The citizen participation process including presentations, discussions, public hearings, letters and comments has been long and arduous. The issues are complicated and sometimes feelings run high. In such situations, there can be a feeling that citizens have not been heard. This document, “Guide to Zoning Amendments Related to Multifamily Uses and Mixed-Use“, summarizes many of the issues that have been raised and the changes that have been made in the zoning Articles as a result of the citizen participation in the public review process. Citizens have been heard.

Related articles

As the public hearings on the zoning articles proceeded in late winter and early spring, 2019, it became clear that there was a very strong sentiment that the proposed increase in density in these designated zoning districts should result in an increase in affordable housing in Arlington. This coincided with the approved 2015 Master Plan’s stated goals:

- Encourage mixed-use development that includes affordable housing, primarily in well-established commercial areas.

- Provide a variety of housing options for a range of incomes, ages, family sizes, and needs.

- Preserve the “streetcar suburb” character of Arlington’s residential neighborhoods.

- Encourage sustainable construction and renovation of new and existing structures (see ch. 5, pg 77++ for housing section)

- The Yes on 16 report supports the citizen initiated petition resulting in Article 16 and demonstrates the tremendous impact of rapidly increasing land values on the overall affordability of property in Arlington. Building a stack of homes on one footprint is far more financially affordable than creating a single home on the same footprint of land.

In the past few weeks, a number of highly respected Arlington organizations have come out in support of the MBTA Communities Plan. Here are a few. We will continue to update this list as it grows.

Greater Boston Interfaith Organization

This week the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization’s Arlington members released a letter of support, stating:

Arlington GBIO members support the Arlington Redevelopment Board’s proposal for the Article 12 of the Fall 2023 Special Town Meeting (MBTA Communities Overlay District) to enact changes in Arlington’s zoning by-laws that will allow for more multi-family housing to be built by right. We support an article that goes beyond the minimum capacity required by law in order to encourage the construction of a meaningful number of additional homes of various sizes beyond the number already present in Arlington.

Arlington Chamber of Commerce

The Arlington Chamber of Commerce sent a letter supporting the MBTA Communities Plan on October 2, saying:

The Arlington Chamber of Commerce believes that the MBTA Working Group’s proposal presents a strong plan for both housing and commercial growth. Arlington’s existing and future small businesses will benefit from an increased customer base and foot traffic resulting from additional housing units.

Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

Arlington’s Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion wrote to the Arlington Redevelopment Board in support of the MBTA Communities Plan:

The DEI Division would like to formally voice our support for the Working Group’s effort to create a zoning plan that would allow for more multi-housing opportunities at varied price points across Arlington. Only 9% of Arlington’s land is devoted to multifamily housing, and even where building multi-family housing is allowable, it is not permitted by right. This does not provide suitable conditions for a range of housing types to exist. The current price point of homes in Arlington are far beyond the reach of most residents, regardless of their status as a member of a protected class. stating:

Read the full letter. [PDF]

Clean Energy Future Committee

The Clean Energy Future Committee said passage of the MBTA Communities Zoning was crucial because:

Passage of the MBTA Communities zoning amendment at this fall’s Special Town Meeting is the only viable pathway for Arlington to participate in the State’s Fossil Fuel Free Demonstration Program (Demonstration Program), which would allow implementation of the Clean Heat bylaw and home rule petition passed overwhelmingly by Arlington Town Meeting in 2020. Participation in the Demonstration Program will allow the Town to prohibit the installation of natural gas, oil, propane, and other fossil fuel infrastructure in new buildings and major renovations. Town Meeting sent a clear message in 2020 that enacting the Fossil Fuel Bylaw was a priority, and we–the CEFC, Town administrators, and elected and appointed bodies–have an obligation to act upon that priority; passage of the MBTA Communities zoning amendment is an essential step to carrying out the will of Town Meeting.

Mothers Out Front

As we previously reported, the Arlington chapter of Mothers Out Front supports the MBTA Communities Plan, writing:

A revised zoning by-law to allow for more multi-family housing will reduce pressure to build single family homes on undeveloped land elsewhere in Massachusetts. This safeguards undisturbed ecosystems and provides real alternatives to automotive commutes in the region, reducing both congestion and fossil fuel emissions.

It’s the time of year when folks in Arlington are taking out nomination papers, gathering signatures, and strategizing on how to campaign for the town election on Saturday April 1st. The town election is where we choose members of Arlington’s governing institutions, including the Select Board (Arlington’s executive branch), the School Committee, and — most relevantly for this post — Town Meeting.

If you’re new to New England, Town Meeting is an institution you may not have heard of, but it’s basically the town’s Legislative Branch. Town Meeting consists of 12 members from each of 21 Precincts, for 252 members total. Members serve three-year terms, with one-third of the seats up for election in any year, so that each precinct elects four representatives per year (perhaps with an extra seat or two, as needed to fill vacancies). For a deeper dive, Envision Arlington’s ABC’s of Arlington Government gives a great overview of Arlington’s government structure.

As our legislative branch, town meeting’s powers and responsibilities include:

- Passing the Town’s Operating Budget, which details planned expenses for the next year.

- Approving the town’s Capital Budget, which includes vehicle and equipment purchases, playgrounds, and town facilities.

- Bylaw changes. Town meeting is the only body that can amend the towns bylaws, including ones that affect housing — what kinds can be built, how much, and where.

Town Meeting is an excellent opportunity to serve your community, and to learn about how Arlington and its municipal government works. Any registered voter is eligible to run. If this sounds like an interesting prospect, we encourage you to run! Here’s what you’ll need to do:

- Have a look at the town’s Information for new and Prospective Town Meeting Members.

- Contact the Town Clerk’s office to get a set of nomination papers. You’ll need to do this by 5:00 PM February 12th, 2025 at the latest.

- Gather signatures. You’ll need signatures from at least ten registered voters in your precinct to get on the ballot (it’s always good to get a few extra signatures, to be safe).

- Return your signed nomination papers to the Clerk’s office by February 14, 2025 at 5:00 PM.

- Campaign! Get a map and voter list for your precinct, knock on doors, and introduce yourself. (Having a flier to distribute is also helpful.)

- Vote on Saturday April 5th, and wait for the results.

Town Meeting traditionally meets every Monday and Wednesday at 8:00 PM, starting on the 4th Monday in April (which is April 28th this year), and lasting until the year’s business is concluded (typically a few weeks).

If you’d like to connect with an experienced Town Meeting Member about the logistics of campaigning, or the reality of serving at Town Meeting, please email info(AT)equitable-arlington.org and we’d be happy to make an introduction.

During the past few years, Town Meeting was our pathway to legalizing accessory dwelling units, reducing minimum parking requirements, loosening restrictions on mixed-use development in Arlington’s business districts, and adopting multi-family zoning for MBTA Communities. Aside from being a rewarding experience, it’s a way to make a difference!

This timely report on the question of affordable housing vs. density comes from the California Dept. of Housing & Community Development and mirrors the situation in the region surrounding Arlington MA.

Housing production has not kept up with job and household growth. The location and type of new housing does not meet the needs of many new house- holds. As a result, only one in five households can afford a typical home, overcrowding doubled in the 1990’s, and too many households pay more than they can afford for their housing.

Myth #1

High-density housing is affordable housing; affordable

housing is high-density housing.

Fact #1

Not all high density housing is affordable to low-income families.

Myth #2

High-density and affordable housing will cause too much traffic.

Fact #2

People who live in affordable housing own fewer cars and

drive less.

Myth #3

High-density development strains public services and

infrastructure.

Fact #3

Compact development offers greater efficiency in use of

public services and infrastructure.

Myth #4

People who live in high-density and affordable housing

won’t fit into my neighborhood.

Fact #4

People who need affordable housing already live and work

in your community.

Myth #5

Affordable housing reduces property values.

Fact #5

No study in California has ever shown that affordable

housing developments reduce property values.

Myth #6

Residents of affordable housing move too often to be stable

community members.

Fact #6

When rents are guaranteed to remain stable, tenants

move less often.

Myth #7

High-density and affordable housing undermine community

character.

Fact #7

New affordable and high-density housing can always be

designed to fit into existing communities.

Myth #8

High-density and affordable housing increase crime.

Fact #8

The design and use of public spaces has a far more

significant affect on crime than density or income levels.

See an example of a “case study” of two affordable housing developments in Irvine CA, San Marcos at 64 units per acre.

San Paulo at 25 units per acre.

Both are designed to blend with nearby homes.

State Senator Cindy F. Friedman has written a letter to Town Meeting Members supporting Warrant Article 12 and a meaningful MBTA Communities Plan. She writes:

We all want Arlington and Massachusetts to remain welcoming, accessible places to live. In addition to our deficit of housing, I recognize the importance of encouraging smaller, more sustainable housing in walkable areas. Arlington’s Warrant Article 12 will provide a meaningful framework for making progress in these areas. The problems we are experiencing now —out of reach housing prices for new construction and existing homes — exacerbate the crisis and are seriously threatening the economic vibrancy of our communities.

To read Friedman’s full letter, click here for the PDF.

The City of Somerville estimates that a 2% real estate transfer fee — with 1% paid by sellers and 1% paid by buyers, and that exempts owner-occupants (defined as persons residing in the property for at least two years) — could generate up to $6 million per year for affordable housing. The hotter the market, and the greater the number of property transactions, the more such a fee would generate.

Other municipalities are also looking at this legislation but need “home rule” permission, one municipality at a time, from the state to enact it locally. Or, alternatively, legislation could be passed at the state level to allow all municipalities to opt into such a program and design their own terms. This would be much like the well regarded Community Preservation Act (CPA) program that provides funds for local governments to do historic preservation, conservation, etc.

This memorandum from the City of Somerville to the legislature provides a great deal of information on the history, background and justification for such legislation.

House bill 1769, filed January, 2019, is an “Act supporting affordable housing with a local option for a fee to be applied to certain real estate transactions“.

COMMENT:

KK: This article suggests Arlington may be likely to pass a real estate transfer tax: https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/12/19/boston-one-step-closer-to-a-luxury-real-estate-transfer-tax/

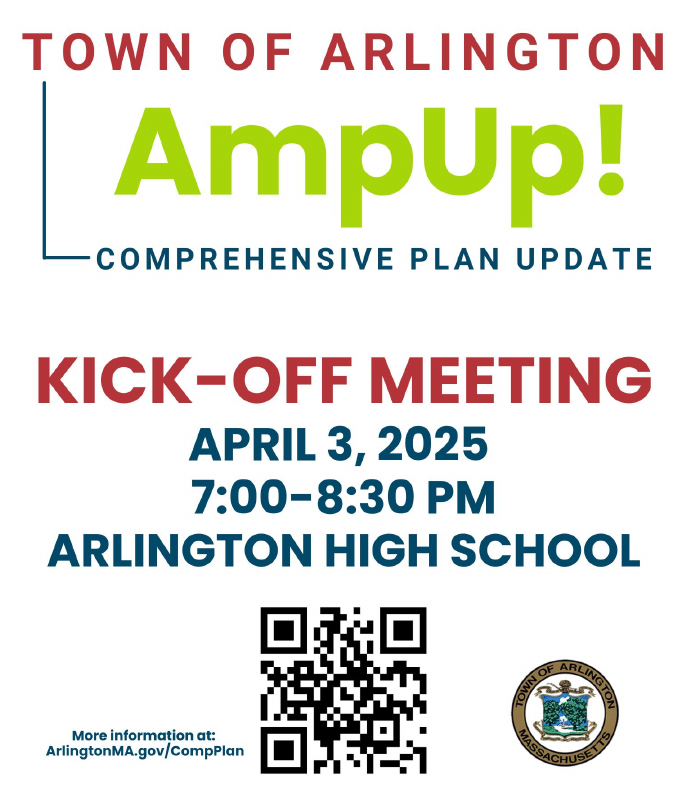

The kick-off event for updating Arlington’s Comprehensive Plan (formerly called the Master Plan) is just around the corner on April 3rd from 7-8:30 PM in the Arlington High School Cafeteria!

A Comprehensive Plan is a long-range plan for the Town, and an opportunity for the community to come together and imagine what Arlington could look like in ten or fifteen years. It covers things like housing, business development, parks and open spaces, town services and facilities, and transportation. The kickoff meeting is the first step in building that vision.

Arlington residents of all ages are invited to attend this event, where you can expect a presentation followed by small group discussions. The effort will continue throughout the year, and it’s important to hear from as many residents as possible. Please join if you can!

For more information and to add the meeting to your calendar, see ArlingtonMA.gov/CompPlan.

Text of Warrant Article 8: (To be considered at Special Town Meeting (Virtual), Mon. 11/16/20 at 8:00 p.m.)

“ARTICLE 8 ACCEPTANCE OF LEGISLATION/BYLAW AMENDMENT/ MUNICIPAL AFFORDABLE HOUSING TRUST FUND

To see if the Town will vote to accept Massachusetts General Laws c. 44 § 55C, to authorize the creation of a Municipal Affordable Housing Trust Fund to support the development of affordable housing in Arlington, establish a new bylaw for the administration of same; or take any action related thereto. (Inserted by the Select Board)”

What will it do? How will it work?

A Proactive Step to Address Housing Affordability. With a municipal affordable housing trust, Arlington will join more than 113 Massachusetts municipalities that have formed a housing trust fund to support a proactive strategy for building housing affordability. The Trust is a small step the Town can take to more proactively address the housing affordability crisis that challenges many of our current residents and makes Arlington increasingly inaccessible to new residents. Creating affordable housing can also be a strategy for maintaining or increasing diversity.

Ability to Act Quickly.

A primary benefit of a housing trust is to enable the Town to act quickly to support or participate in transactions that increase or preserve affordable housing in Arlington. Without a Trust, the Town does not have the flexibility or agility to act quickly. Following are some examples, though there are many other ways that trusts can and do advance housing affordability:

• Financing the acquisition and/or development of market properties for conversion to affordable housing by a nonprofit developer;

• Purchasing an existing affordable home to ensure resale to another low income buyer, or purchasing a market rate home to create an affordable homeownership opportunity;

• Providing flexible financing to increase the number of affordable units or reduce income levels in existing or new projects that include affordable housing.

Developing a Housing Trust Strategy Over Time.

The strategies to be pursued by the Trust would be set forth by the Trustees in a plan or proposal(s) they would lay out after they are appointed, most likely after/through a process of public engagement. The specific strategies are, deliberately, not part of the warrant article or the Bylaw proposed for adoption. This allows the Town the flexibility to set and modify the Town’s housing strategies over time, in a manner that is responsive to the public and its elected representatives. The Bylaw requires the strategy or plan, and most major Trust decisions, to be approved by the Select Board, and Town investments in the Trust would still require Town Meeting approval.

Funding the Affordable Housing Trust Fund.

Creating affordable housing requires substantial subsidy. The Trust’s ability to cause more affordable housing to be created or preserved in Arlington will be directly related to the availability of resources to fund it and leverage additional state and federal resources. The vote before the Special Town Meeting this fall will not provide any funding for the Trust.

While it is anticipated that the Trust might receive initial funding via a grant of Community Preservation Act funds from the CPA Committee, to increase our impact, more resources will be needed.

How Other Communities Fund Their Housing Trust Funds.

The Community Preservation Act is the most common source of funding, but the most impactful trusts tend to have a variety of funding sources that result in a steady flow of financial resources into the Trust. Other municipalities have tapped into a variety of additional sources, including inclusionary zoning payments, federal HOME funds, voluntary/negotiated developer payments, proceeds from sale of tax foreclosed or other Town-owned properties, cell tower payments, cannabis-related revenue, short-term rental fees, fees for managing housing lotteries, sale of bonds, general municipal funding, and private donations. Many also donate excess town property to their housing trust for sale and redevelopment as affordable or mixed income housing. More recently, a number of cities and towns have proposed home rule petitions that would allow them to impose a small fee on the transfer of real property to fund their housing trusts, and there is state legislation proposed to authorize cities and towns to impose such transfer fees without sending a Home Rule Petition to the state legislature.

Building Trust Resources Through a Transfer Fee.

The Housing Plan Implementation Committee originally recommended that Town Meeting adopt a bylaw creating a housing trust and create a funding source for it by voting to authorize the filing of a home rule petition to impose a modest real estate transfer fee. Although the Select Board elected to defer consideration of the transfer fee until 2021, such a fee is attractive to many, because it would be borne only by those selling their Arlington homes or properties, and because it provides a mechanism to capture a very small portion of the extraordinary equity increase that Arlington property owners have realized over many years due to regional market forces. The details of such a fee are important and merit further discussion, but it presents a promising potential revenue source to empower the Trust to be proactive.

The Process.

The article in front of the Special Town Meeting would start the process of creating a municipal affordable housing trust. Once approved by Town Meeting the Affordable Housing Trust Bylaw would be submitted to the Attorney General to certify its consistency with the state law governing housing trusts within 90 days. Once so certified, the Town Manager will appoint trustees, including at least one member of the Select Board. Once these appointments are confirmed by the Select Board, the Trustees themselves would lead the process of proposing an initial set of goals and strategies for the Trust to implement, after approval by the Select Board.

Financial Stability & Accountability.

The Trust will be governed by the MAHT law passed in 2005 that specifies powers and limitations for trusts of this type. The proposed Bylaw has been reviewed and modified pursuant to suggestions of the Finance Committee to ensure accountability and financial stability. The Trust will be managed by the Treasurer, will be audited annually, will have legal and practical limitations on its borrowing capacity, and will not have the power to pledge the full faith and credit of the Town.

To learn more about municipal affordable housing trusts, refer to the MHP Municipal Affordable Housing Trust Fund Guide, v.3

******

This information was prepared by Karen Kelleher, Arlington Town Meeting Member, Precinct 5, Member, Arlington Housing Planning Implementation Committee and Executive Director, LISC Boston ( Local Initiative Support Corporation)