Many issues are under discussion as a result of these proposed zoning Articles. Issues include: housing affordability, the diversity of housing and incomes in Arlington, environmental concerns and sustainability, tax burdens or tax savings potentially resulting from growth, the risk of postponing the decisions, and the image of Arlington as a community that values diversity and equitability. This one page “fact sheet” attempts to address many of these issues and concerns.

Related articles

The citizen participation process including presentations, discussions, public hearings, letters and comments has been long and arduous. The issues are complicated and sometimes feelings run high. In such situations, there can be a feeling that citizens have not been heard. This document, “Guide to Zoning Amendments Related to Multifamily Uses and Mixed-Use“, summarizes many of the issues that have been raised and the changes that have been made in the zoning Articles as a result of the citizen participation in the public review process. Citizens have been heard.

State Senator Cindy F. Friedman has written a letter to Town Meeting Members supporting Warrant Article 12 and a meaningful MBTA Communities Plan. She writes:

We all want Arlington and Massachusetts to remain welcoming, accessible places to live. In addition to our deficit of housing, I recognize the importance of encouraging smaller, more sustainable housing in walkable areas. Arlington’s Warrant Article 12 will provide a meaningful framework for making progress in these areas. The problems we are experiencing now —out of reach housing prices for new construction and existing homes — exacerbate the crisis and are seriously threatening the economic vibrancy of our communities.

To read Friedman’s full letter, click here for the PDF.

Two weeks ago, I helped to organize a precinct meeting for residents and town meeting members. During the meeting, we got into a discussion about public open spaces, how the town funds their upkeep, and whether having more commercial tax revenue might provide additional funding for parks and recreation.

As I discussed in an earlier post, only about 5.6% of Arlington’s is zoned for commercial uses, and that limits the amount of commercial property tax revenue we can generate. Commercial property tax revenue is sometimes referred to as “CIP”, which stands for “Commercial, Industrial, and Personal”. Commercial and Industrial refer to property taxes on land and buildings that are respectively used for commercial and industrial uses. Personal tax is tax on the value of equipment that’s owned and used by a business for the purpose of carrying out whatever their business is. This could include things like desks, display fixtures, cooking equipment, fork lifts, and the like.

In 2020, Arlington’s CIP levy was 5.45%, meaning that 5.45% of our property tax revenue came from Commercial, Industrial, and Property tax revenue. Breaking this down further, 4.2% was commercial ($5,562,528 tax levy), 0.2% was industrial ($278,351 tax levy), and 1.1% was personal ($1,423,117 tax levy). The town’s total 2020 tax levy was $133,350,155. This data comes from MassDOR’s Division of Local Services, and I’ll provide more specific sources in the “References” section of this post.

A CIP levy of 5.45% is low (compared with other communities in the commonwealth), and occassionaly folks like to talk talk about how to raise it. Which is to say, we about how to raise the ratio of commercial to residential taxes. I moved to Arlington in 2007, when our CIP levy was 5.37%. This increased in subsequent years, peaking at 6.26% in 2013, and has been gradually decreasing since. Recall that 2008 was the year the housing market crashed, and the “great recession” began. The value of Arlington’s residential property fell, but the value of business properties was relatively stable in comparison. Thus, our CIP percentage got a boost for a couple of years.

Tax levies (the amount of tax collected) are a direct reflection of the tax basis (the assessed value of property). I’m going to shift from talking about the former to talking about the latter, because that will lead nicely to a discussion about property wealth. Which is to say, the aggregate value of property assessments in town.

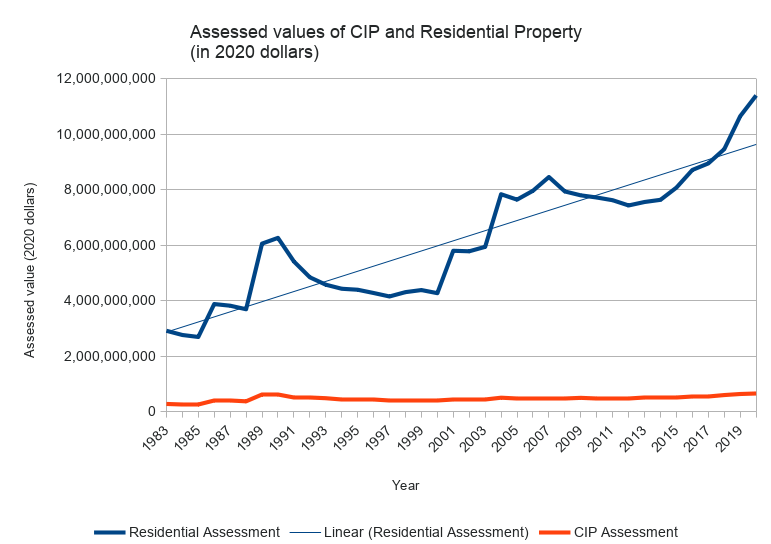

Here’s a chart showing Arlington’s net CIP and residential property values, from 1983–2020, adjusted to 2020 dollars. (This is similar to the chart that appears on page 102 of Arlington’s Master plan, but for a longer period of time).

Generally speaking, the value of Arlington’s residential property has appreciated considerably, and there’s a widening gap between our residential and CIP assessments (in terms of raw dollars). Because the gap is so large, it’s helpful to see it on a log scale.

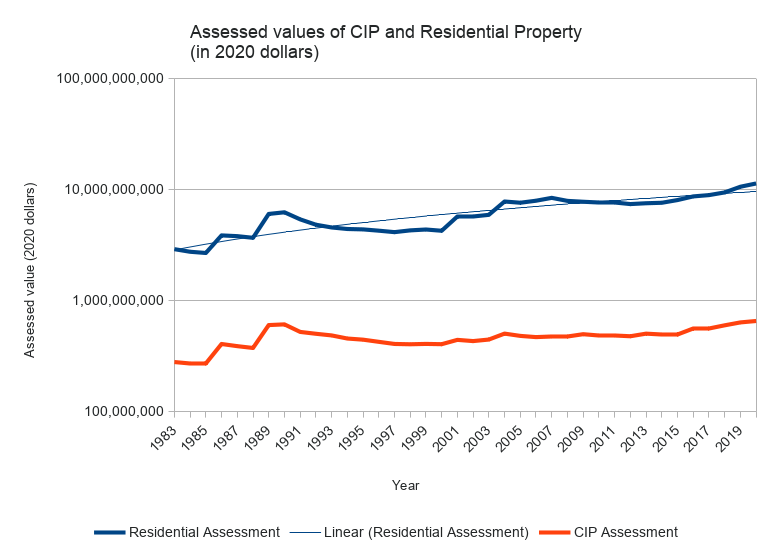

Viewed this way, the curvatures are generally similar, but residential property wealth is rising faster than business property wealth.

In summary, there are three reasons why our CIP is as low as it is: (1) a limited amount of land where one can run a business, (2) the value of residential property is appreciating faster than the value of business property, and (3) occasionally business properties are converted to residential (perhaps with the residential property being worth more than the former business property). That’s not to say we can’t improve the commercial tax base. We can, but we will have to think about what and where, and how to compete with a generally competitive residential market.

References

- MassDOR Division of Local Services reports

- DOR Query Tool for Municipal Property Assessments

- DOR Query Tool for Municipal Tax Levies

- Spreadsheet of Arlington Property Assessments, 1983–2020. Data obtained from MassDOR, with calculations added to adjust for inflation.

- Spreadsheet of Massachusetts Property assessments for 2020. Data obtained from MassDOR.

(Updated 7/2/2020, to add log scale graph and revise conclusion.)

Article 1 in a series on the Arlington, MA master planning process. Prepared by Barbara Thornton

Arlington, located about 15 miles north west of Boston, is now developing a master plan that will reflect the visions and expectations of the community and will provide enabling steps for the community to move toward this vision over the next decade or two. Initial studies have been done, public meetings have been held. The Town will begin in January 2015 to pull together the vision for its future as written in a new Master Plan.

In developing a new master plan, the Town of Arlington follows in the footsteps laid down thousands of years ago when Greeks, Romans and other civilizations determined the best layout for a city before they started to build. In more recent times, William Penn laid out his utopian view of Philadelphia with a gridiron street pattern and public squares in 1682. Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant developed the hub and spoke street plan for Washington DC in 1798. City planning started with new cities, relatively empty land and a “master builder” typically an architect, engineer or landscape architect commissioned by the land holders to develop a visionary design.

In the 1900’s era of Progressive government in America, citizens sought ways to reach a consensus on how their existing cities should evolve. State and federal laws passed to help guide this process, seeing land use decisions as more than just a private landowner’s right but rather a process that involved improving the health and wellbeing of the entire community. While the focus on master planning was and still is primarily physical, 21st century master planners are typically convened by the local municipality, work with the help of trained planners and architects and rely heavily on the knowledge and participation of their citizenry to reflect a future vision of the health and wellbeing of the community. This vision is crafted into a Master Plan. In Arlington the process is guided by Carol Kowalski, Director of Planning and Community Development, with professional support from RKG Associates, a company of planners and architects and with the vision of the Master Planning advisory committee, co-chaired by Carol Svenson and Charles Kalauskas, Arlington residents, and by the citizens who share their concerns and hopes with the process as it evolves. This happens through public meetings, letters, email, and surveys. The most recent survey asks residents to respond on transportation modes and commuting patterns

We all do planning. Starting a family, a business or a career, we lay out our goals and assume the steps necessary to accomplish these goals and we periodically revise them as necessary. The same thing is true for cities. Based on changes in population, economic development, etc. cities, from time to time, need to revise their plans. In Massachusetts the enabling acts for planning and zoning are here http://www.mass.gov/hed/community/planning/zoning-resources.html. The specific law for Massachusetts is MGL Ch. 41 sect. 81D. This plan, whether called a city plan, master plan, general plan, comprehensive plan or development plan, has some constant characteristics independent of the specific municipality: focus on the built environment, long range view (10-20 years), covers the entire municipality, reflects the municipality’s vision of its future, and how this future is to be achieved. Typically it is broken out into a number of chapters or “elements” reflecting the situation as it is, the data showing the potential opportunities and concerns and recommendations for how to maximize the desired opportunities and minimize the concerns for each element.

Since beginning the master planning process in October, 2012, Arlington has had a number of community meetings (see http://vod.acmi.tv/category/government/arlingtons-master-plan/ ) gathering ideas from citizens, sharing data collected by planners and architects and moving toward a sense of what the future of Arlington should look like. The major elements of Arlington’s plan include these elements:

1. Visions and Goals http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19829

2. Demographic Characteristics http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19838

3. Land Use http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19834

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19825

4. Transportation http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19830

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19822

5. Economic Development http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19837

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19828

6. Housing http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19835

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19826

7. Open Space and Recreation http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19832

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19824

8. Historic and Cultural Resources http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19836

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19827

9. Public Facilities and Services http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19831

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19823

10. Natural Resources

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19824

The upcoming articles in this series will focus on each individual element in the Town of Arlington’s Master Plan.

The cost of building a residential unit, single or multi-family, correlates directly, if not precisely, with its cost to resident tenants or owners. The following study and data (using Assessor’s data) demonstrates that higher density housing is more affordable than single-family housing. Whether you look at the median cost of all housing across the Town or the unit costs of the newer, more expensive, apartments built in the last decade, density yields lower prices. The town wide median is $438,900 per unit.

The newest projects (420-440 Mass Ave., Brigham Square and Arlington 360) range from $249k per unit to $412K per unit. These three developments alone contributed 414 new units of housing to the Town.

Discussions of “affordability” represents a spectrum of terms. Units can be affordable because zoning and market conditions allow the units to be built for less money than a single family home. Or they can be affordable because the builder has received subsidies that reduce the cost. Or they can be affordable, as in the case of inclusionary zoning, because the permission to build is contingent on at least some of the units being “permanently” (99 years) available to qualified tenants or buyers based on legal restrictions.

It’s New Year’s eve and I’m determined to get my third and final “Arlington 2020” article written and posted before 2021 rolls in. I’ve written these articles to paint a picture of Arlington’s housing stock, and how our housing costs have changed over time. The first article looked at the number of one-, two-, and three-family homes and condominiums in Arlington. The second article looked at how the costs of these homes has varied over time.

In this article, I’m going to look at the per-unit costs for our different housing types. The per-unit cost is just the assessed value, divided by the number of units. For condos and single-family homes, the unit cost is simply the assessed value. For two-family homes, it’s the assessed value divided by two. For a ten-unit apartment building, it’s the assessed value divided by ten. We’ll look at the price ranges within housing types, as well as the general differences between them.

The information here doesn’t include residential units from Arlington’s 76 mixed-use buildings. (My copy of the assessor’s data doesn’t distinguish between residential and commercial units in these buildings; I’ll try to say more about them in 2021.) It also omits units owned by the Arlington Housing Authority.

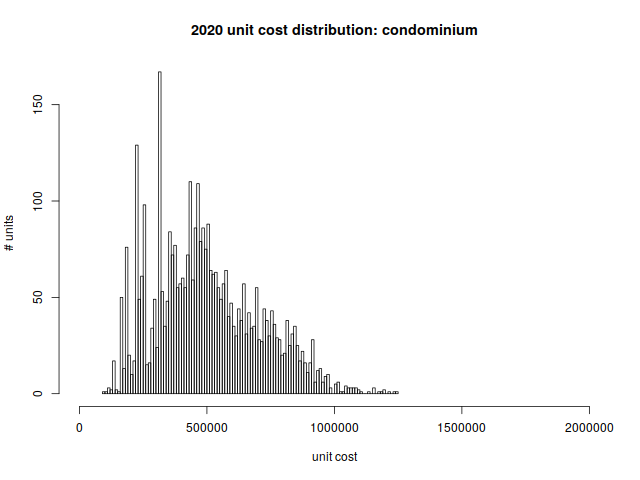

Condominiums

Condominiums provide the most variety and cost diversity. A condo can be half of a duplex, or part of a much larger multi-family building. The low end of the scale tends to be 500–600 square foot units that were built in the 1960’s; the high end tends to be more spacious new construction.

This graph is a histogram, as are the others in this article. The horizontal axis shows cost per unit, and the vertical axis shows the number of units in each particular cost band.

The per-unit price distribution is

| min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $92,600 | $344,450 | $473,100 | $500,086 | $640,850 | $1,241,000 |

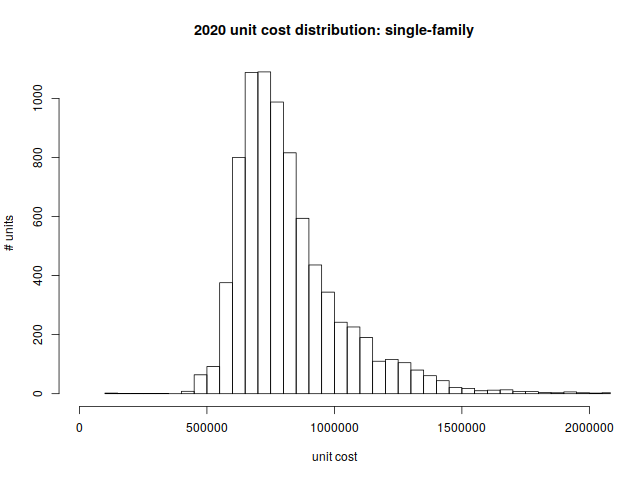

Single-family homes

Single family homes are heavily concentrated around the $700,000 mark. There’s very little available for less than a half million dollars.

Per unit rice distribution:

| min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $103,700 | $679,900 | $771,900 | $825,172 | $908,750 | $3,232,700 |

The $103,700 single-family home deserves some explanation. The property straddles the border between Arlington and Lexington; it appears that the $103k assessed value reflects the portion that lies in Arlington.

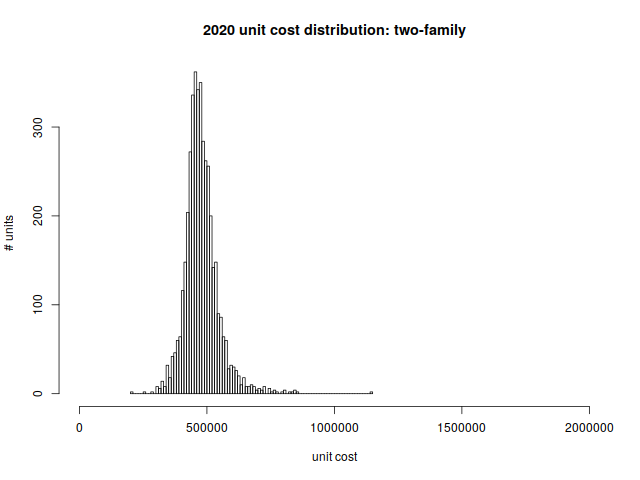

Two-family Homes

Two-family homes are the bread and butter of East Arlington; they’re also common in the blocks off Mass ave near Brattle Square and the heights. Many of these homes are older and non-conforming, and they’re gradually being renovated and turned into condominiums.

As a reminder, these are costs per unit (as opposed to the cost of the entire two-family home).

Per unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $209,050 | $440,550 | $472,000 | $479,175 | $508,588 | $1,140,450 |

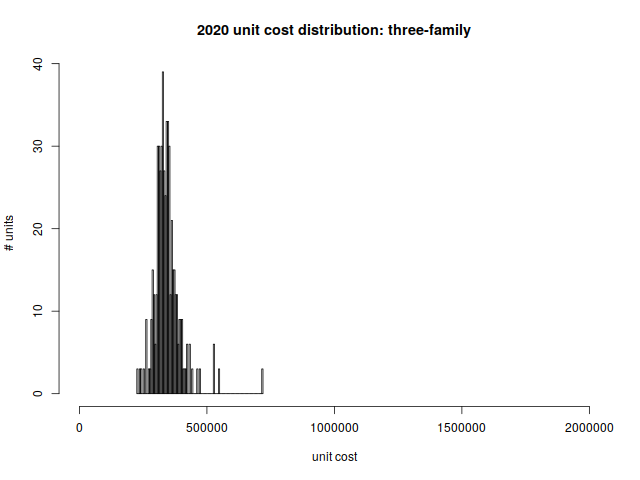

Three-family Homes

Unlike Dorchester and Somerville, three-family homes are not a staple of Arlington’s housing stock. But we have a few of them. Most were built between 1906 and 1930.

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $227,567 | $313,733 | $336,950 | $344,292 | $362,600 | $719,000 |

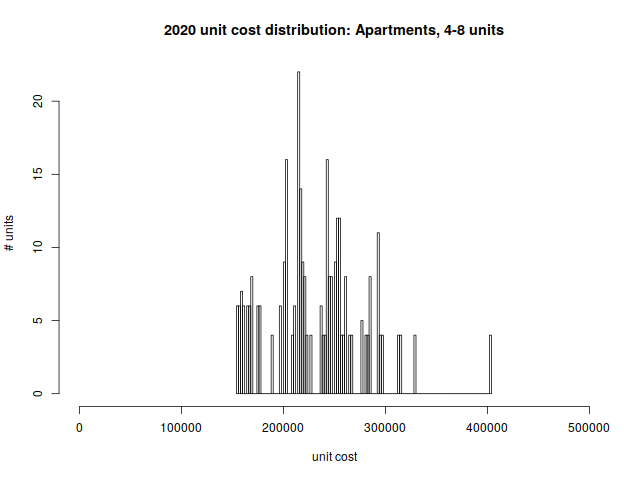

Small Apartments (4–8 units)

The majority of Arlington’s small apartment buildings were constructed during the first half of the 20th century. The most recent one dates from 1976.

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $154,950 | $202,950 | $227,775 | $231,619 | $255,775 | $403,875 |

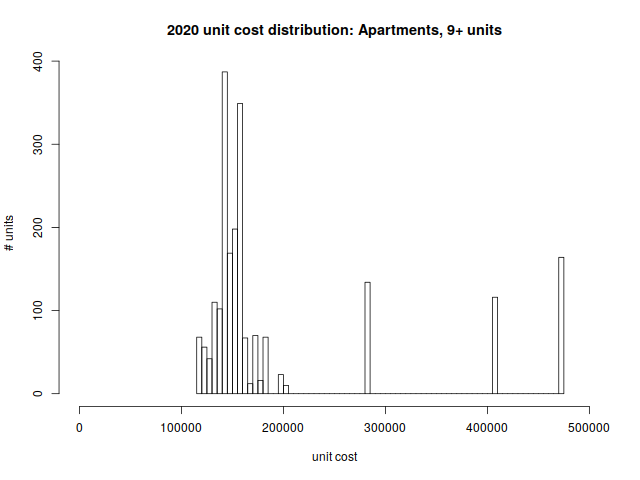

Large Apartments (9+ units)

You’ll see three outliers in the per unit-cost distribution for large apartment buildings. These correspond to the newest apartment complexes in Arlington: The Legacy (2000), Brigham Square (2012), and Arlington 360 (2013).

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $117,013 | $141,383 | $153,006 | $195,789 | $170,973 | $474,631 |

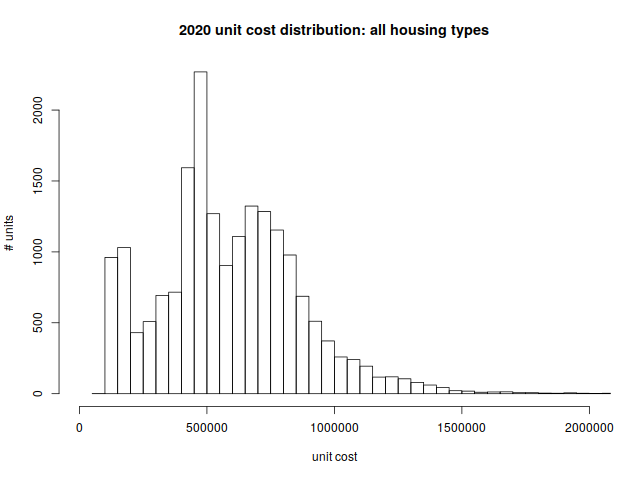

All combined

Finally, we’ll put it all together in one picture, representing nineteen-thousand and some odd homes in town.

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $92,600 | $417,175 | $555,825 | $587,975 | $759,900 | $3,232,700 |

While there are lower-priced options available, a person coming to Arlington should expect to buy (or rent) a property that costs just shy of half a million dollars (or more).

Here is a spreadsheet with the cost distributions mentioned in this article.

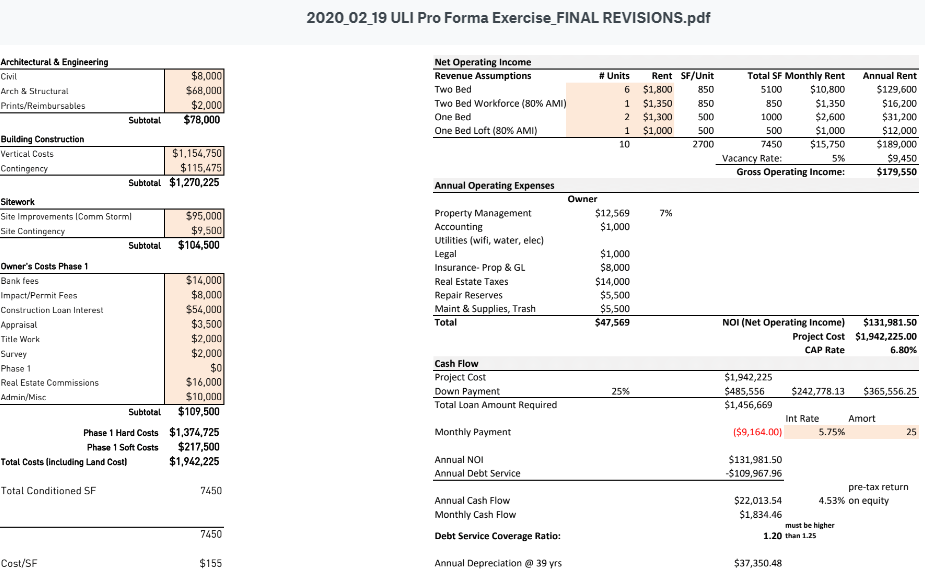

Dave Weinstock, an Arlington resident interested in affordable housing wondered about the concept of “developer math”. The math involved in planning an affordable housing projects is a problem that needs to get solved in order to have anything built here in Arlington, or anywhere. This topic comes up frequently in community discussions about the need for more housing.

Questions are raised around:

- 1- Why build so many units vs. smaller buildings

- 2- Why parking is costly and inefficient use of land

- 3- Why can’t more affordable or all affordable units be built?

- 4- The cost of subsidizing affordable units and how that may translate to higher rental rates/costs, etc.

Dave found a great Architecture and Development firm in Atlanta (Kronberg Urbanists + Architects, based in Atlanta GA) that lays out a nice presentation, includes sample proformas, and real life scenarios that may help us understand this piece of the puzzle better when evaluating any project and how developers may be incented to build certain types of projects or do certain types of work.

Here is a link, reformatted to be within this website, to the presentation, showing the varieties of choices, costs, formulas and outcomes developers consider before deciding if the project can be built: https://equitable-arlington.org/developer-math_kua_071420/

Much of our hope for more affordable housing depends on the market forces of capitalism and the willingness of developers to build for good, not just for profit. But the developers must be able to cover their costs. Many communities are highly skeptical of developers, assuming the community will get tricked, the developer will get greedy and the promised housing will be a disappointment. Trust is needed. But so is verification. We all need to learn the developer math.

What are the math factors that a developer considers before deciding to build affordable housing?

Here is a link to the original presentation. https://www.kronbergua.com/post/mr-mu-let-s-talk-about-math

(Barbara Thornton, Arlington and Roberta Cameron, Medford)

Our communities need more housing that families and individuals can afford. From 2010 to 2017, Greater Boston communities added 245,000 new jobs but only permitted 71,600 new units of housing. Prices are escalating as homebuyers and renters bid up the prices of the limited supply of housing. As a result, one quarter of all renters in Massachusetts now spend more than 50% of their income on housing. (It should be only about 30% of monthly gross income spent on housing costs.) Municipalities have been over-restricting housing development relative to need. The expensive cost of housing not only affects individual households, but also negatively affects neighborhoods and the region as a whole. Lack of affordability limits income diversity in communities. It makes it harder for businesses to recruit employees.

Over the last two years, researcher Amy Dain, commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, has systematically reviewed the bylaws, ordinances, and plans for the 100 cities and towns around Boston to uncover how local zoning affects multifamily housing and why local communities failing to provide enough additional housing to keep the prices from skyrocketing for renters and those who want to purchase homes.

Interested in housing affordability and why the cost of housing is increasing so dramatically to prevent average income residents from affording homes in the 100 municipalities around Boston? Arlington and Medford residents are pleased to welcome author Amy Dain to present her report, THE STATE OF ZONING FOR MULTIFAMILY HOUSING IN GREATER BOSTON (June 2019). Learn more about the so-called “paper wall” restricting production, common trends in local zoning, and best practices to increase production going forward. Learn about efforts in Medford and Arlington to increase housing production and affordable housing and how you can get involved. Thursday, July 25, 2019, 7:00 PM at the Medford Housing Authority, Saltonstall Building, 121 Riverside Avenue, Medford. (Parking is available.)

To access the full report, go to: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

The Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, which commissioned the study, provides the following summary of the four principal findings and takeaways:

1) Very little land is zoned for multi-family housing.

For the most part, local zoning keeps new multi-family housing out of existing residential neighborhoods, which cover the majority of the region’s land area.

In addition, cities and towns highly restrict the density of land that is zoned for multi-family use via height limitations, setbacks, and dwelling units per acre. Many of the multi-family zones have already been built out to allowable densities, which mean that although multi-family housing is on the books, it does not exist in practice.

At least a third of the municipalities have virtually no multi-family zoning or plan for growth.

Takeaway: We need to allow concentrated density in multi-family zoning districts that are in sensible locations and allow for incremental growth over a larger area.

2) We are moving to a system of project-by-project decision-making.

Unlike much of the rest of the country, Massachusetts does not require communities to update their zoning on a regular basis and make it consistent with local plans. Although state law ostensibly requires municipalities to update their master plans every ten years, the state does not enforce this provision and most communities lack up-to-date plans.

Instead, the research documents a trend away from predictable zoning districts and toward “floating districts,” project-by-project decision-making, and discretionary permits. Dain found that 57% of multi-family units approved in the region from 2015-2017 were approved by special permit, 22% by 40B (including “friendly” 40B projects), 7% by use variance, and only 14% by “as-of-right” zoning.

There also seems to be a trend toward politicizing development decisions by shifting special permit granting authority to City Council and town meeting. The system emphasizes ad hoc negotiation, which in some cases can achieve a more beneficial project. Yet the overall outcome is a slower, more expensive development process that produces fewer units. Approving projects one by one inhibits the critical infrastructure planning and investments needed to support the growth of an entire district.

Takeaway: We would be better served by a system that retains the benefits of flexibility while offering more speed and predictability.

3) The most widespread trend in zoning for multi-family housing has been to adopt mixed-use zoning.

83 of out of 100 municipalities have adopted some form of mixed-use zoning, most in the last two decades. There is a growing understanding that many people, both old and young, prefer to live in vibrant downtowns, town centers and villages, where they can easily walk to some of the amenities that they want. Malls, plazas and retail areas are increasingly incorporating housing and becoming lifestyle centers.

Yet with few exceptions, the approach to allowing housing in these areas has been cautious and incremental. These projects are only meeting a small portion of the region’s need for housing and often take many years of planning to realize. In addition, the challenges facing the retail sector can make a successful mixed-use strategy problematic. Commercial development tends to meet less opposition than residential development, even in mixed-use areas.

Takeaway: We need more multi-family housing in and around mixed-use hubs, but not require every project to be mixed-use itself.

4) Despite their efforts, communities continue to build much more new housing on their outskirts rather than in their town centers and downtowns.

About half of the communities in the study permitted some infill housing units in their historic centers, but her case studies show that these infill projects are modest in scale and can take up to 15 years to plan and permit.

On the other hand, many more units are getting built in less-developed areas with fewer abutters. This includes conversion of former industrial properties, office parks, and other parcels disconnected from the rest of the community by highways, train tracks, waterways or other barriers. This much-needed housing can be isolated even when dense, and still car-dependent because of limited access to public transportation and lack of walkability.

Takeaway: We need to allow more housing in historic centers as well as incremental growth around those centers. Furthermore, we need to plan an integrated approach to growth districts so that they can be better connected to the community and the region.