Like numerous metro areas in the United States, Greater Boston has both a shortage of housing and high housing costs. According to a recent presentation by Town Manager Adam Chapdelaine, Boston and the immediate surrounding communities added new 148,000 jobs and 110,000 new residents in the period 2010–2017. But despite the increase in jobs and population, we’ve only permitted 32,500 new homes.

This shortage led the Metro Mayors Coalition — a group of 15 mayors and town managers in the Greater Boston area — to establish a housing task force. The task force set a goal of producing 185,000 new homes during the period 2015–2030. There’s a lot said about that number, and the commitments each community has been willing to make. 185,000 new homes is the big ask, but there’s more to the MMC’s efforts than a simple production goal.

The MMC established a set of ten guiding principles, which are as follows:

In addition to the guiding principals, the Task Force’s web site lists dozens of strategies for consideration. Some focus on the three cost drivers of housing production: land, labor, and materials. Others focus on more holistic aspects, like fairness and diversity. The overall list of strategies includes: tenant protections like rent control, requirements for just-cause evictions, and the right of first refusal; community benefit agreements, housing cooperatives, and community land trusts; transfer fees, linkage fees, vacancy taxes, and anti-speculation taxes; use of prefabricated homes and modular construction techniques; and a variety of approaches for community engagement and education.

In summary, the MMC has put a lot of thought into the process — far more than simply coming up with a number.

A few days ago, the Boston Globe ran an article titled “2021 set records in Boston Housing Market. What now?“. It’s not unusual to see stories about housing in the news — the market is highly competitive and the sale prices can be jaw dropping. Jaw dropping can take several forms: from the new (and used) homes that sell for over two million dollars, to the amount of money that someone will pay to purchase a small post-war cape (around $900,000, give or take).

According to the globe article, the Greater Boston Association of Realtors estimates that the median price of a single family homes in the Boston area rose 10.5% in 2021, to $750,000. Arlington is comfortably in the upper half of this median: according to our draft housing production plan the median sale price of our single family homes was $862,500 in 2020, and rose to $960,000 in the first half of 2021 (see page 39).

In June 2021, I got myself into a habit of sampling real estate sales listed in the Arlington Advocate, and compiling them into a spreadsheet. My observations are generally consistent with the sources cited above; Arlington’s housing is expensive and it’s appreciated rapidly, particularly in the last 6–10 years. It’s a great time for existing owners, but less so if you’re in the market for your first home.

We’re actually facing two problems, which are related but not identical. The first is high cost, which creates financial stress and a barrier to entry (though it is a boon for those who sell). The second problem is quantity; there are regional and national housing shortages, and that contributes to high prices and bidding wars.

Addressing these challenges will require collective effort on behalf of all communities in the metro area; this is a regional problem and we’ll all have to pitch in. There isn’t a single recipe for what “pitching in” means, but here are some for what communities can do.

First, produce more affordable housing. Affordable housing is a complex regulatory subject, but it basically boils down to two things: (1) the housing is reserved for households with lower incomes than the area as a whole, and (2) there’s a deed restriction (or similar) that prevents it from being sold or rented at market rates. Affordable housing usually costs more to produce than it generates in income, and the difference has to be made up with subsidies. It takes money.

Second, simply produce more housing. This is the obvious way to address an absolute shortage in the number of dwellings available. Some communities have set goals for housing production. Under the Walsh administration, Boston set a goal of producing 69,000 new housing units by 2030. Somerville’s goal is 6000 new housing units, and Cambridge’s is 12,500 (page 152 of pdf). To the best of my knowledge, Arlington has not set a numeric housing production goal, but it’s something I’d like to see us do.

Finally, communities could be more flexible with the types of housing they allow. Arlington is predominantly zoned for single- and two-family homes. The median sale price of our single family homes was $960,000 during the first half of 2021, and a large portion of that comes from the cost of land. That’s the reality we have, and the existing housing costs what it costs. So, we might consider allowing more types of “missing middle” housing, where the per dwelling costs tend to be lower: apartments, town houses, triple-deckers, and the like.

Of course, this assumes that our high cost of housing is a problem that needs to be solved; we could always decide that it isn’t. In the United States, home ownership is seen as a way to build equity and wealth. It’s certainly been fulfilling that objective, especially in recent years.

The Massachusetts Housing Partnership put together this 2018 guidebook, v.3, to help municipalities adopt Municipal Affordable Housing Trust Fund (MAHT) legislation to suit the specific needs of each municipality.

Arlington is considering the acceptance of enabling legislation in the November 2020 Virtual Town Meeting to create the Town’s own MAHT. This will enable the Town to create a vehicle for receiving and spending funds to assist low and moderate income individuals and families to move toward greater housing stability. The MAHT does not provide money, but it does provide a place where the Town can receive money from a variety of sources to be used for furthering affordable housing. Examples include payments from developers, contributions from bequests and, if approved, a real estate transfer tax on the sale of higher priced homes in Arlington.

Municipal Affordable Housing Trust: how to envision, gain support, and utilize a local Trust to achieve your housing goals.

For more information on how this MAHT can benefit Arlington see: https://equitable-arlington.org/2020/11/09/arlington-affordable-housing-trust-fund/

Issues of supply, affordability, and equity all contribute to an ongoing housing crisis in Massachusetts. Among U.S. metro areas with knowledge-based industries, metro Boston ranks near the bottom in housing production and near the top on development costs. Due to the latter, production of new affordable housing units has scarcely increased over the past decade. And largely decentralized authority over land use regulations, by 351 cities and towns, does little to foster uniform housing equity standards.

Clark Ziegler in MassBENCHMARK Journal vol.21 issue 1

For more information on the challenges of supply, affordability and equity, see the article. Clark Ziegler is the Executive Director of the Massachusetts Housing Partnership.

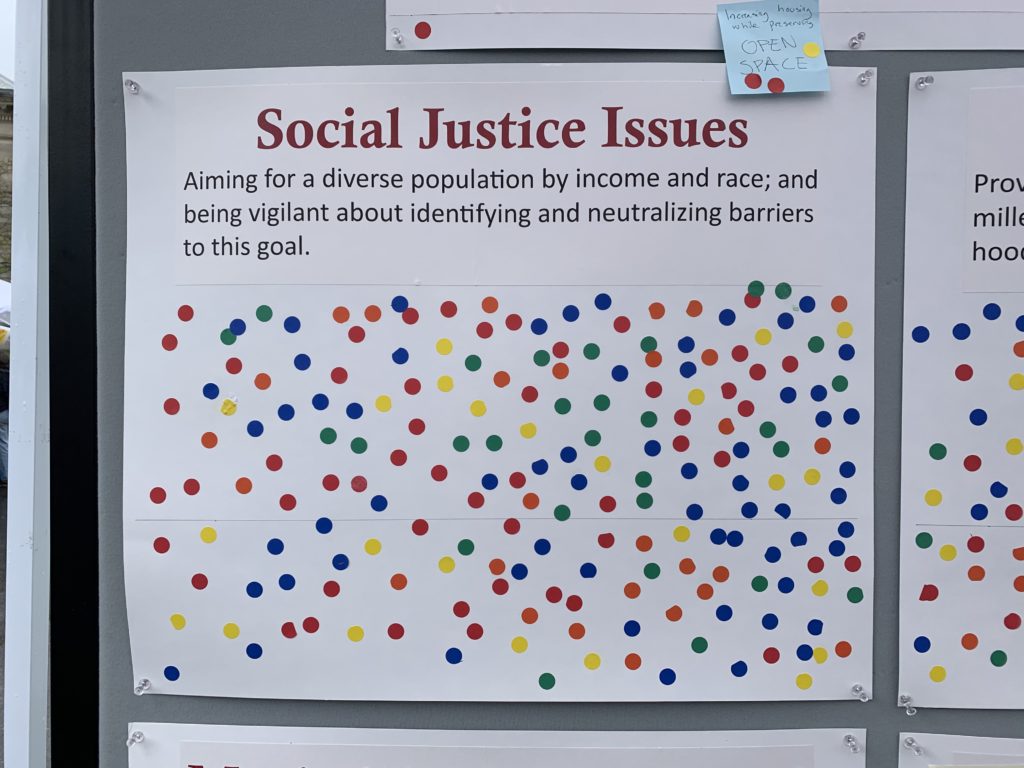

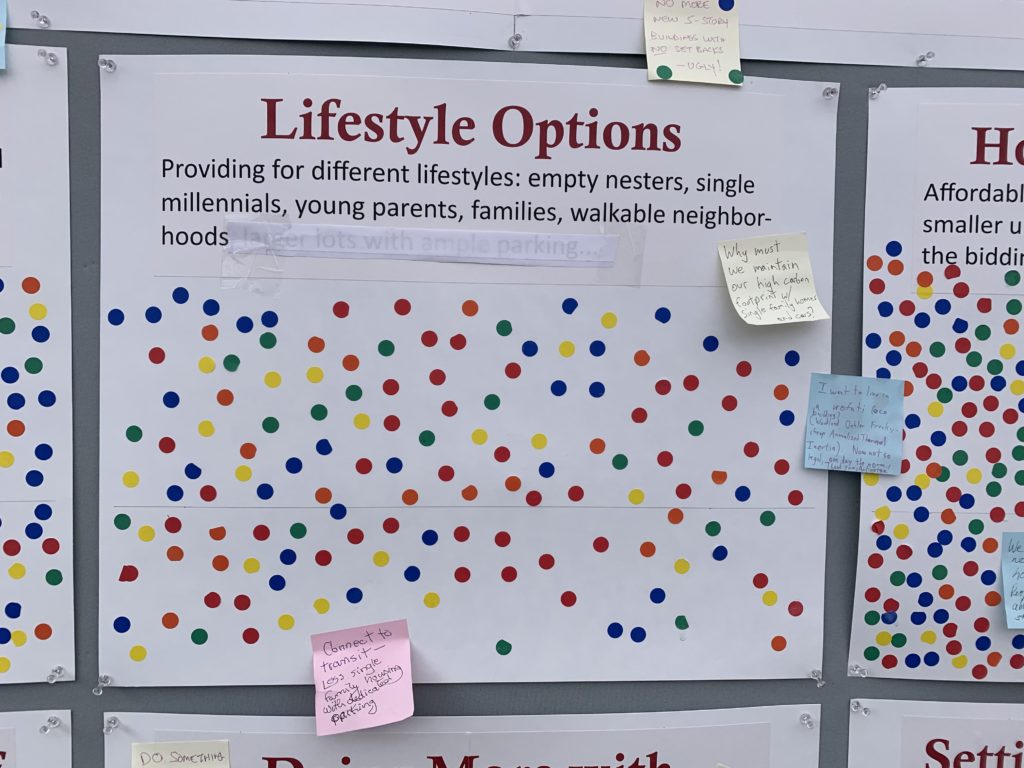

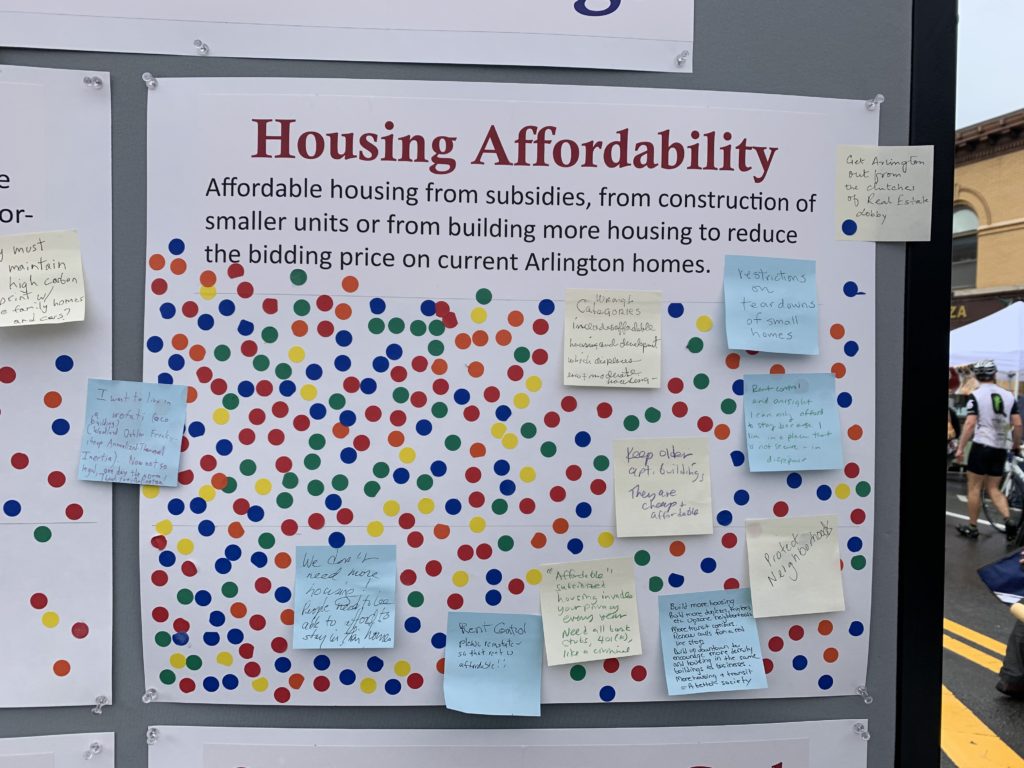

A portion of Envision Arlington’s town day booth was designed to spark a community conversation about housing. Envision set up a display with six poster boards, each representing a housing-related topic. Participants were given three dots and asked to place them on the topics they felt were most important. There were also pens and post-it notes on hand to capture additional comments. This post is a summary of the results. You could think of it as a straw-poll or temperature check on the opinions of town day attendees.

Aiming for a diverse population by income and race; and being vigilant about identifying and neutralizing barriers to this goal.

197 dots, plus a post-it note that reads “Increasing housing while preserving open space” (with three dots).

Providing for different lifestyles: empty nesters, single millenials, young parents, families, walkable neighborhoods.

149 dots and four post-it notes:

Affordable housing from subsidies, from construction of smaller units, or from building more housing to reduce the bidding price on current Arlington homes.

308 dots, with 10 post-it notes

This was clearly the topic that drew the most response. Arlington housing is expensive.

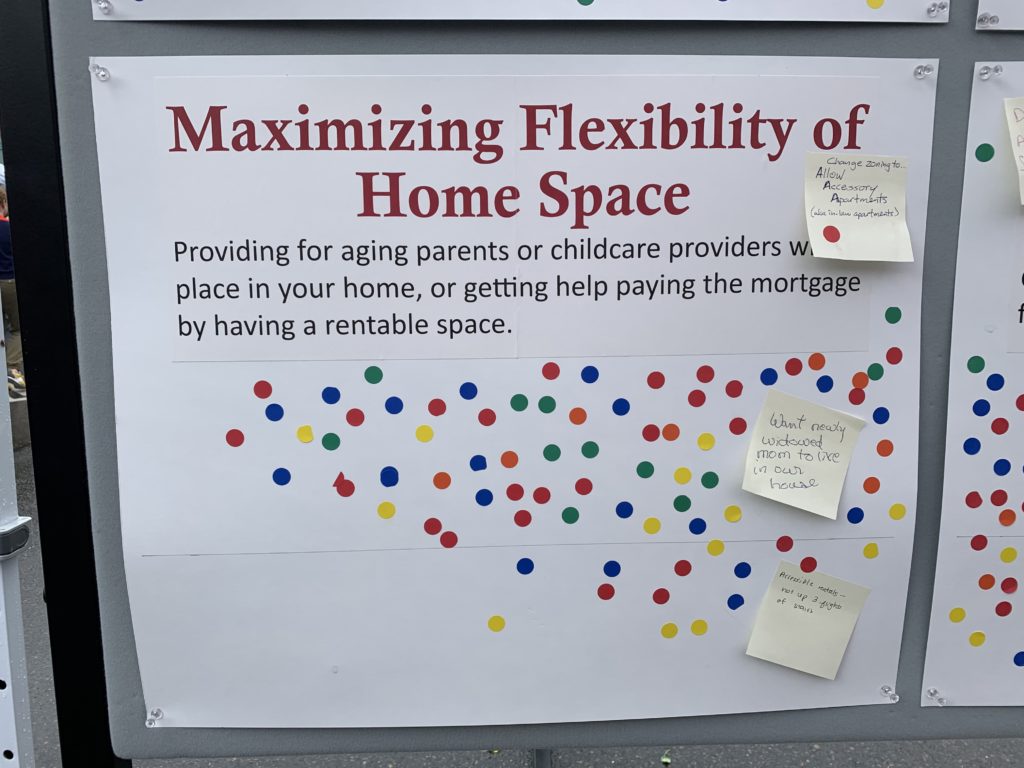

Providing for aging parents or childcare providers with a place in your home or getting help paying the mortgage by having a rentable space.

81 dots, and three post-it notes:

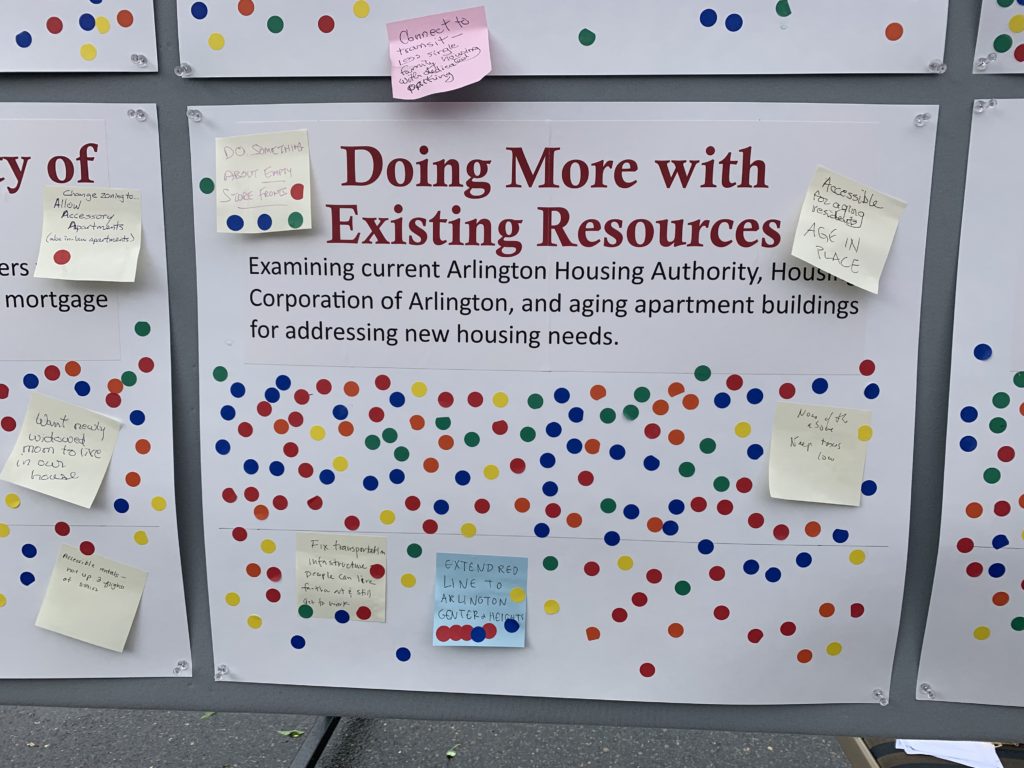

Examining current Arlington Housing Authority, Housing Corporation of Arlington, and aging apartment buildings for addressing new housing needs.

143 dots, and five post-it notes:

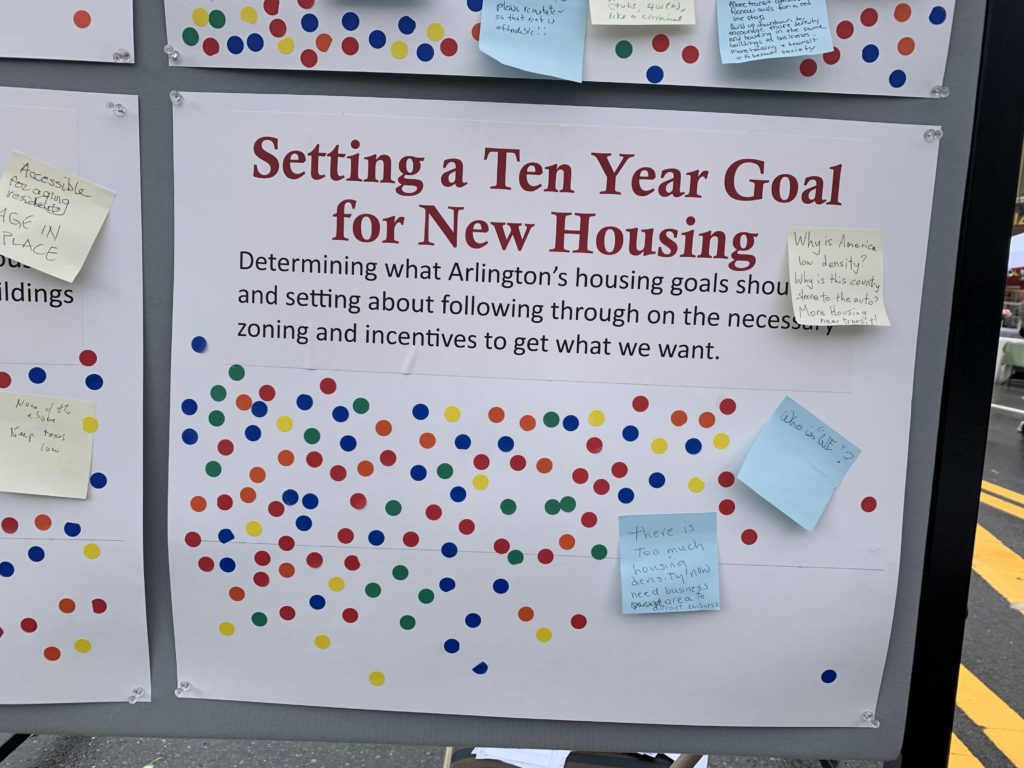

Determining what Arlington’s housing goals should be, and setting about following through on the necessary zoning and incentives to get what we want.

119 dots, and three sticky notes:

As noted earlier, the cost of housing seemed to be the main issue of concern. This is understandable: housing prices in Arlington (and the region in general) have been on an escalator ride up since about 2000 or so. That’s led to our current high cost of housing, and also to a form of gradual gentrification. When housing is more expensive than it was last year, a new resident in town has to make more money (or be willing to spend more on housing) than last year’s new resident.

I see at least two broad responses to this: one is to keep the status quo, perhaps returning to the inexpensive housing of decades past. The other is for more multi-family housing, and more transit-oriented development. It will be interesting to see how these dynamics play out in the future.

There’s also recognition of the importance of older “naturally affordable” apartment buildings. Arlington was very pro-growth in the 1950s and 1960s; that’s fortunate, because it allowed these apartments to be built in the first place. On the downside, we haven’t done a good job of allowing new construction into the pipeline during recent decades. Buildings depreciate, so a new building is worth more than one that’s ten years old, which is worth more than one that’s twenty years old, and so on. At some point, the old apartments are likely to be refurbished/upgraded, and they’ll become more expensive as a result.

This is only the beginning of the conversation, but at least we’re getting it going.

(presented by Adam Chapdelaine, Town Manager, to Select Board on July 22, 2019)

Since 1980 the price of housing in Massachusetts has surged well ahead of other fast growing states including California and New York. While the national “House Price Index” is just below 400, four times what an average house might have cost in 1980, a typical house in Massachusetts is now about 720% what it was in 1980. Median household income in the state has only increased about 15% during the same period. No wonder people in Arlington are feeling the stresses of housing costs if they want to live here and are feeling protective of the equity value time has provided them if they bought years ago.

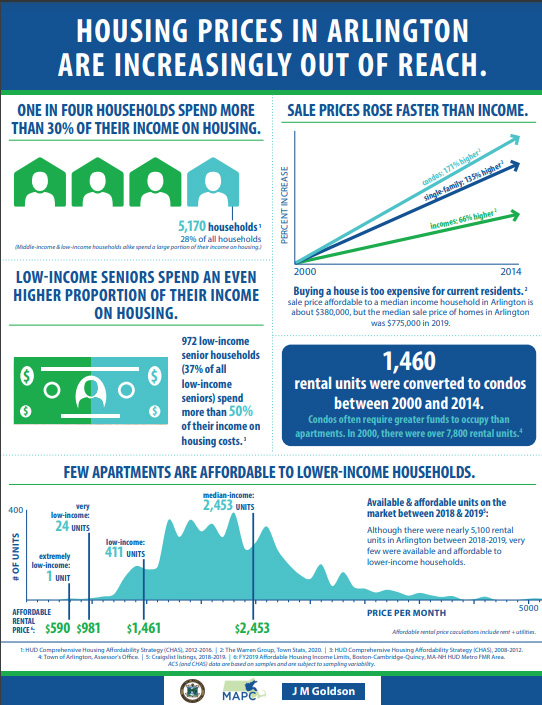

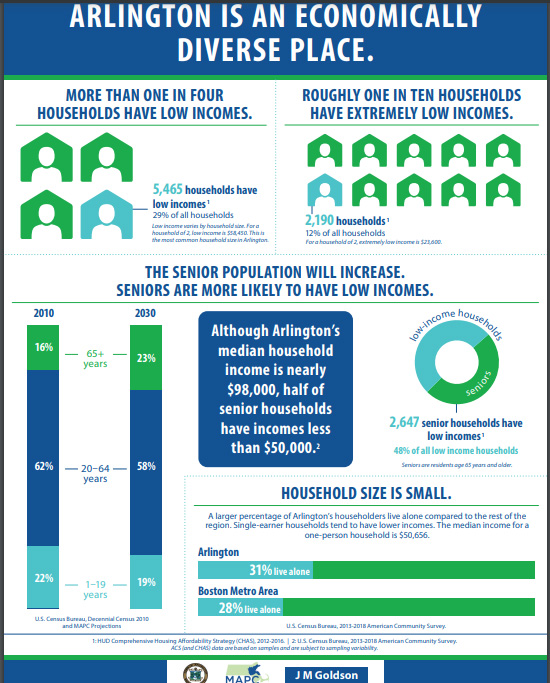

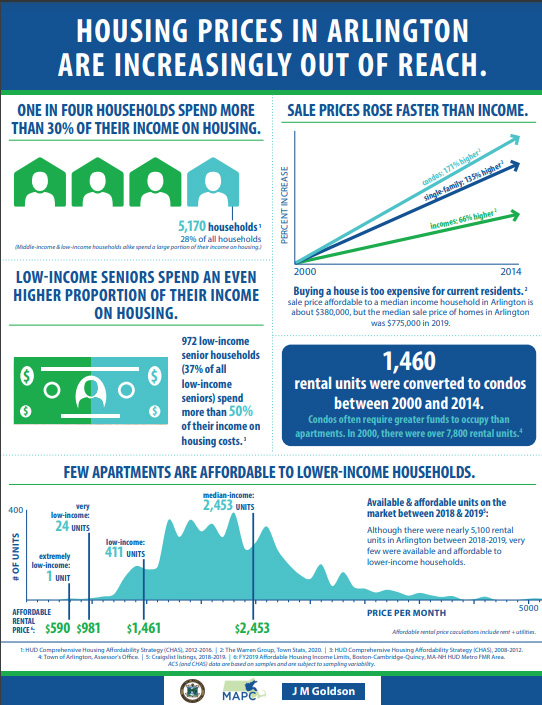

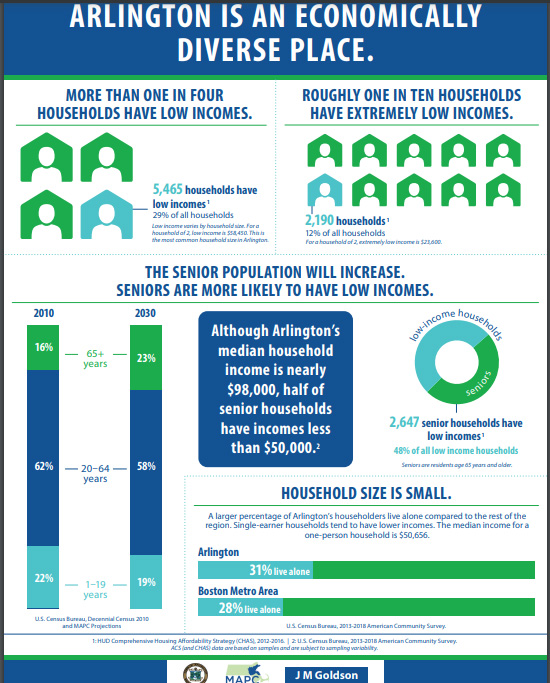

In response to concerns about zoning, affordable housing and housing density, the Town joined the “Mayors’ (and Managers’) Coalition on Housing” to address these growing pressures. This 12 page slide deck presentation outlines the key data points, the number of low and very low income households in Arlington, the rate of condo conversion that is absorbing rental units, etc.

Solutions are offered including:

• Amendments to Inclusionary Zoning Bylaw

• Housing Creation Along Commercial Corridor – Mixed Use & Zoning Along Corridor

• Accessory Dwelling Units – Potential Age & Family Restrictions

• Other Tools Can Be Considered That Are Outside of Zoning But Have An Impact on Housing

Chapdelaine’s suggested next steps are:

• Continued Public Engagement

• Town Manager & Director of DPCD Meet with ARB

• Select Board & ARB Hold Joint Meeting in Early Fall

• ARB Recommends Strategies to Pursue in Late Fall/Early Winter

The Select Board approved the suggested next steps and a joint ARB/ Select Board meeting should be scheduled in the near future.

Note from Reporter: As a community, Arlington has long prided itself on its economic diversity. With condo conversions, tear downs leading to “McMansions”, higher paid workers arriving in response to new jobs, etc., Arlington is at great risk of losing this diversity that has long enriched the community. Retirees looking to downsize and young people who have grown up in Arlington looking for their first apartment are finding it impossible to stay in town. Shop keepers and town employees are challenged to afford the rising housing costs. With a reconsideration of zoning along Arlington’s transit corridors, Arlington NOW has an opportunity to create new village centers, like those recommended in the recent STATE OF HOUSING report. These village centers along our transit corridors could be higher, denser but also offer the compelling visual design and amenities desired by people who want to walk to cafes, shops and public transit.

Equitable Arlington, along with City Life/Vida Urbana and the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, supports the legacy tenants of 840/846 Massachusetts Avenue in their resistance to rent increases of up to 50%. We urge the buildings’ owner, Torrington Properties, to continue negotiating an agreement with the tenants rather than pursue legal action likely to end in housing court. If more gradual increases are incompatible with Torrington’s business plan, we hope to see the sale of the property to the Housing Corporation of Arlington or another buyer who is committed to keeping the existing tenants in their homes.

The property, whose two larger buildings date to 1940 and 1963, faces Arlington High School, within easy reach of shopping and transit. It occupies one of relatively few spots in Arlington where people can live without a car. (Equitable Arlington and the MBTA Communities plan seek to encourage exactly this kind of housing.) Many of the middle- and lower-income tenants have been there for decades, including teachers, musicians, and some Section 8 voucher recipients. Some are immigrants with limited English. Laura Frost, who has lived there for 20 years, describes the apartments as “unofficial,” and therefore legally unprotected, affordable housing. Erica Schwarz, executive director of the Housing Corporation of Arlington, concurs: “There are so few places where low-income tenants are in units that aren’t restricted.”

When Torrington Properties bought the buildings in 2019, it did not raise rents right away. Instead, the company pursued a familiar strategy of remodeling apartments when tenants moved out and then marketing them as “luxury” units. More recent arrivals are paying typical market rents. Of the longtime residents, several have left because they were worried about being pushed out to make way for more remodeling and steep rent increases, says Frost, who leads the tenants’ association. All have been tenants at will since Torrington bought the property, with their rents not rising but also not guaranteed by 12-month leases. In November 2022, she says, Torrington distributed a list of target rents for all of the units. A few months later, it informed legacy tenants, then about 20 in number, that they needed to either sign leases at the new rates or move out.

“Our position was never ‘You can’t raise rents ever,’” says Frost, who recognizes that Torrington can legally set rents at any level. Working with City Life/Vida Urbana, she hoped for an agreement for more gradual rent increases, like the one Torrington had just reached with tenants near Forest Hills in Boston. By last spring, however, negotiations had broken down. A rally she organized in September drew Reps. Garballey and Rogers. In February, Torrington sent the legacy tenants notices to quit. We are encouraged that negotiations have since resumed. At the same time, we support a more sustainable option for these tenants and anyone who lives there in the future, as well as Arlington as a whole: a commitment, perhaps by a new owner, to keeping some units affordable in the long term.

Schwarz, of the Housing Corporation of Arlington, has discussed purchasing the property from Torrington, which named a price she describes as “a few million dollars more” than HCA can offer. She has been exploring alternative ways to structure a purchase. This would include drawing on the Town of Arlington’s ARPA funds, as well as seeking mission-aligned equity partners for the project under a “mixed income” model. This would not displace any current tenants, but would, over time, provide a very high percentage of affordable units at a range of income levels, while also providing middle-income and market rate units.

Equitable Arlington supports common-sense reforms that allow for more housing options and tenant protections for current and future Arlington residents. We support increased funding for affordable housing, both through the Affordable Housing Trust Fund and state and federal subsidies, and a wider range of housing choice for every income level and every life stage. We also champion housing that is sustainable, equitable, and accessible, including locating additional housing near public transportation, all of which we believe will make Arlington an even more welcoming community.

Beginning last July, 2020, the Town of Arlington and community groups in the town are sponsoring a number of webinars and zoom conversations addressing the need for affordable housing programs in Arlington. Several factors contribute to the Arlington housing situation: diversity of housing types, prices, diversity of incomes, availability of housing subsidies, rapid growth in property values that greatly exceed the rate of growth of income.

But racism, both historic and current, continues to stand out as a significant force contributing to the difficult housing situation.

One of the first public discussion in the Town on this subject was organized by Arlington Human Rights Commission (AHRC) on July 8, 2020. View it here: