The presentation, dated March 11, 2019, includes slides used to present the information necessary to understand the rationale for zoning changes, the location of the zoning areas under consideration and the charts, tables and maps that help describe the situation. The proposed zoning changes, especially articles 6, 7, 8, 11 and 16, only cover changes affecting about 7% of the Town, those parts of the Town that are currently zoned R4-R7 and the B zoning districts.

Related articles

State Representatives Dave Rogers (Arlington, Belmont and Cambridge) and Sean Garballey (Arlington, Medford) have sent a letter to Town Meeting Members backing the MBTA Communities Plan. They write:

We believe the plan in front of Town Meeting provides a meaningful framework to address the housing shortage in Arlington.

To read the full letter, click here for PDF.

The calculation for what is permanently affordable housing is complicated. Arlington’s affordable rate is based on a region that includes the Area Median Income (AMI) of the Cambridge-Boston-Quincy region. The rate is adjusted and reset periodically according to federal HUD guidelines. The rate is applied based on family size and on the Town’s definition of what income level is eligible for Inclusionary Housing opportunities in Arlington. In Arlington a 3 person family would qualify if their income was under 60% of AMI. At this time, that is approximately $58,000 for a family of three.

For more information, see this table of income limits from Cambridge’s Community Development Department, and this short paper on affordable housing from the City of Boston.

Article 16 is a proposal to encourage the production of affordable housing in the town of Arlington. I brought this article to town meeting for several reasons, namely, our increasing cost of housing and our increasing cost of land. Arlington is part of the Metropolitan Boston area; we share borders with Cambridge, Somerville, and Medford, and are a mere 5.5 miles from Boston itself. Years ago, people moved out of cities and into the suburbs. That trend has reversed during the last decade, and people are moving back to urban areas, including Metro-Boston. Metro-Boston is a good source of jobs; people come here to work and want to live nearby. That obviously puts pressure on housing prices, and Arlington is not immune from that pressure.

Another reason for proposing Article 16 was my desire to start a conversation about the role our zoning laws play in the cost of housing, and how they might be used to relieve some of that burden. During the 20th century people discovered that one cannot draw a line on a map and say “upper-class households on this side, lower-class households on that side”, but one can draw a line on a map and say “single-family homes on this side, and apartments on that side”. For all practical purposes, the latter achieves the same result as the former. When zoning places a threshold on the cost of housing, it determines who can and cannot afford to live in a given area.

Today 70% of Arlington’s land is exclusively zoned for single family homes, the predominant form of housing in town. In 2013, the median cost of a single-family home was $472,850; this rose to $618,800 in 2018 — an increase of 31%. We can break this down further. The median building cost for a single-family building rose from $226,300 in 2013 to $248,100 in 2018 (an increase of 9.6%), and the median cost for a single-family lot rose from $243,700 to $360,900 (an increase of 48%). Land is a large component of our housing costs, and it continues to rise. Certain neighborhoods (e.g., Kelwyn Manor) saw substantial increases in land assessments in 2019, enough that the Assessor’s office issued a statement to explain the property tax increases. To that end, multifamily housing is a straightforward way to reduce the land costs associated with housing. Putting two units on a lot instead of one decreases the land cost by 50% for each unit.

Article 16 tries to encourage the production of affordable housing (restricted to 60% of the area median income for rentable units and 70% for owner-occupied units). It works as follows:

- Projects of six or more units must make 15% of those units affordable. This is part of our existing bylaws.

- Projects of twenty or more units must make 20% of those units affordable. This is a new provision in Article 16.

- Projects of six or more units that produce more than the required number of affordable units will be eligible for density bonuses, according to the proposed section 8.2.4(C). Essentially, this allows a developer to build a larger building, in exchange for creating more affordable housing.

- Projects of six or more units that produce only the required number of affordable units are not eligible for the density bonuses contained in 8.2.4(C).

- Projects of 4-5 units will be eligible for the density bonuses in section 8.2.4(C), as long as they are of a use, and in a zone contained in those tables. This provision is intended to permit smaller apartments and townhouses, filling a need for residents who don’t necessarily want (or may not be able to afford) a single-family home. This provision can help reduce land costs by allowing a four-unit townhouse in place of a duplex, for example.

Historically, Arlington has had mixed results with affordable housing production, mainly due to the limited opportunity to build projects of six units or more. It is my hope that the density bonuses allow more of these projects to be built.

In conclusion, the problem of housing affordability in Arlington comes from a variety of pressures, is several years in the making, and will likely take years to address. I see Article 16 as the first step down a long road, and I ask for your support during the 2019 Town Meeting. I’d also ask for your support on articles 6, 7, and 8 which contain minor changes to make Article 16 work properly.

For Arlington’s Nov 2020 Special Town Meeting, my colleague Ben Rudick filed the following warrant article:

ARTICLE 18: ZONING BYLAW AMENDMENT/IMPROVING RESIDENTIAL INCLUSIVENESS, SUSTAINABILITY, AND AFFORDABILITY BY ENDING SINGLE FAMILY ZONING

To see if the Town will vote to amend the Zoning Bylaw for the Town of Arlington by expanding the set of allowed residential uses in the R0 and R1 zoning districts with the goal of expanding and diversifying the housing stock by altering the district definitions for the R0 and R1 zoning districts; or take any action related thereto.

(Inserted at the request of Benjamin Rudick and ten registered voters)

The Inspiration

Our goal with Article 18 is to allow two-family homes, by right, in two districts that are exclusively zoned for single-family homes. This is similar to what city of Minneapolis and the state of Oregon did in 2019. The motivations fall into three broad categories: the history of single-family zoning as a mechanism for racial segregation, environmental concerns arising from car-oriented suburban sprawl, and the regional shortage of housing and its high cost. We’ll elaborate on these concerns in the following paragraphs, and end with a proposed main motion.

Single-family zoning as a mechanism for racial segregation. Single-family zoning began to take hold in the United States during the 1920’s, after the Supreme Court declared racially-based zoning unconstitutional in 1917. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover encouraged cities and towns to adopt single-family zoning ordinances, effectively substituting segregation based on race with segregation based on economic status. The idea was furthered by the Home Owners Loan Corporation of America’s (HOLC’s) redlining maps (created between 1935 and 1940), and the Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA’s) mortgage insurance policies from 1934–1968. The HOLC designated areas with black populations as “hazardous” and actuarially risky, and the FHA used these maps when making underwriting decisions. In short, the FHA was in the business of underwriting loans to white home buyers in white neighborhoods.

Of Arlington’s 7,998 single-family homes, 4,080 (51%) were built during 1934–1968 (per Arlington Assessor’s data). The FHA was the primary mortgage underwriter during this time, and we believe it is reasonable to expect that a substantial number of these homes were originally purchased with FHA mortgages. Put another way, most of our single-family housing was likely built according to FHA guidelines of “avoiding inharmonious mixing or races”, aka segregation. Arlington’s population was 99% white in 1970 and even higher during previous decades. We certainly met the criteria of being a white community.

We believe it’s important to recognize this history, and to have a conversation about how we might restore a balance of fairness.

Environmental concerns. When compared with their multi-family counterparts, single-family homes are less energy efficient, more land intensive, and are associated with higher carbon emissions due to ransportation. Car transportation is a useful analogy; having everyone drive in their own car is more carbon-intensive than carpooling (two-family homes), which in turn is more carbon-intensive than taking the bus (3+ unit buildings). Maps created by Berkeley’s Cool Climate Project show this in a clear way: per household carbon emissions are lower in urban areas than they are in the surrounding suburbs. (Note that authors of the Berkeley report do not advocate getting rid of suburbs, but they do state that suburbs will require different carbon reduction strategies than urban areas).

We believe it is more environmentally responsible to build additional homes on sites that are already developed, rather than (say) going out to the suburban fringes along route 495 and clearing half-acre lots. If we do not provide ample housing within Arlington and other inner-ring suburbs, new workers will likely live further out and have longer, more carbon-intensive commutes. Climate change is a crisis, and our response must involve changing how we live, and that includes ending the twentieth-century pattern of suburban sprawl.

The shortage and high cost of housing. Since 2010, the fifteen cities and towns in the Metro Mayor’s coalition have added 148,000 jobs and 110,000 new residents, but have only permitted 32,500 new homes; this has added to a housing shortage that’s been growing for decades. The imbalance between supply and demand has contributed to rising prices and a very hot market. In 2019, the median sale price for homes in Arlington was $821k. We do not expect construction to be a complete solution to Arlington’s housing costs, but we do believe it is a necessary step in meeting rising demand and counteracting rising costs.

Article 18 is most likely to influence the cost of newly-constructed homes. Newly-constructed single-family homes typically sell in the $1.2M–1.5M range while condominiums in new duplexes typically fall into the $800k–1.1M range. These duplex units are not cheap, but they offer a price point roughly four hundred thousand dollars less than new single-family homes.

We also believe our proposal directly addresses three concerns raised by last year’s multi-family proposal (aka 2019 ATM Article 16):

- Concentration. Last year’s proposal would have concentrated new housing around the town’s business corridors, and Massachusetts Avenue in particular. Article 18 will spread new housing across the majority of the town, as 60% of Arlington’s land area (and 80% of its residentially-zoned land) is currently zoned exclusively for single-family homes (figures provided by Arlingtons Department of Planning and Community Development).

- Height and Shadows. Last year’s proposal would have allowed taller buildings along the commercial corridors; there were concerns about increased height, and the shadows new buildings might cast. Article 18 makes no changes to our zoning bylaw’s dimensional regulation; homes built under this bylaw could be no larger than homes we already allow, by right.

- Displacement. Last year’s proposal drew concerns that businesses and apartment renters would be displaced by new construction. Article 18 applies to districts that are exclusively zoned for single-family homes. 95% of our single-family homes are owner-occupied, and can only be rebuilt or renovated with the owner’s consent. We believe this minimizes any risk of displacement.

Finally, we expect the board will be interested in the number of homes that might be added under this proposal, and the potential impact on the school system. We’ll attempt to address those questions here.

Arlington’s report on Demolitions and Replacement Homes states an average of 27 rebuilds or substantial renovations per year, averaged over a ten year period. For the purpose of discussion, we expect the number of new homes added under this proposed bylaw change to be somewhere between half and double that amount, or 14–54 homes/year. Arlington has 7,998 single-family homes so this is a replacement rate well under 1%/year. It will be nothing like the 500 new homes/year that Arlington was building during the 1920s.

Assessing the impact on the school system amounts (in part) to estimating the number of new school students created by the addition of 14–54 homes/year. One can conceivably see this playing out according to three scenarios. Scenario 1 is simply “by the numbers”. The Housing section of Cambridge’s Alewife District Plan estimates one new student for every 17 new homes (see pg. 145), and the economic analysis of Arlington’s industrial districts gives a net increase of one new student for every 20 new condominiums (see slide 49). Both work out to an increase of 1–3 students per year for the addition of 14–54 homes. This is substantially smaller than past enrollment growth, and something the schools should easily be able to handle.

Second, one could imagine a scenario where elementary school enrollment is in modest decline, as students who entered Arlington public schools in the middle of the last decade move on to middle and high school. Here, new elementary students would utilize existing classroom space, which was created to accommodate students that came before them. It’s a scenario where enrollment stabilizes and doesn’t increase much.

Third, one could picture a scenario where any new home is immediately filled with children. Under this assumption it’s likely that any turnover of single-family homes or suitably-sized condominiums would attract families with children. With 7,998 single-family homes, there is little to prevent another demographic turnover from causing another increase in school enrollment, even if Arlington never adds a single additional home.

In summary, the effects on school enrollment are not easy to predict and several outcomes are possible. Ultimately, this will depend on Arlington’s attractiveness to young families, and our ability to retain these families once their students graduate from school.

Our Proposal to the Arlington Redevelopment Board

We propose that the Zoning Bylaw of the Town of Arlington be amended as

follows:

- By adding the letter “Y” to the “Use Regulations for Residential Districts” table in Section 5.4.3, in the row labeled “Two family dwelling, duplex”, and under the columns labeled “R0” and “R1”;

- By adding the letters “SP” to the “Use Regulations for Residential Districts” table in Section 5.4.3, in the row labeled “Six or more units in two-family dwellings or duplex dwelling on one or more contiguous lots”, and under the columns labeled “R0” and “R1”,

| Class of Use | R0 | R1 | R2 |

| Two-family dwelling | Y | Y | Y |

| Six or more units in two-family dwellings or duplex dwelling on one or more contiguous lots | SP | SP | SP |

and, by making the following changes to the definitions of the R0 and R1 districts in Section 5.4.1(A):

R0: Large Lot Single-FamilyResidential District. The Large Lot Single-FamilyResidential District has the lowest residential density of all districts and is generally served by local streets only. The Town discourages intensive land uses, uses that would detract from the single-family residential character of these neighborhoods, and uses that would otherwise interfere with the intent of this Bylaw.

R1: Single-FamilyR1 Residential District. The predominant uses in R1 are single- and two-family dwellings and public land and buildings. The Town discourages intensive land uses, uses that would detract from the single-family residential character of these neighborhoods, and uses that would otherwise interfere with the intent of this Bylaw.

Related Materials

Our Redevelopment Board Hearing

We presented Article 18 to the redevelopment board on Oct 26th. You can watch the presentation below.

The Redevelopment Board did their deliberations and voting two days later, on October 28th. Their report is available from the Town website.

At least three members of the board were supportive of the effort, but they ultimately voted to recommend this action. I attribute the no action vote to two factors. First, in January 2020 the Redevelopment board agreed to perform a public engagement campaign, to educate residents on housing issues facing the town, and to gather input on how those issues could be addressed. The public engagement effort hasn’t started yet (mainly due to the pandemic), and the board was hesitant to recommend favorable action without doing an outreach campaign first.

Second, the board was interested in attaching standards to single- to two-family conversions, and didn’t feel there was enough time in this town meeting cycle to devise an appropriate set of standards. They were interested in design requirements and collecting payments to an affordable housing trust fund. Standards are interesting idea, and worthy of further consideration. For my own taste, I’d be more inclined to ask for performance standards that tied in to Arlington’s Net Zero Action plan.

So, we are going to take the ARB’s feedback, work on the idea some more, and resubmit during a future town meeting.

(Barbara Thornton, Arlington and Roberta Cameron, Medford)

Our communities need more housing that families and individuals can afford. From 2010 to 2017, Greater Boston communities added 245,000 new jobs but only permitted 71,600 new units of housing. Prices are escalating as homebuyers and renters bid up the prices of the limited supply of housing. As a result, one quarter of all renters in Massachusetts now spend more than 50% of their income on housing. (It should be only about 30% of monthly gross income spent on housing costs.) Municipalities have been over-restricting housing development relative to need. The expensive cost of housing not only affects individual households, but also negatively affects neighborhoods and the region as a whole. Lack of affordability limits income diversity in communities. It makes it harder for businesses to recruit employees.

Over the last two years, researcher Amy Dain, commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, has systematically reviewed the bylaws, ordinances, and plans for the 100 cities and towns around Boston to uncover how local zoning affects multifamily housing and why local communities failing to provide enough additional housing to keep the prices from skyrocketing for renters and those who want to purchase homes.

Interested in housing affordability and why the cost of housing is increasing so dramatically to prevent average income residents from affording homes in the 100 municipalities around Boston? Arlington and Medford residents are pleased to welcome author Amy Dain to present her report, THE STATE OF ZONING FOR MULTIFAMILY HOUSING IN GREATER BOSTON (June 2019). Learn more about the so-called “paper wall” restricting production, common trends in local zoning, and best practices to increase production going forward. Learn about efforts in Medford and Arlington to increase housing production and affordable housing and how you can get involved. Thursday, July 25, 2019, 7:00 PM at the Medford Housing Authority, Saltonstall Building, 121 Riverside Avenue, Medford. (Parking is available.)

To access the full report, go to: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

The Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, which commissioned the study, provides the following summary of the four principal findings and takeaways:

1) Very little land is zoned for multi-family housing.

For the most part, local zoning keeps new multi-family housing out of existing residential neighborhoods, which cover the majority of the region’s land area.

In addition, cities and towns highly restrict the density of land that is zoned for multi-family use via height limitations, setbacks, and dwelling units per acre. Many of the multi-family zones have already been built out to allowable densities, which mean that although multi-family housing is on the books, it does not exist in practice.

At least a third of the municipalities have virtually no multi-family zoning or plan for growth.

Takeaway: We need to allow concentrated density in multi-family zoning districts that are in sensible locations and allow for incremental growth over a larger area.

2) We are moving to a system of project-by-project decision-making.

Unlike much of the rest of the country, Massachusetts does not require communities to update their zoning on a regular basis and make it consistent with local plans. Although state law ostensibly requires municipalities to update their master plans every ten years, the state does not enforce this provision and most communities lack up-to-date plans.

Instead, the research documents a trend away from predictable zoning districts and toward “floating districts,” project-by-project decision-making, and discretionary permits. Dain found that 57% of multi-family units approved in the region from 2015-2017 were approved by special permit, 22% by 40B (including “friendly” 40B projects), 7% by use variance, and only 14% by “as-of-right” zoning.

There also seems to be a trend toward politicizing development decisions by shifting special permit granting authority to City Council and town meeting. The system emphasizes ad hoc negotiation, which in some cases can achieve a more beneficial project. Yet the overall outcome is a slower, more expensive development process that produces fewer units. Approving projects one by one inhibits the critical infrastructure planning and investments needed to support the growth of an entire district.

Takeaway: We would be better served by a system that retains the benefits of flexibility while offering more speed and predictability.

3) The most widespread trend in zoning for multi-family housing has been to adopt mixed-use zoning.

83 of out of 100 municipalities have adopted some form of mixed-use zoning, most in the last two decades. There is a growing understanding that many people, both old and young, prefer to live in vibrant downtowns, town centers and villages, where they can easily walk to some of the amenities that they want. Malls, plazas and retail areas are increasingly incorporating housing and becoming lifestyle centers.

Yet with few exceptions, the approach to allowing housing in these areas has been cautious and incremental. These projects are only meeting a small portion of the region’s need for housing and often take many years of planning to realize. In addition, the challenges facing the retail sector can make a successful mixed-use strategy problematic. Commercial development tends to meet less opposition than residential development, even in mixed-use areas.

Takeaway: We need more multi-family housing in and around mixed-use hubs, but not require every project to be mixed-use itself.

4) Despite their efforts, communities continue to build much more new housing on their outskirts rather than in their town centers and downtowns.

About half of the communities in the study permitted some infill housing units in their historic centers, but her case studies show that these infill projects are modest in scale and can take up to 15 years to plan and permit.

On the other hand, many more units are getting built in less-developed areas with fewer abutters. This includes conversion of former industrial properties, office parks, and other parcels disconnected from the rest of the community by highways, train tracks, waterways or other barriers. This much-needed housing can be isolated even when dense, and still car-dependent because of limited access to public transportation and lack of walkability.

Takeaway: We need to allow more housing in historic centers as well as incremental growth around those centers. Furthermore, we need to plan an integrated approach to growth districts so that they can be better connected to the community and the region.

This timely report on the question of affordable housing vs. density comes from the California Dept. of Housing & Community Development and mirrors the situation in the region surrounding Arlington MA.

Housing production has not kept up with job and household growth. The location and type of new housing does not meet the needs of many new house- holds. As a result, only one in five households can afford a typical home, overcrowding doubled in the 1990’s, and too many households pay more than they can afford for their housing.

Myth #1

High-density housing is affordable housing; affordable

housing is high-density housing.

Fact #1

Not all high density housing is affordable to low-income families.

Myth #2

High-density and affordable housing will cause too much traffic.

Fact #2

People who live in affordable housing own fewer cars and

drive less.

Myth #3

High-density development strains public services and

infrastructure.

Fact #3

Compact development offers greater efficiency in use of

public services and infrastructure.

Myth #4

People who live in high-density and affordable housing

won’t fit into my neighborhood.

Fact #4

People who need affordable housing already live and work

in your community.

Myth #5

Affordable housing reduces property values.

Fact #5

No study in California has ever shown that affordable

housing developments reduce property values.

Myth #6

Residents of affordable housing move too often to be stable

community members.

Fact #6

When rents are guaranteed to remain stable, tenants

move less often.

Myth #7

High-density and affordable housing undermine community

character.

Fact #7

New affordable and high-density housing can always be

designed to fit into existing communities.

Myth #8

High-density and affordable housing increase crime.

Fact #8

The design and use of public spaces has a far more

significant affect on crime than density or income levels.

See an example of a “case study” of two affordable housing developments in Irvine CA, San Marcos at 64 units per acre.

San Paulo at 25 units per acre.

Both are designed to blend with nearby homes.

WE HAVE WINNERS!

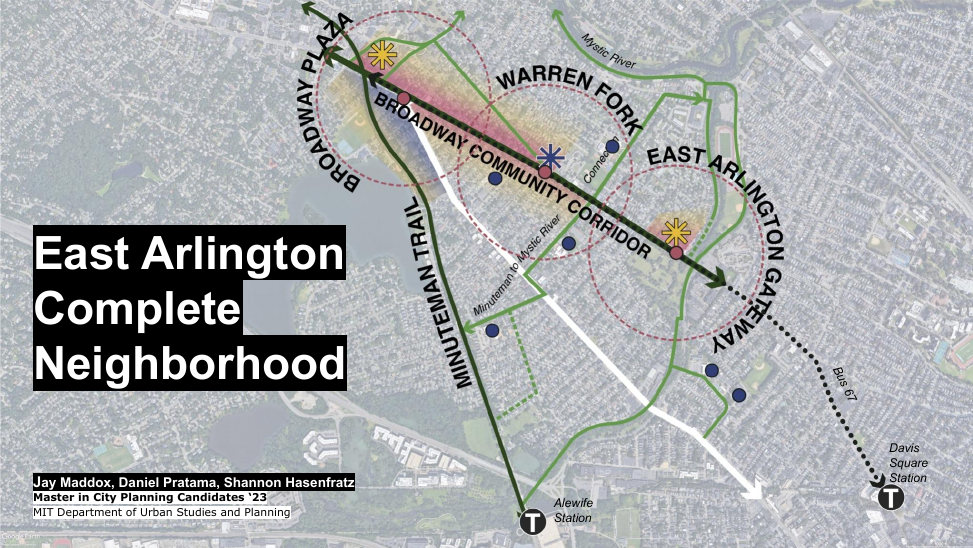

MIT Dept. of Urban Studies and Planning

Jay Maddox maddoxja@mit.edu; Shannon Hasenfratz shasenfr@mit.edu; Daniel Pratama danielcp@mit.edu

Title: EAST ARLINGTON COMPLETE NEIGHBORHOOD

Arlington High School CADD Program

Petru Sofio psofio2024@spyponders.com; Talia Askenazi taskenazi2025@spyponders.com

Title: ENVISION BROADWAY

Winslow Architects

John Winslow john@winslowarchitects.com; Phil Reville philip@winslowarchitects.com; Dolapo Beckley dolapo@winslowarchitects.com

Title: REDEFINING THE BROADWAY CORRIDOR: A 2040+ VISION

Contest Personnel

- Judges: Adria Arch, artist; Caroline Murray, construction project manager; Rachel Zsembery, architect

- Organizer: Barbara Thornton

- Host: Lenard Diggins, Chair, Arlington Select Board

- Sponsor: Civic Engagement Group, Envision Arlington, Town of Arlington MA

- Producer: ACMI

Special thanks

- ACMI production team: Katie Chang, James Milan, Jeff Munro, Jason Audette, Anim Osmani, Jared Sweet, Michael Armanious

- Civic Engagement Group (CEG): Greg Christiana, Len Diggins

- Jenny Raitt- Arlington DHCD Director, for laying the groundwork with the 2019 Broadway Corridor Study

- Jeffrey Levine, MIT DUSP faculty, led the original 2019 Broadway Corridor study team

- Kambiz Vatan & Cinzia Mangano, AHS CADD faculty and community volunteer

- Jane Howard, whose volunteer efforts over many years made possible Vision 2020 and Envision Arlington, leading to CEG and thus making this project possible by giving our town of Arlington the infrastructure, the “DNA”, to make this kind of civic engagement happen.

Background

The Civic Engagement Group (CEG), part of the Town of Arlington’s Envision Arlington network of organizations, is sponsoring the Broadway Corridor Design Competition. Architects, planners, designers and artists from around the region are encouraged to register by April 8, 2022.

This as an opportunity for designers and architects in the region to have some fun exercising real creativity to leapfrog into the post pandemic future and create a 2040+ VISION of what the built environment of a specific neighborhood (our Broadway Corridor area) might look like.

Although the cash prize is small, the pay off will be bragging rights, recognition and a possible opportunity to help shape the upcoming Arlington master plan revision process.

The information: flyer

The plan: Design Competition launch plan

The background data: 2019 Broadway Corridor Study

Register to enter: Sign up information

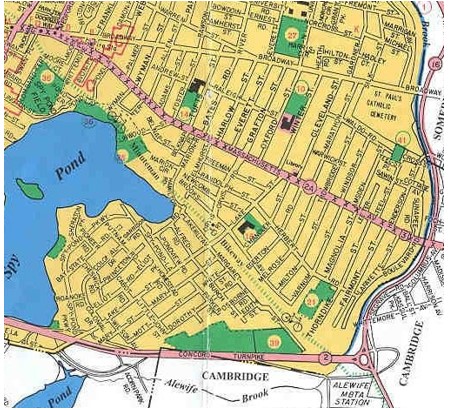

Broadway St. is a major bus route and transit corridor through Arlington to Cambridge. It is close enough to the Alewife MBTA Station to possibly be, at least partially, included in the planning for Arlington’s “transit area” status under the state Dept. of Housing and Community Development’s new guidelines.

by Annie LaCourt

One of the concerns people have about the current MBTA Communities zoning proposal is the effect that the increase in housing will have on the town’s budget. Will the need for new services make demands on our budget we cannot meet without more frequent overrides? Or will the new tax revenues from the new buildings cover the cost of that increase in services?

The simple answers to these questions are

- No: It will not make unmanageable demands on the budget; and

- Yes: the new tax revenue from the multi-family housing anticipated will cover the costs of any new services required.

Adopting the current MBTA Communities zoning proposal may even slow the growth of our structural deficit, as I will show in more detail using as examples some of the more recent multi-family projects that have been built in Arlington.

How Does Our Budget Work and What is the Structural Deficit?

First, some basic facts about finance in Arlington: Like every other community in Massachusetts, Arlington’s property tax increases are limited by Proposition 2.5 to 2.5% of the levy limit each year. What is the levy limit? It’s all of the taxes we are allowed to collect across the whole town, without getting specific approval from the Town’s voters. For FY 23 the levy limit is $135,136,908. $3,271,996 of that is the 2.5% increase we are allowed under the law. But also added to that is $1,202,059 of new growth, which comes from properties whose assessment changed because they were substantially improved–either renovated or by increasing capacity. When we reassess a property that has a new house or building on it, we are allowed to add the new taxes generated by the change in value of the property to the levy limit.

Property taxes make up approximately 75% of the town’s revenue. So – except for new growth – that means that the bulk of our budget can only grow 2.5% a year. Other categories of income like State Aid have a much less reliable growth pattern. If the state has a bad fiscal year, our state aid is likely to remain flat or decrease.

Expenses

On the expense side, our default is a budget to maintain the same level of services year to year. We cap increases in the budgets of town departments by 3.25% and the school budget by 3.5%, save for special education costs which are capped slightly higher.

We also have several major categories of expense that are beyond our control that increase at a greater rate than 2.5%. These include, among other things, funding our pension obligations, health insurance costs and our trash collection contract.

Structural Deficit

This difference between the increase in revenues and the increase in costs is the structural deficit. It’s structural because we can’t cut our way out of it without curtailing services severely and we can’t stop paying for things like pensions and insurance that are contractual obligations.

The question of how MBTA communities zoning will affect this is crucial. So let’s take a deeper dive, first on revenue and then on expenses.

How Will MBTA Communities Affect New Growth?

How MBTA-C zoning will affect new growth depends on what gets built and at what rate. Let’s consider some real world examples:

882 Mass Ave. used to be a single story commercial building. It was assessed at $938,000 and the owner paid approximately $9,887 in taxes annually. It has been rebuilt as a mixed use building with commercial space on the ground level and 22 apartments on 4 floors above. The new assessment is approximately $4,800,000 and the new tax bill is about $54,000.00. That means $45,000 in new growth – new property taxes that will grow at the rate of 2.5% in subsequent years.

Another example is 117 Broadway. The building that used to be at that address was entirely commercial, assessed at $1,050,000 and paid around $11,770 in taxes annually. After being rebuilt as mixed use by the Housing Corporation of Arlington, it is assessed at $3,900,000 and taxed at $43,719. 117 Broadway has commercial on the ground floor and 4 stories of affordable housing above. The new growth for this example is approximately $30,000.

What these examples show, and our assessor believes is a pattern, is that a new mixed use or multi-family building increases the taxes we can collect by as much as 400%, depending on the kinds of housing units.

So we can expect new development under MBTA Communities to increase the levy limit substantially over time, reducing the size and frequency of future tax increases.

How Will This New Housing Affect the Cost of Services?

Of course, with new residents comes a need for additional services. However, town-provided services will be impacted differently. Snow and Ice removal, for example, will not be affected at all – we aren’t adding new roads. Many other services provided by public works are like snow and ice: They would only increase at a faster rate if we added more land area or more town facilities to the base.

Services like public safety and health and human services may see gradual increases in service requests, as more people place more demand on these departments. Right now we have a patrol officer for every 850 or so residents. This means we might need to add a new patrol officer if the population increases by 850 residents. But it’s not clear that a new officer would be needed; it depends on the trends the police department sees in their data. I think of these services as increasing by stair steps: Adding a few, or even a few hundred, residents doesn’t require us to add staff to provide more services. Adding a few thousand might mean we need to add a position but we will have added a great deal to the levy limit before we need to add those positions.

Trash Collection Impact

There is one town service that sees an impact every time we add a new unit of housing – trash collection. The town spends approximately $200 per household on solid waste collection and disposal. As mentioned above, 882 Broadway has 22 new 1 bedroom and studio apartments. When that building was all commercial the businesses paid privately for trash removal. The new trash collection costs will be at least $4,400 annually. It’s possible, however, that the building will need a dumpster and that could cost up to $20,000 annually. Either way the new revenue ($45,000) outstrips the increased costs. The town is working on creative solutions for new buildings to keep this cost as affordable as possible.

What About Schools?

Regardless of new housing construction, our student population ebbs and flows. Families move in with small children who go through the school system. The kids graduate high school but their parents, now in their 50’s or 60’s, don’t move until they are much older and need a different living situation. When they sell their homes, the new owners are likely to be families with children again. We can see a pattern of boom and bust in our school population if we look back. Right now, we are seeing a drop in elementary population as this cycle plays out again. We now have 221 fewer students enrolled in the elementary schools than we did in 2019.

We account for this ebb and flow in the budget. A number of years ago, we set a policy to add a growth factor to the school budget. We increase the budget by 50% of per pupil costs for each new student. Currently that is $8800.00 per student. But the policy works in reverse as well. We reduce the budget by the same amount per child as the student population wanes. We also see increased state aid under chapter 70 when our student population grows and may see reductions if it shrinks.

Will Multifamily Homes Add Students?

The new multi-family housing generated by MBTA communities zoning may add students to our schools – but not as many as you might think. Other large multi-family developments like the Legacy apartments and the new development at the old Brigham site have not added a lot of children to the schools directly. Going back to our two example buildings, 882 Mass Ave is all studio and 1 bedroom units, so we are unlikely to see children living there. Our MBTA communities zoning, however, must by law allow new housing that is appropriate for families. So for planning purposes, it’s best to assume we will see growth in the school population.

So what will the effect of this new housing be on the school population and our budget? Given that the new housing will be built gradually, it’s more likely to stabilize our student population than precipitously increase it. The same will be true for our budget: We will see some increases in the school budget growth factor but also increases in state aid and increases in tax revenue from the new construction.

Conclusions

If we create an MBTA communities zone per the working groups recommendation or something close to that, we will see the effect on our budget over time, not immediately. Even if the zone has a theoretical capacity of 1300 additional units (total capacity minus what is already there) the development of new housing won’t be abrupt. For budget purposes, we project our long range plan five years into the future.

When we get to a year, say FY 2023, the actual state of our budget never looks exactly like the projection created five years earlier. We cannot predict the future very far out. What we can do is look back and see what the effects of previous development have been on our budget, and we can assess the risks of our decisions. Experience tells us that multi-family development doesn’t break the budget or swamp the schools, even when the developments are large. It also tells us that turnover in the population causes ebbs and flows in the school population, regardless of new development. We can say with certainty that multi-family development increases our revenues through new growth, and that past experience has been that that new growth mitigates the need for overrides.

My conclusion is that the new development that will occur if we create a robust zone that allows multi-family development by right, will at worst give us growth in our revenues that keeps pace with any increase in services we need. At best, those new revenues will outstrip the growth in expenses and help mitigate our structural deficit. The risk of allowing this new growth is low, and the rewards are worth it, in the form of new missing middle housing, climate change mitigation, and vibrant business districts fueled by new customers nearby.