A new report for Boston Indicators, “Exclusionary by Design”, shows the clear intent of many Greater Boston suburbs to resist racial and class integration in the 1970s. Housing scholar Amy Dain demonstrates how racial prejudice and class exclusion figured into suburbs’ downzoning in the 1970s; and how putatively legitimate concerns like tax revenue, aesthetic continuity, and the environment served the cause of exclusion.

Read the “Exclusionary by Design” report, and see the accompanying 1-hour webinar with Amy Dain, Luc Shuster of Boston Indicators and Ted Landsmark of Northeastern University.

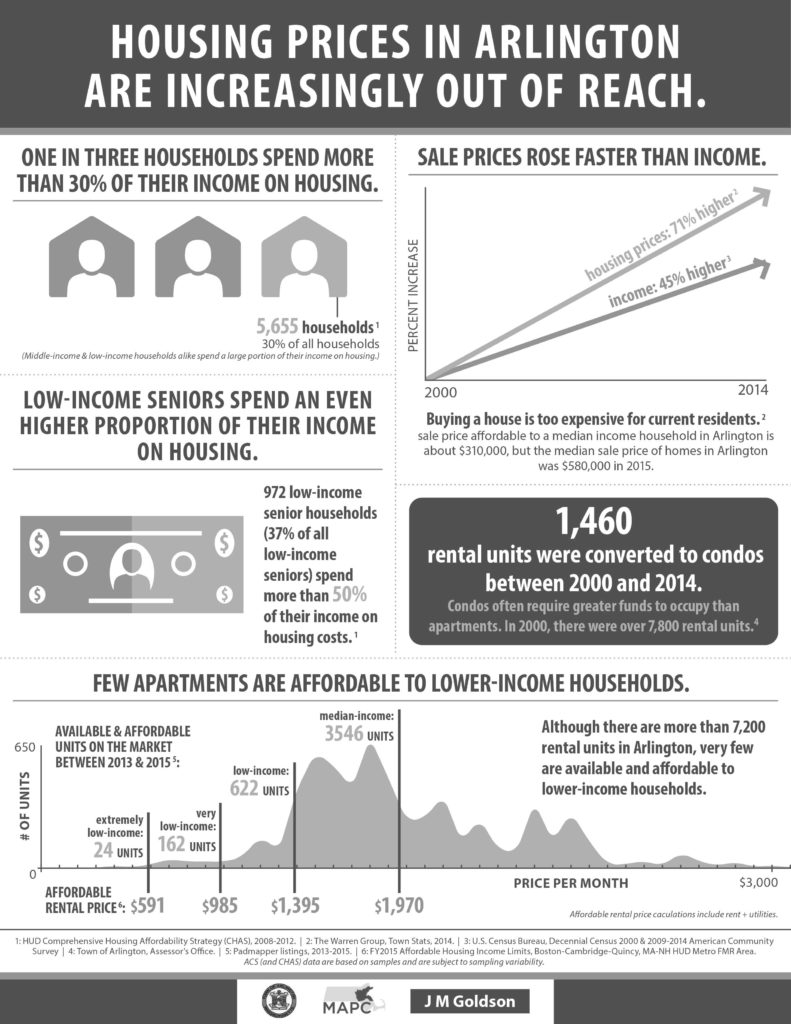

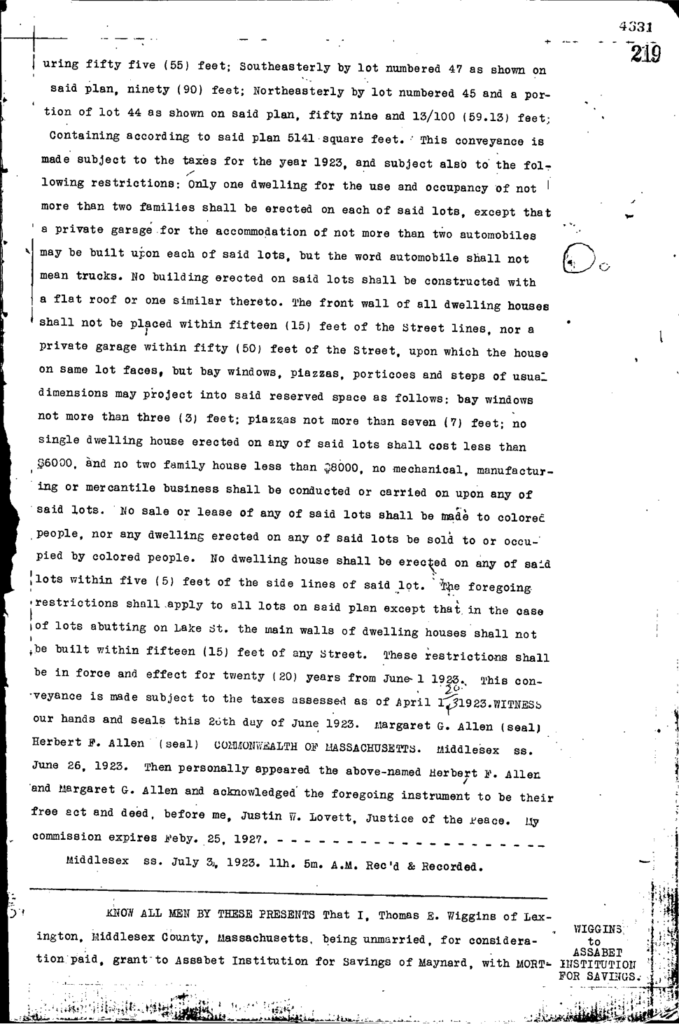

“This research finds widespread evidence that over the past 100 years, zoning has been used by cities and towns across Greater Boston as a tool for excluding certain groups of people, including:

- Racial minorities, especially Black residents

- Lower-income and working-class residents

- Families with school-aged children• Religious minorities

- Immigrants

- And, in some cases, any newcomers/outsiders at all”

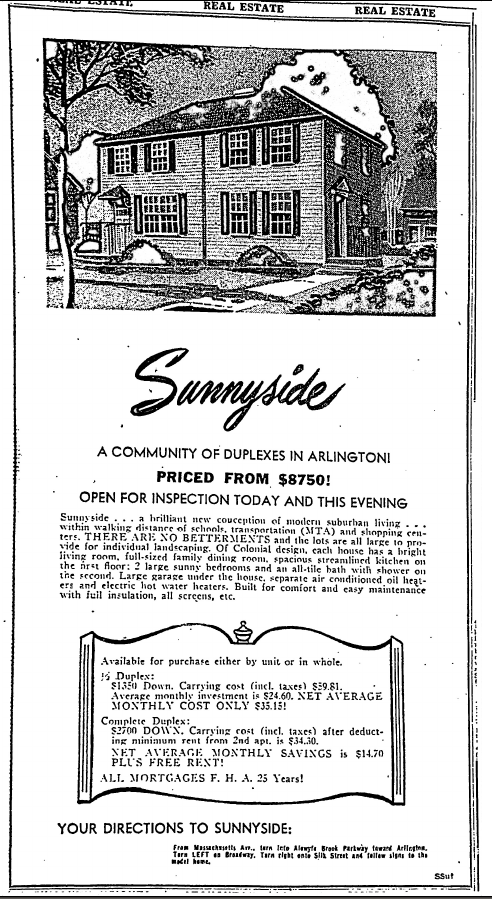

Low Diversity is No Accident

In the 1970s, municipalities were ordered by state law to create Growth Policy Statements – but with no mandate that communities actually endorse growth nor inclusion. Exclusionary language in these statements was seemingly anodyne, seeking to preserve the “present characteristics of their communities” or “socio-economic status“. In several cases the fear of integration was quite apparent: Milton’s statement referred to problems in “surrounding communities” (ie Mattapan and Dorchester) and “breakdown of society”; both Milton and Melrose make mention of the pressures caused by people “moving out of Boston”. Belmont’s plan explicitly calls for the town to stay “relatively expensive … [so as to] attract only those families so economically situated.”

The intent of such language was not somehow lost on people in that era. Needham’s Local Growth Policy Statement included, but pointedly disavowed its own “Appendix A” — a dissenting statement by the Congregational Church of Needham, calling out the town’s exclusionary aims and endorsing a vision of inclusive growth.

In addition, in many places where multi-family housing was theoretically allowed, “poison pill” requirements and impediments were added to make such building a practical impossibility. More recently we have seen the ironic use of infeasible “inclusionary zoning” requirements – which ensure that no affordable housing can actually be built.

The same language, un-evolved and unrefined, is still invoked by “neighborhood defenders” today. Our current housing affordability crisis and segregation is the plain result. The report is a sobering, enlightening read – essential for any active citizen or town official in eastern Massachusetts.