The City of Somerville estimates that a 2% real estate transfer fee — with 1% paid by sellers and 1% paid by buyers, and that exempts owner-occupants (defined as persons residing in the property for at least two years) — could generate up to $6 million per year for affordable housing. The hotter the market, and the greater the number of property transactions, the more such a fee would generate.

Other municipalities are also looking at this legislation but need “home rule” permission, one municipality at a time, from the state to enact it locally. Or, alternatively, legislation could be passed at the state level to allow all municipalities to opt into such a program and design their own terms. This would be much like the well regarded Community Preservation Act (CPA) program that provides funds for local governments to do historic preservation, conservation, etc.

This memorandum from the City of Somerville to the legislature provides a great deal of information on the history, background and justification for such legislation.

House bill 1769, filed January, 2019, is an “Act supporting affordable housing with a local option for a fee to be applied to certain real estate transactions“.

COMMENT:

KK: This article suggests Arlington may be likely to pass a real estate transfer tax: https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/12/19/boston-one-step-closer-to-a-luxury-real-estate-transfer-tax/

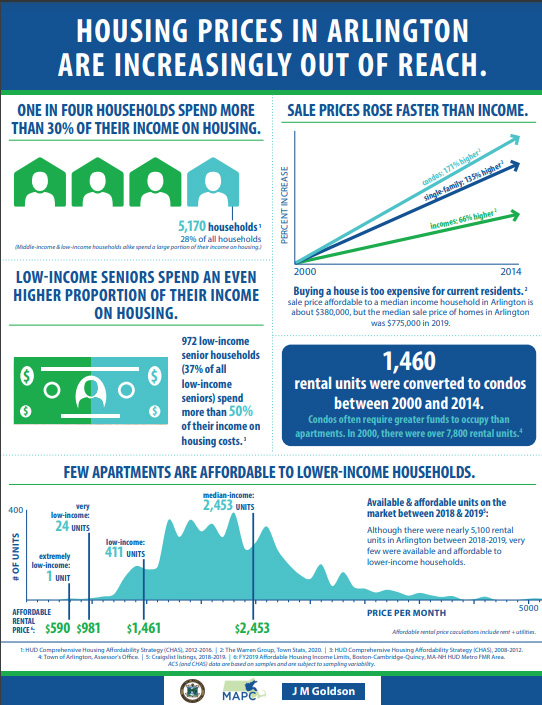

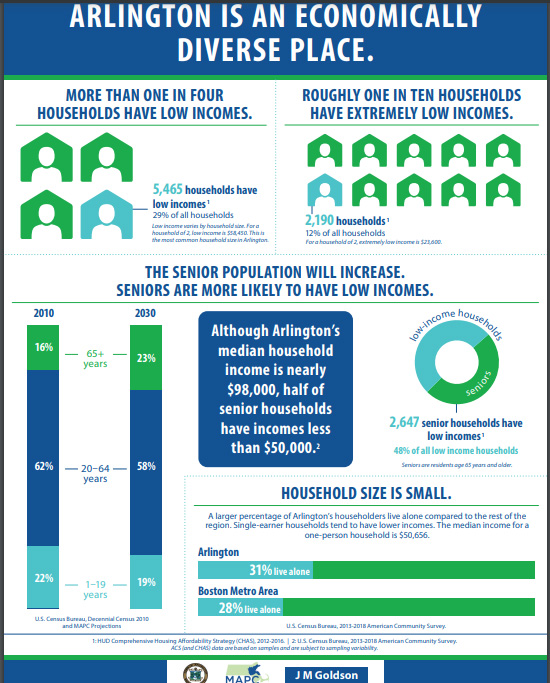

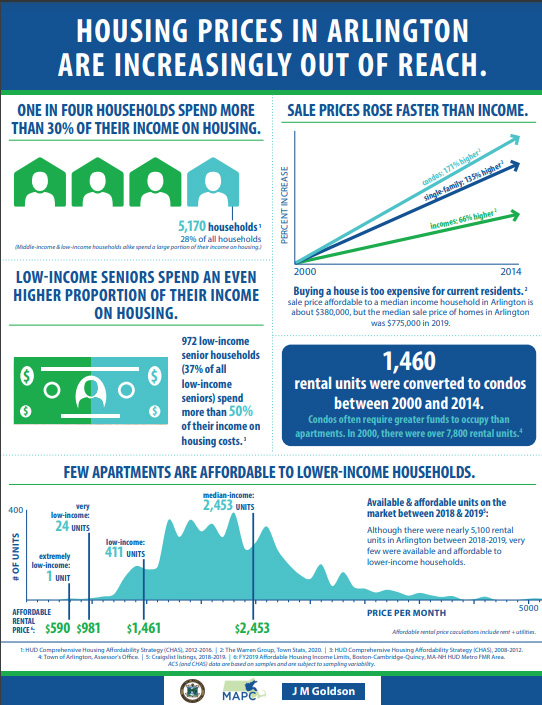

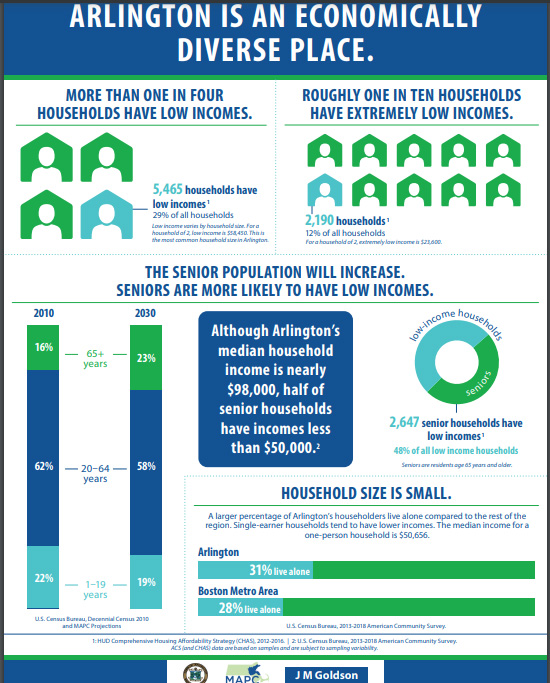

In a 2019 study, MAPC found that:

This study raises important questions about the wisdom of continuing to commit large sections of the land area of our municipalities to be on reserve for parking cars. Such extra space could be used to benefit the open space, environmental sustainability and the need for more housing.

Text of Warrant Article 8: (To be considered at Special Town Meeting (Virtual), Mon. 11/16/20 at 8:00 p.m.)

“ARTICLE 8 ACCEPTANCE OF LEGISLATION/BYLAW AMENDMENT/ MUNICIPAL AFFORDABLE HOUSING TRUST FUND

To see if the Town will vote to accept Massachusetts General Laws c. 44 § 55C, to authorize the creation of a Municipal Affordable Housing Trust Fund to support the development of affordable housing in Arlington, establish a new bylaw for the administration of same; or take any action related thereto. (Inserted by the Select Board)”

What will it do? How will it work?

A Proactive Step to Address Housing Affordability. With a municipal affordable housing trust, Arlington will join more than 113 Massachusetts municipalities that have formed a housing trust fund to support a proactive strategy for building housing affordability. The Trust is a small step the Town can take to more proactively address the housing affordability crisis that challenges many of our current residents and makes Arlington increasingly inaccessible to new residents. Creating affordable housing can also be a strategy for maintaining or increasing diversity.

Ability to Act Quickly.

A primary benefit of a housing trust is to enable the Town to act quickly to support or participate in transactions that increase or preserve affordable housing in Arlington. Without a Trust, the Town does not have the flexibility or agility to act quickly. Following are some examples, though there are many other ways that trusts can and do advance housing affordability:

• Financing the acquisition and/or development of market properties for conversion to affordable housing by a nonprofit developer;

• Purchasing an existing affordable home to ensure resale to another low income buyer, or purchasing a market rate home to create an affordable homeownership opportunity;

• Providing flexible financing to increase the number of affordable units or reduce income levels in existing or new projects that include affordable housing.

Developing a Housing Trust Strategy Over Time.

The strategies to be pursued by the Trust would be set forth by the Trustees in a plan or proposal(s) they would lay out after they are appointed, most likely after/through a process of public engagement. The specific strategies are, deliberately, not part of the warrant article or the Bylaw proposed for adoption. This allows the Town the flexibility to set and modify the Town’s housing strategies over time, in a manner that is responsive to the public and its elected representatives. The Bylaw requires the strategy or plan, and most major Trust decisions, to be approved by the Select Board, and Town investments in the Trust would still require Town Meeting approval.

Funding the Affordable Housing Trust Fund.

Creating affordable housing requires substantial subsidy. The Trust’s ability to cause more affordable housing to be created or preserved in Arlington will be directly related to the availability of resources to fund it and leverage additional state and federal resources. The vote before the Special Town Meeting this fall will not provide any funding for the Trust.

While it is anticipated that the Trust might receive initial funding via a grant of Community Preservation Act funds from the CPA Committee, to increase our impact, more resources will be needed.

How Other Communities Fund Their Housing Trust Funds.

The Community Preservation Act is the most common source of funding, but the most impactful trusts tend to have a variety of funding sources that result in a steady flow of financial resources into the Trust. Other municipalities have tapped into a variety of additional sources, including inclusionary zoning payments, federal HOME funds, voluntary/negotiated developer payments, proceeds from sale of tax foreclosed or other Town-owned properties, cell tower payments, cannabis-related revenue, short-term rental fees, fees for managing housing lotteries, sale of bonds, general municipal funding, and private donations. Many also donate excess town property to their housing trust for sale and redevelopment as affordable or mixed income housing. More recently, a number of cities and towns have proposed home rule petitions that would allow them to impose a small fee on the transfer of real property to fund their housing trusts, and there is state legislation proposed to authorize cities and towns to impose such transfer fees without sending a Home Rule Petition to the state legislature.

Building Trust Resources Through a Transfer Fee.

The Housing Plan Implementation Committee originally recommended that Town Meeting adopt a bylaw creating a housing trust and create a funding source for it by voting to authorize the filing of a home rule petition to impose a modest real estate transfer fee. Although the Select Board elected to defer consideration of the transfer fee until 2021, such a fee is attractive to many, because it would be borne only by those selling their Arlington homes or properties, and because it provides a mechanism to capture a very small portion of the extraordinary equity increase that Arlington property owners have realized over many years due to regional market forces. The details of such a fee are important and merit further discussion, but it presents a promising potential revenue source to empower the Trust to be proactive.

The Process.

The article in front of the Special Town Meeting would start the process of creating a municipal affordable housing trust. Once approved by Town Meeting the Affordable Housing Trust Bylaw would be submitted to the Attorney General to certify its consistency with the state law governing housing trusts within 90 days. Once so certified, the Town Manager will appoint trustees, including at least one member of the Select Board. Once these appointments are confirmed by the Select Board, the Trustees themselves would lead the process of proposing an initial set of goals and strategies for the Trust to implement, after approval by the Select Board.

Financial Stability & Accountability.

The Trust will be governed by the MAHT law passed in 2005 that specifies powers and limitations for trusts of this type. The proposed Bylaw has been reviewed and modified pursuant to suggestions of the Finance Committee to ensure accountability and financial stability. The Trust will be managed by the Treasurer, will be audited annually, will have legal and practical limitations on its borrowing capacity, and will not have the power to pledge the full faith and credit of the Town.

To learn more about municipal affordable housing trusts, refer to the MHP Municipal Affordable Housing Trust Fund Guide, v.3

******

This information was prepared by Karen Kelleher, Arlington Town Meeting Member, Precinct 5, Member, Arlington Housing Planning Implementation Committee and Executive Director, LISC Boston ( Local Initiative Support Corporation)

(published June, 2019)

To solve the extraordinarily large deficit in housing for the greater Boston region, over 180,000 units of new housing should come on line in the next few years. This deficit is the result of a rapid expansion in in-migration due to new job creation, with no commensurate increase in housing production for the people taking those new jobs.

The report concludes that zoning is a primary culprit in restricting the development of an adequate housing supply, creating a “PAPER WALL” keeping out newcomers. The cost of this inadequate supply is a huge demand for housing which, in turn, bids up the price for available housing. The following “culprits” are considered: inadequate land area zoned for multi-family housing; low density zoning; age restrictions and bedroom restrictions; excessive parking requirements; mixed use requirements and approval processes. Alternative zoning models are suggested.

Elements such as “Approval Process”, “Mixed Use”, “Village Centers vs Isolated Parcels” and “Building Up or Building Out” are considered.

Researcher Amy Dain reports on two years of research into the regulations, plans and permits in the 100 cities and towns surrounding Boston. The research was commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance and funded collaboratively with: Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association, Home Builders & Remodelers Association of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Association of Realtors, Massachusetts Housing Partnership, MassHousing, and Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

For the full report see: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

For a power point slide presentation see: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/04/DainZoningMFPresentationShare2019.pdf

For the Executive Summary see: https://equitable-arlington.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/June-2019-Multi-Family-Housing-Report_Executive-Summary.pdf

by Alexander vonHoffman, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, February 2006

The case study shows that in the 1970s the Town of Arlington completely abandoned its policy of encouraging development of apartment buildings—and high-rise buildings at that—and adopted requirements that severely constricted the possibilities for developing multifamily dwellings. Although members of the elite introduced the new approach, they were backed by rank-and-file citizens, who took up the cause to protect their neighborhoods from perceived threats.

The report outlines an intentional effort using land use and planning tools like zoning and building approvals, to exclude those with less desirable income or racial characteristics from residing in Arlington. Additional perspectives on Arlington’s exclusionary zoning efforts during this period are reported here.

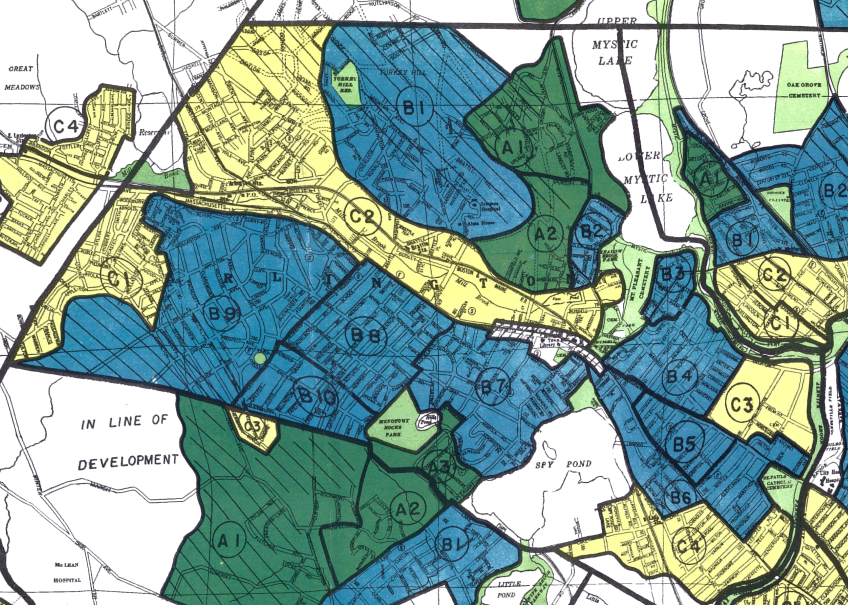

In the 1930’s the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation of America (HOLC) created actuarial maps of the United states. These maps were color coded — Green, Blue, Yellow, and Red — to reflect the amount of “risk” associated with home loans in those areas. The colors corresponded to “Best” (green), “Still Desirable” (blue), “Definitely Declining” (yellow), and “Hazardous” (red). Being in a green area made you likely to secure a federally-insured home mortgage, something that was effectively unavailable to red areas. Red areas were often associated with black populations, and these maps are where the term “redlining” comes from.

Here’s an HOLC map of Arlington, courtesy of the University of Richmond’s mapping inequality project.

Note that Arlington does not have any “Hazardous” (red) areas; 68% of the town fell into the top two grades, meaning that we were generally a safe bet as far as federal mortgage insurers were concerned. To the extent that the HOLC preferred white communities, Arlington seems to have fit the bill. According to US census data.

Today, Arlington is about 84% white. But during the time that mortgage approvals were based on the HOLC maps — the mid 1930’s through the mid 1960’s — we certainly qualified as an overwhelmingly (> 99%) white community.

Arlington had four yellow-lined (“definitely declining”) areas; about 32% of the town. C1 (on the western edge of town) was noted for an “infiltration of Jews”, a “heavy concentration of relief families”, and hilly terrain which was “not conducive to good development”. But it had good schools and a nice area along Appleton St. C2 (along Mass Ave and Mill Brook) was noted for “obsolescence” with “business and housing mixed together” and “railroad tracks through [the] neighborhood”. There was an infiltration of lower-class people, a moderate number of relief families, and “little possibility of conversion of properties to business use”.

C3 (East Arlington, around the present location Thompson School and Menotomy Manor) was noted for “Obsolescence, poor reputations” and “foreign concentration”. There was an “infiltration of foreign [residents]” and a “heavy concentration of relief families”. On the positive side, there were “a few small farms in this section of high grade development of the ground [which] may be anticipated in the early future with modest houses”.

Finally, C4 (around Spy Pond, and near the Alewife T station) was “obsolescent”, with an infiltration of foreign families, and a moderately heavy concentration of relief families. The HOLC noted that “Houses East of Varnum Street [and] south of Herbert Road are built on low ground and many have damp basements which makes them difficult to keep occupied”.

That’s what the HOLC saw as the declining side of Arlington: Jews, foreigners (mostly Italian), relief families, obsolescence, damp basements, and proximity to the Boston-Maine railroad.

Exercise for the reader. Arlington has five public housing projects: Drake Village, Winslow Towers, Chestnut Manor, Cusack Terrace, and Menotomy Manor. What HOLC colors are associated with our public housing?

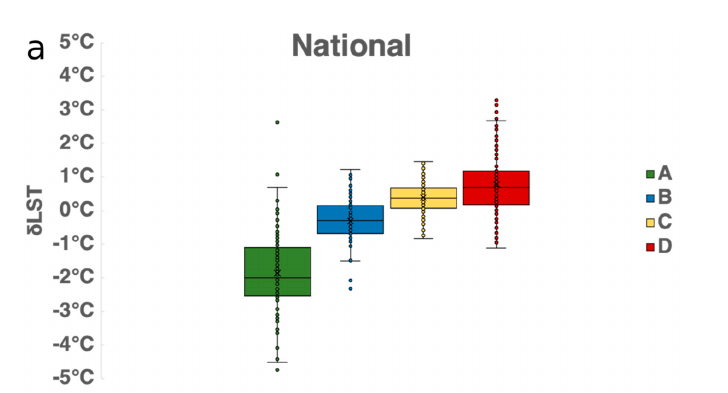

Buildings last for decades, and effects of the HOLC’s underwriting policies are still with us today — sometimes in unexpected ways. A 2020 paper called “The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: A Study of 108 US Urban Areas” examined 108 communities, and tried to determine if there was a relationship between redlined areas and urban heat islands. Nationwide, this is what they found:

LST stands for “land surface temperature” and shows how different HOLC risk categories compare to the overall temperature of a region. Green areas tend to be cooler, with less paved surface, more extensive tree canopies, and buildings with reflective exteriors. Red areas are warmer with more paved surfaces, less tree canopy, and building exteriors that absorb and release heat (e.g., brick and cinderblocks). While the degree varies across different parts of the country, the general trend is the same: as one goes from green to red, the surface temperature goes up. Formerly-redlined areas are far more likely to contain heat islands.

Exercise for the reader. Are there heat islands in Arlington? What (HOLC) color are they?

As the global temperature warms, Arlington (like many other communities) will have to contend with heat islands. The treatment is likely to be area-specific, following patterns laid out in the HOLC’s maps from the early-20th century.

Prof. Christophe Reinhardt runs the MIT Sustainable Design Lab. On Nov. 25, 2019 he gave a very interesting presentation, including talk and slides, that shows a pathway to make more housing, all kinds of housing, and greater housing density both more palatable in Arlington, and actually desirable. He also stressed the importance of paying attention to housing now in order to meet the climate change challenge. Charts (starting about 10 min in) show how drastically we need to reduce our carbon footprint to reach net zero by 2050. Buildings today account for about 40% of our carbon emissions world wide. What we build today will likely be around through 2050.

Paying attention to housing design is important to create a sustainable environment.

Here is the link for the Reinhardts talk and slide show:

http://scienceforthepublic.org/energy-and-resources/designing-sustainable-urban-development

or see it on youtube: https://youtu.be/YAeCvUZmUrI

He uses research, drawn from around the world and locally, to show what measurable attributes make local communities desirable to live in and what attributes of housing make residents happy.

Key attributes for success (slide is at about 18:15 min. in presentation):

1. Economic opportunities (proximity to work opportunities)

2. High quality living (daylight access for buildings, streets, walkable, mixed use, micro-units, vibrant public spaces, organic food, fitness opportunities)

3. Sustainability (comfortable work and play and living spaces, resource efficiency)

The presentation was arranged by the Robbins Library. It was developed and recorded by Science for the Public as part of it’s lecture series.

For more information on sustainability and cities, cities and local municipalities are beginning to recognize the important linkages between urban resiliency, human well-being, and climate change mitigation and adaptation activities. https://news.mongabay.com/2019/11/how-cities-can-lead-the-fight-against-climate-change-using-urban-forestry-and-trees-commentary/ Courtesy of Science for the Public Interest Weekly News Roundup.

(For more opportunities to learn about sustainability, buildings and cities, sign up for the FREE MITx “Sustainable Building Design” online course which starts January.)

This is our national challenge for the next 25 years, according to Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, Executive Vice President/Chief Strategy Officer for MassDevelopment, the Commonwealth’s economic development and finance authority.

Fuhrer prepared this slide presentation for a meeting with regional affordable housing experts and developers in November, 2020. Part 1 looks at projections for the financial markets and issues in tax exempt financing and how such financing can help provide more affordable housing for poor people.

Part 2, starting on slide 13, looks more explicitly at the sources of racially based economic inequality in the US. The study’s author spent decades working with the Federal Reserve and determines that research shows the scourge of Black poverty compared to other races is not due to education but rather to land use, zoning and housing finance decisions set in place by governmental agencies that have intentionally limited access to equity building opportunities for Black Americans.

Slide 18 shows the U.S. Black population in Boston region has a household median net worth of about $0. While the white population in the region has an estimated net worth of $247,000 per household.

Changing landuse and zoning policies as well as using tax exempt financing are some of the ways to remedy this long standing problem. Additional causes are listed on slide 20:

Key examples:

• Post Civil War “reconstruction” an embarrassing string of broken promises and abuse

• Social Security and unemployment insurance in the 1930s excluded domestic and agricultural workers

(65% of black workforce excluded, versus 25% of white

• Debate about whether it was intentionally discriminatory

• Housing assistance in the 1940s (e.g. Levittown written clause excludes black homeowners)

• The GI bill post WWII a tiny fraction went to black soldiers

• Housing policy post 1950s

• Welfare reforms of the 1990s

• Current: Education spending disparities; criminal justice disparities (the “War on Drugs”); policing disparities; voter registration restrictions

See the full slide presentation here.