Lexington MBTA-C zone contained many parcels with low lot coverage, large surface parking lots, and underutilized office space, all attributes that make such parcels more likely to be sold to a developer to construct housing if permitted by zoning.

Last, while 1,100 units have been permitted so far, this does not mean all these units will be constructed given current financial uncertainty in the economy and high interest rates. It will also take several years for these properties to be completed and prepared for occupancy. As such, the original estimate of 400-800 units in 4-10 years (an estimate that actually widely ranges from 40 units all the way to 200 units per year) may in fact not be that far off from the final numbers once buildings are completed. The parcels most primed for redevelopment were acquired and permitted first. Finally, it is not entirely clear how many more parcels would have been redeveloped in the next 5-10 years had the Lexington MBTA-C zoning not been reduced in size.

Most privately owned lots in Arlington are less than ⅓ of an acre with many much smaller, significantly limiting the amount of new housing development on any single parcel. Almost all of these lots are covered by existing buildings, and some of those buildings are condominiums. Therefore, in order for a large new construction project to occur on such parcels in Arlington’s MBTA-C multifamily zone, all of the following would have to take place:

Meanwhile, properties in Arlington generally turn over at a fairly slow and steady pace. This is in contrast to underused large commercial properties, whose owners are more eager to sell.

With simulation modeling performed on potential rate of redevelopment, the Arlington Redevelopment Board’s 2023 Report to Town Meeting on the MBTA-C proposal projected that 15–45 parcels could be redeveloped over the next ten years, for a net increase of 50–200 new units or 5–20 per year, far fewer than even the initial Lexington housing unit construction estimates at the time of passage of their initial MBTA-C zoning.

In fact, Arlington has seen even less than the low end estimate of 5 units per year so far since our MBTA-C zoning became effective. Only a single project has been permitted so far, which would turn an existing 2-unit building into 4 units, a potential net gain of 2 housing units.

Report by Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O’Regan, Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability, NYU Furman Center 8/20/18

Some affordable housing advocates question the premise that increasing the supply of market-rate housing will result in more affordable housing. This paper addresses the key arguments these “supply skeptics” make. Considering both theory and empirical evidence, the authors conclude that adding new market-rate homes moderates price increases does make housing more affordable to low- and moderate-income families.

At the outset, the authors review the relevant studies and conclude that “the preponderance of the evidence shows that restricting supply increases housing prices and that adding supply would help to make housing more affordable.” They then turn to several arguments the supply skeptics make. One key issue is whether adding housing in a part of the housing market will affect prices in another. The housing market is not uniform but composed of various submarkets. These submarkets relate to each other in complex ways. Critically, however, if demand forces up prices in a higher-end submarket, some buyers will turn to the next segment down and bid up prices there, generating a cascade. Adding supply at higher levels reduces this cascade and relieves price pressure all the way down. Empirical research indicates that this “filtering” process happens surprisingly quickly.

Supply skeptics may also fear that construction of new housing will exacerbate affordability problems by raising neighborhood rents or prices, fueling gentrification, and potentially displacing existing residents. New construction can have both positive and negative effects on prices or rents of nearby homes. New housing may an amenity that makes a neighborhood more attractive – and expensive. But it also absorbs demand and may reduce the incentive to upgrade existing housing to please high-end buyers. The evidence on the net effect of these effects is unclear. An important California study indicates that the production of market rate housing was associated with a lower probability that low-income residents in the neighborhood would experience displacement. But more research is needed.

The authors point to additional disadvantages of limiting supply, including pushing lower-wage workers to live in distant suburbs, where long commutes add to regional traffic woes and greenhouse gas emissions. They stress, however, that increased supply, while essential, is not sufficient to address the affordability challenge. Government intervention through subsidies and other measures is critical to ensure that housing supply is added at prices affordable to a range of incomes, and especially the lowest ones.

(presented by Adam Chapdelaine, Town Manager, to Select Board on July 22, 2019)

Since 1980 the price of housing in Massachusetts has surged well ahead of other fast growing states including California and New York. While the national “House Price Index” is just below 400, four times what an average house might have cost in 1980, a typical house in Massachusetts is now about 720% what it was in 1980. Median household income in the state has only increased about 15% during the same period. No wonder people in Arlington are feeling the stresses of housing costs if they want to live here and are feeling protective of the equity value time has provided them if they bought years ago.

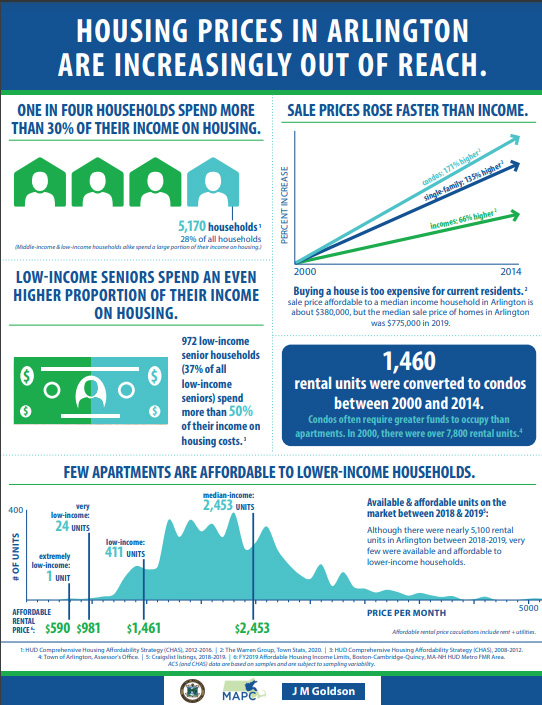

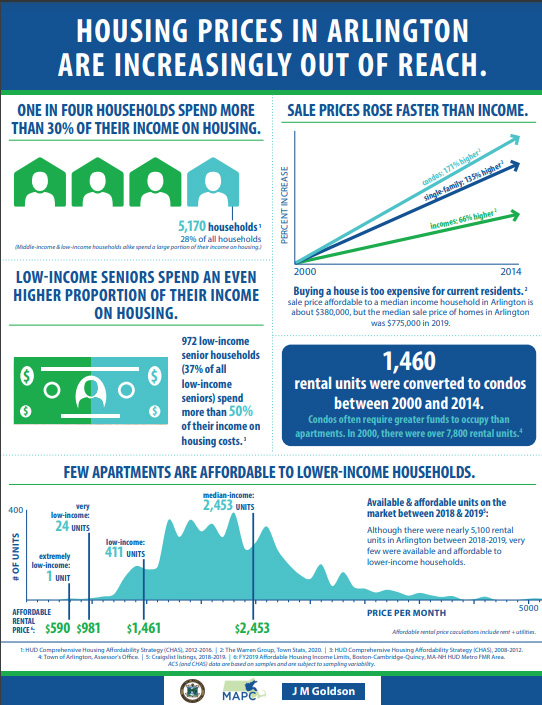

In response to concerns about zoning, affordable housing and housing density, the Town joined the “Mayors’ (and Managers’) Coalition on Housing” to address these growing pressures. This 12 page slide deck presentation outlines the key data points, the number of low and very low income households in Arlington, the rate of condo conversion that is absorbing rental units, etc.

Solutions are offered including:

• Amendments to Inclusionary Zoning Bylaw

• Housing Creation Along Commercial Corridor – Mixed Use & Zoning Along Corridor

• Accessory Dwelling Units – Potential Age & Family Restrictions

• Other Tools Can Be Considered That Are Outside of Zoning But Have An Impact on Housing

Chapdelaine’s suggested next steps are:

• Continued Public Engagement

• Town Manager & Director of DPCD Meet with ARB

• Select Board & ARB Hold Joint Meeting in Early Fall

• ARB Recommends Strategies to Pursue in Late Fall/Early Winter

The Select Board approved the suggested next steps and a joint ARB/ Select Board meeting should be scheduled in the near future.

Note from Reporter: As a community, Arlington has long prided itself on its economic diversity. With condo conversions, tear downs leading to “McMansions”, higher paid workers arriving in response to new jobs, etc., Arlington is at great risk of losing this diversity that has long enriched the community. Retirees looking to downsize and young people who have grown up in Arlington looking for their first apartment are finding it impossible to stay in town. Shop keepers and town employees are challenged to afford the rising housing costs. With a reconsideration of zoning along Arlington’s transit corridors, Arlington NOW has an opportunity to create new village centers, like those recommended in the recent STATE OF HOUSING report. These village centers along our transit corridors could be higher, denser but also offer the compelling visual design and amenities desired by people who want to walk to cafes, shops and public transit.

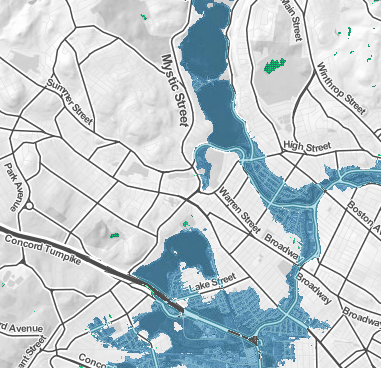

Climate Central’s Surging Seas global Risk Zone Map provides the ability to explore inundation risk up to 30 meters across the world’s coastlines as well as local sea level rise projections at over 1,000 tide gauges on 6 continents.

Set the map for Boston MA and focus in on the Arlington area to see how the town would be affected by rising sea levels, as predicted over the next few decades.

Map areas below the selected water level are displayed as satellite imagery shaded in blue indicating vulnerability to flooding from combined sea level rise, storm surge, and tides, or to permanent submergence by long-term sea level rise. Map areas above the selected water level are shown in map style using white and pale grays. The map is searchable by city, state, postal code, and other location names. The map is embeddable, and users can customize and download map screenshots using the camera icon in the top right of the screen.

For map areas in the U.S., the Risk Zone map incorporates the latest, high-resolution, high-accuracy lidar elevation data supplied by NOAA, displays points of interest, and contains layers displaying social vulnerability and population density. For map areas outside the U.S. the map utilizes elevation data from NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM).

According to Richard Rothstein in his 2017 book, Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, “we have created a caste system in this country, with African-Americans kept exploited and geographically separate by racially explicit government policies,” he writes. “Although most of these policies are now off the books, they have never been remedied and their effects endure.” Zoning was one of the policies that contributed significantly to this outcome.

Here are some highlights, selected for Arlington readers, from this book:

P. VII

“… until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state and local governments defined where white and African Americans should live. Today’s racial segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law and regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that is effects endure to the present time. Without our government’s purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causes – private prejudice, white flight, real estate starring, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregation – still would have existed but with far less opportunity for expression. Segregation by intentional government action is not de facto. Rather, it is what courts call de jure: segregation by law and public policy. “

1917 – Buchanan v. Warley – Supreme Court case that overturned racial zoning ordinance in Louisville, Kentucky. Municipalities ignore and fought against this. Kansas City and Norfolk through 1987.

1948 – Shelley v. Kraemer – Although racially restrictive real estate covenants are not per se illegal, since they do not involve state action, a court cannot enforce them under the Fourteenth Amendment. FHA continues to not insure mortgages for African Americans.

1968 – Fair Housing Act endorsed the rights of African Americans to to reside wherever they chose and could afford. Finally ending the Federal Housing Administration’s’ role in mortgage insurance discrimination.

1969 – Mass 40B law passed

1972 – Head of Arlington ARB editorial talking about preserving the suburban way of life

1973 – Town Meeting passes moratorium on apartment construction

1975 – Arlington zoning re-do that all but stops development

1977 – Supreme Court upholds Arlington Heights, IL zoning that prohibited multi-unit development anywhere by adjacent to an outlying commercial area. In meetings leading to the adoption of these rules, the public urged support for racially discriminatory reasons.

p. 179″Residential segregation is hard to undo for several reasons:

A study by Elise Rapoza and Michael Goodman shows that new housing construction in MA does not have an adverse affect on municipal or school budgets. And when it might, state funding covers the difference. This study contradicts the often heard argument against new housing development, especially multi-family housing, because it, the argument claims, it will have a negative fiscal impact on communities.

In the aggregate, development of new housing offers net fiscal benefit to both municipalities and the state. Additional analysis validates a second study which found that increased housing production does not predict enrollment changes in Massachusetts school districts. In the new study, a distinct minority of municipalities did incur net fiscal burdens—burdens that the net new state tax proceeds associated with the development of new housing are more than sufficient to offset.

by Laura Wiener

If you’ve lived in Arlington for a while, your housing costs, whether you rent or own, might be well below what they are for newcomers. Perhaps you, or someone you know is experiencing scary annual rent increases, or would like to buy a house but can’t get near Arlington’s $1 million-plus median price tag.

Arlington, and much of the Commonwealth, has a shortage of housing that is driving up housing prices and increasing homelessness. Renters are particularly hard hit, with median rents over $2500/month. About 1/3 of Arlington’s renters pay more than 30% of their income for housing. In order to get that rent down to something affordable for a low-income household, subsidies are needed. Arlington has been very supportive of building affordable housing, using its CDBG (Federal Community Development Block Grant) and CPA (local Community Preservation Act) funds to that end. It has also worked cooperatively with the Arlington Housing Authority and Housing Corporation of Arlington in support of their affordable housing projects. These subsidy dollars are necessary but not sufficient for building affordable housing.

Land cost is one thing that makes building any housing expensive, and one way to decrease the cost of building affordable housing is to allow more units to be built on a given piece of land. But our zoning limits much of our town to single- and two-family homes on a lot. The Affordable Housing Overlay allows more units to be built on a lot, throughout the Town, and targets those who need it most—low-income households.

A zoning overlay is an alternative set of zoning requirements that can be applied on a piece of land. A builder can choose to build under the alternative Overlay Zoning rules, or under the original zoning, known as the Underlying Zoning. In this case, the proposed Affordable Housing Overlay Zoning can be applied anywhere, on any lot, if at least 70% of the units are priced to be affordable to a household at or below 60% of median income. If 70% of units are affordable, then the structure can be up to 2 stories taller than with the underlying zoning. In addition, any number of units can be built, so long as yard and setback requirements are met. One additional change is that the parking requirement would be a minimum of ½ space per unit. This reflects the actual parking usage at existing affordable housing owned by the Housing Corporation of Arlington. This proposal includes both rental and ownership units that are affordable.

A group of Arlington residents is proposing an amendment to our current zoning to include an Affordable Housing Overlay. This proposal will come before the Redevelopment Board for hearings in winter 2025 (probably during February or March), and then go to Town Meeting in spring 2025. There has already been one informational meeting on November 7 (slides and video), and there may be additional public informational meetings scheduled.