A municipality’s master plan is intended to set the vision and start the process of crafting the future of the municipality in regard to several elements, housing, history, culture, open space, transportation, finance, etc. Arlington began a very public discussion about these issues and the development of the Master Plan in 2012. In 2015, after thorough community wide discussion, the Master Plan was adopted by Town Meeting. This year, 2019, the focus is on passing Articles that will amend the current zoning bylaws in order to implement the housing vision that was approved in 2015.

Related articles

(Barbara Thornton, Arlington and Roberta Cameron, Medford)

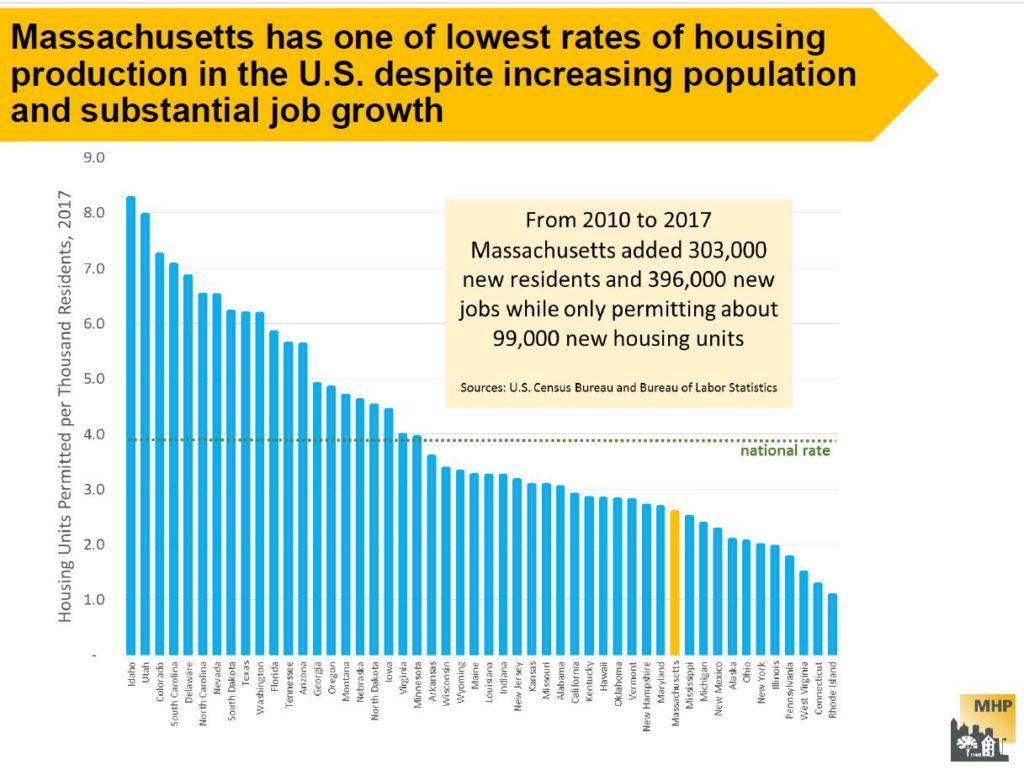

Our communities need more housing that families and individuals can afford. From 2010 to 2017, Greater Boston communities added 245,000 new jobs but only permitted 71,600 new units of housing. Prices are escalating as homebuyers and renters bid up the prices of the limited supply of housing. As a result, one quarter of all renters in Massachusetts now spend more than 50% of their income on housing. (It should be only about 30% of monthly gross income spent on housing costs.) Municipalities have been over-restricting housing development relative to need. The expensive cost of housing not only affects individual households, but also negatively affects neighborhoods and the region as a whole. Lack of affordability limits income diversity in communities. It makes it harder for businesses to recruit employees.

Over the last two years, researcher Amy Dain, commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, has systematically reviewed the bylaws, ordinances, and plans for the 100 cities and towns around Boston to uncover how local zoning affects multifamily housing and why local communities failing to provide enough additional housing to keep the prices from skyrocketing for renters and those who want to purchase homes.

Interested in housing affordability and why the cost of housing is increasing so dramatically to prevent average income residents from affording homes in the 100 municipalities around Boston? Arlington and Medford residents are pleased to welcome author Amy Dain to present her report, THE STATE OF ZONING FOR MULTIFAMILY HOUSING IN GREATER BOSTON (June 2019). Learn more about the so-called “paper wall” restricting production, common trends in local zoning, and best practices to increase production going forward. Learn about efforts in Medford and Arlington to increase housing production and affordable housing and how you can get involved. Thursday, July 25, 2019, 7:00 PM at the Medford Housing Authority, Saltonstall Building, 121 Riverside Avenue, Medford. (Parking is available.)

To access the full report, go to: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

The Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, which commissioned the study, provides the following summary of the four principal findings and takeaways:

1) Very little land is zoned for multi-family housing.

For the most part, local zoning keeps new multi-family housing out of existing residential neighborhoods, which cover the majority of the region’s land area.

In addition, cities and towns highly restrict the density of land that is zoned for multi-family use via height limitations, setbacks, and dwelling units per acre. Many of the multi-family zones have already been built out to allowable densities, which mean that although multi-family housing is on the books, it does not exist in practice.

At least a third of the municipalities have virtually no multi-family zoning or plan for growth.

Takeaway: We need to allow concentrated density in multi-family zoning districts that are in sensible locations and allow for incremental growth over a larger area.

2) We are moving to a system of project-by-project decision-making.

Unlike much of the rest of the country, Massachusetts does not require communities to update their zoning on a regular basis and make it consistent with local plans. Although state law ostensibly requires municipalities to update their master plans every ten years, the state does not enforce this provision and most communities lack up-to-date plans.

Instead, the research documents a trend away from predictable zoning districts and toward “floating districts,” project-by-project decision-making, and discretionary permits. Dain found that 57% of multi-family units approved in the region from 2015-2017 were approved by special permit, 22% by 40B (including “friendly” 40B projects), 7% by use variance, and only 14% by “as-of-right” zoning.

There also seems to be a trend toward politicizing development decisions by shifting special permit granting authority to City Council and town meeting. The system emphasizes ad hoc negotiation, which in some cases can achieve a more beneficial project. Yet the overall outcome is a slower, more expensive development process that produces fewer units. Approving projects one by one inhibits the critical infrastructure planning and investments needed to support the growth of an entire district.

Takeaway: We would be better served by a system that retains the benefits of flexibility while offering more speed and predictability.

3) The most widespread trend in zoning for multi-family housing has been to adopt mixed-use zoning.

83 of out of 100 municipalities have adopted some form of mixed-use zoning, most in the last two decades. There is a growing understanding that many people, both old and young, prefer to live in vibrant downtowns, town centers and villages, where they can easily walk to some of the amenities that they want. Malls, plazas and retail areas are increasingly incorporating housing and becoming lifestyle centers.

Yet with few exceptions, the approach to allowing housing in these areas has been cautious and incremental. These projects are only meeting a small portion of the region’s need for housing and often take many years of planning to realize. In addition, the challenges facing the retail sector can make a successful mixed-use strategy problematic. Commercial development tends to meet less opposition than residential development, even in mixed-use areas.

Takeaway: We need more multi-family housing in and around mixed-use hubs, but not require every project to be mixed-use itself.

4) Despite their efforts, communities continue to build much more new housing on their outskirts rather than in their town centers and downtowns.

About half of the communities in the study permitted some infill housing units in their historic centers, but her case studies show that these infill projects are modest in scale and can take up to 15 years to plan and permit.

On the other hand, many more units are getting built in less-developed areas with fewer abutters. This includes conversion of former industrial properties, office parks, and other parcels disconnected from the rest of the community by highways, train tracks, waterways or other barriers. This much-needed housing can be isolated even when dense, and still car-dependent because of limited access to public transportation and lack of walkability.

Takeaway: We need to allow more housing in historic centers as well as incremental growth around those centers. Furthermore, we need to plan an integrated approach to growth districts so that they can be better connected to the community and the region.

A study by Elise Rapoza and Michael Goodman shows that new housing construction in MA does not have an adverse affect on municipal or school budgets. And when it might, state funding covers the difference. This study contradicts the often heard argument against new housing development, especially multi-family housing, because it, the argument claims, it will have a negative fiscal impact on communities.

In the aggregate, development of new housing offers net fiscal benefit to both municipalities and the state. Additional analysis validates a second study which found that increased housing production does not predict enrollment changes in Massachusetts school districts. In the new study, a distinct minority of municipalities did incur net fiscal burdens—burdens that the net new state tax proceeds associated with the development of new housing are more than sufficient to offset.

This 102 page document is the most recently revised set of recommendations by the Town of Arlington’s Redevelopment Board. The report takes into consideration the comments and information provided over the last few months’ public hearing process. It also incorporates a citizen petition which strengthens the case for increasing permanent affordable housing with the passage of these zoning related Articles. Town Meeting convenes on April 22, 2019.

A few days ago, the Boston Globe ran an article titled “2021 set records in Boston Housing Market. What now?“. It’s not unusual to see stories about housing in the news — the market is highly competitive and the sale prices can be jaw dropping. Jaw dropping can take several forms: from the new (and used) homes that sell for over two million dollars, to the amount of money that someone will pay to purchase a small post-war cape (around $900,000, give or take).

According to the globe article, the Greater Boston Association of Realtors estimates that the median price of a single family homes in the Boston area rose 10.5% in 2021, to $750,000. Arlington is comfortably in the upper half of this median: according to our draft housing production plan the median sale price of our single family homes was $862,500 in 2020, and rose to $960,000 in the first half of 2021 (see page 39).

In June 2021, I got myself into a habit of sampling real estate sales listed in the Arlington Advocate, and compiling them into a spreadsheet. My observations are generally consistent with the sources cited above; Arlington’s housing is expensive and it’s appreciated rapidly, particularly in the last 6–10 years. It’s a great time for existing owners, but less so if you’re in the market for your first home.

We’re actually facing two problems, which are related but not identical. The first is high cost, which creates financial stress and a barrier to entry (though it is a boon for those who sell). The second problem is quantity; there are regional and national housing shortages, and that contributes to high prices and bidding wars.

Addressing these challenges will require collective effort on behalf of all communities in the metro area; this is a regional problem and we’ll all have to pitch in. There isn’t a single recipe for what “pitching in” means, but here are some for what communities can do.

First, produce more affordable housing. Affordable housing is a complex regulatory subject, but it basically boils down to two things: (1) the housing is reserved for households with lower incomes than the area as a whole, and (2) there’s a deed restriction (or similar) that prevents it from being sold or rented at market rates. Affordable housing usually costs more to produce than it generates in income, and the difference has to be made up with subsidies. It takes money.

Second, simply produce more housing. This is the obvious way to address an absolute shortage in the number of dwellings available. Some communities have set goals for housing production. Under the Walsh administration, Boston set a goal of producing 69,000 new housing units by 2030. Somerville’s goal is 6000 new housing units, and Cambridge’s is 12,500 (page 152 of pdf). To the best of my knowledge, Arlington has not set a numeric housing production goal, but it’s something I’d like to see us do.

Finally, communities could be more flexible with the types of housing they allow. Arlington is predominantly zoned for single- and two-family homes. The median sale price of our single family homes was $960,000 during the first half of 2021, and a large portion of that comes from the cost of land. That’s the reality we have, and the existing housing costs what it costs. So, we might consider allowing more types of “missing middle” housing, where the per dwelling costs tend to be lower: apartments, town houses, triple-deckers, and the like.

Of course, this assumes that our high cost of housing is a problem that needs to be solved; we could always decide that it isn’t. In the United States, home ownership is seen as a way to build equity and wealth. It’s certainly been fulfilling that objective, especially in recent years.

WE HAVE WINNERS!

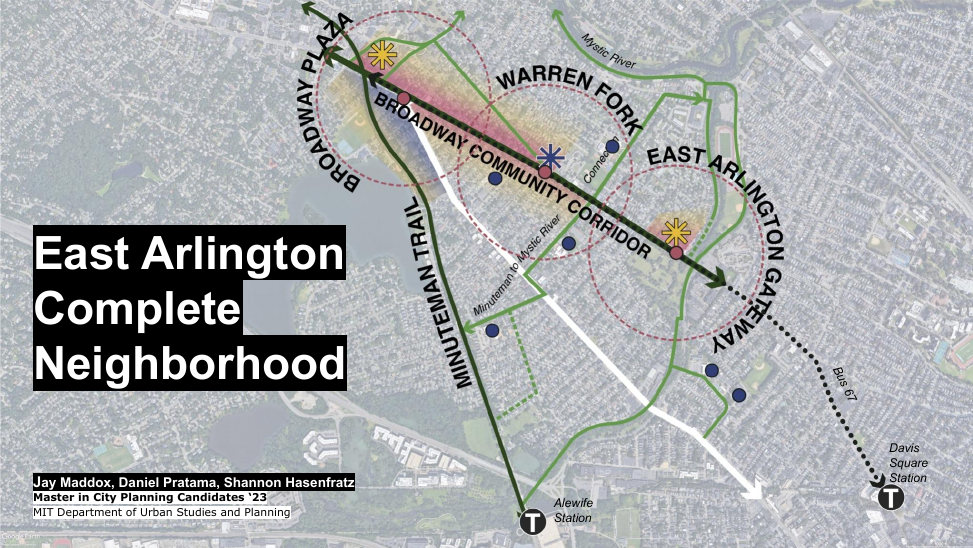

MIT Dept. of Urban Studies and Planning

Jay Maddox maddoxja@mit.edu; Shannon Hasenfratz shasenfr@mit.edu; Daniel Pratama danielcp@mit.edu

Title: EAST ARLINGTON COMPLETE NEIGHBORHOOD

Arlington High School CADD Program

Petru Sofio psofio2024@spyponders.com; Talia Askenazi taskenazi2025@spyponders.com

Title: ENVISION BROADWAY

Winslow Architects

John Winslow john@winslowarchitects.com; Phil Reville philip@winslowarchitects.com; Dolapo Beckley dolapo@winslowarchitects.com

Title: REDEFINING THE BROADWAY CORRIDOR: A 2040+ VISION

Contest Personnel

- Judges: Adria Arch, artist; Caroline Murray, construction project manager; Rachel Zsembery, architect

- Organizer: Barbara Thornton

- Host: Lenard Diggins, Chair, Arlington Select Board

- Sponsor: Civic Engagement Group, Envision Arlington, Town of Arlington MA

- Producer: ACMI

Special thanks

- ACMI production team: Katie Chang, James Milan, Jeff Munro, Jason Audette, Anim Osmani, Jared Sweet, Michael Armanious

- Civic Engagement Group (CEG): Greg Christiana, Len Diggins

- Jenny Raitt- Arlington DHCD Director, for laying the groundwork with the 2019 Broadway Corridor Study

- Jeffrey Levine, MIT DUSP faculty, led the original 2019 Broadway Corridor study team

- Kambiz Vatan & Cinzia Mangano, AHS CADD faculty and community volunteer

- Jane Howard, whose volunteer efforts over many years made possible Vision 2020 and Envision Arlington, leading to CEG and thus making this project possible by giving our town of Arlington the infrastructure, the “DNA”, to make this kind of civic engagement happen.

Background

The Civic Engagement Group (CEG), part of the Town of Arlington’s Envision Arlington network of organizations, is sponsoring the Broadway Corridor Design Competition. Architects, planners, designers and artists from around the region are encouraged to register by April 8, 2022.

This as an opportunity for designers and architects in the region to have some fun exercising real creativity to leapfrog into the post pandemic future and create a 2040+ VISION of what the built environment of a specific neighborhood (our Broadway Corridor area) might look like.

Although the cash prize is small, the pay off will be bragging rights, recognition and a possible opportunity to help shape the upcoming Arlington master plan revision process.

The information: flyer

The plan: Design Competition launch plan

The background data: 2019 Broadway Corridor Study

Register to enter: Sign up information

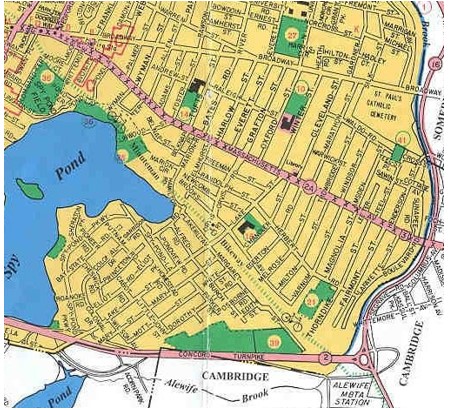

Broadway St. is a major bus route and transit corridor through Arlington to Cambridge. It is close enough to the Alewife MBTA Station to possibly be, at least partially, included in the planning for Arlington’s “transit area” status under the state Dept. of Housing and Community Development’s new guidelines.

Article 1 in a series on the Arlington, MA master planning process. Prepared by Barbara Thornton

Arlington, located about 15 miles north west of Boston, is now developing a master plan that will reflect the visions and expectations of the community and will provide enabling steps for the community to move toward this vision over the next decade or two. Initial studies have been done, public meetings have been held. The Town will begin in January 2015 to pull together the vision for its future as written in a new Master Plan.

In developing a new master plan, the Town of Arlington follows in the footsteps laid down thousands of years ago when Greeks, Romans and other civilizations determined the best layout for a city before they started to build. In more recent times, William Penn laid out his utopian view of Philadelphia with a gridiron street pattern and public squares in 1682. Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant developed the hub and spoke street plan for Washington DC in 1798. City planning started with new cities, relatively empty land and a “master builder” typically an architect, engineer or landscape architect commissioned by the land holders to develop a visionary design.

In the 1900’s era of Progressive government in America, citizens sought ways to reach a consensus on how their existing cities should evolve. State and federal laws passed to help guide this process, seeing land use decisions as more than just a private landowner’s right but rather a process that involved improving the health and wellbeing of the entire community. While the focus on master planning was and still is primarily physical, 21st century master planners are typically convened by the local municipality, work with the help of trained planners and architects and rely heavily on the knowledge and participation of their citizenry to reflect a future vision of the health and wellbeing of the community. This vision is crafted into a Master Plan. In Arlington the process is guided by Carol Kowalski, Director of Planning and Community Development, with professional support from RKG Associates, a company of planners and architects and with the vision of the Master Planning advisory committee, co-chaired by Carol Svenson and Charles Kalauskas, Arlington residents, and by the citizens who share their concerns and hopes with the process as it evolves. This happens through public meetings, letters, email, and surveys. The most recent survey asks residents to respond on transportation modes and commuting patterns

We all do planning. Starting a family, a business or a career, we lay out our goals and assume the steps necessary to accomplish these goals and we periodically revise them as necessary. The same thing is true for cities. Based on changes in population, economic development, etc. cities, from time to time, need to revise their plans. In Massachusetts the enabling acts for planning and zoning are here http://www.mass.gov/hed/community/planning/zoning-resources.html. The specific law for Massachusetts is MGL Ch. 41 sect. 81D. This plan, whether called a city plan, master plan, general plan, comprehensive plan or development plan, has some constant characteristics independent of the specific municipality: focus on the built environment, long range view (10-20 years), covers the entire municipality, reflects the municipality’s vision of its future, and how this future is to be achieved. Typically it is broken out into a number of chapters or “elements” reflecting the situation as it is, the data showing the potential opportunities and concerns and recommendations for how to maximize the desired opportunities and minimize the concerns for each element.

Since beginning the master planning process in October, 2012, Arlington has had a number of community meetings (see http://vod.acmi.tv/category/government/arlingtons-master-plan/ ) gathering ideas from citizens, sharing data collected by planners and architects and moving toward a sense of what the future of Arlington should look like. The major elements of Arlington’s plan include these elements:

1. Visions and Goals http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19829

2. Demographic Characteristics http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19838

3. Land Use http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19834

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19825

4. Transportation http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19830

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19822

5. Economic Development http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19837

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19828

6. Housing http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19835

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19826

7. Open Space and Recreation http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19832

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19824

8. Historic and Cultural Resources http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19836

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19827

9. Public Facilities and Services http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19831

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19823

10. Natural Resources

Working paper: http://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showdocument?id=19824

The upcoming articles in this series will focus on each individual element in the Town of Arlington’s Master Plan.

It’s the time of year when folks in Arlington are taking out nomination papers, gathering signatures, and strategizing on how to campaign for the town election on Saturday April 1st. The town election is where we choose members of Arlington’s governing institutions, including the Select Board (Arlington’s executive branch), the School Committee, and — most relevantly for this post — Town Meeting.

If you’re new to New England, Town Meeting is an institution you may not have heard of, but it’s basically the town’s Legislative Branch. Town Meeting consists of 12 members from each of 21 Precincts, for 252 members total. Members serve three-year terms, with one-third of the seats up for election in any year, so that each precinct elects four representatives per year (perhaps with an extra seat or two, as needed to fill vacancies). For a deeper dive, Envision Arlington’s ABC’s of Arlington Government gives a great overview of Arlington’s government structure.

As our legislative branch, town meeting’s powers and responsibilities include:

- Passing the Town’s Operating Budget, which details planned expenses for the next year.

- Approving the town’s Capital Budget, which includes vehicle and equipment purchases, playgrounds, and town facilities.

- Bylaw changes. Town meeting is the only body that can amend the towns bylaws, including ones that affect housing — what kinds can be built, how much, and where.

Town Meeting is an excellent opportunity to serve your community, and to learn about how Arlington and its municipal government works. Any registered voter is eligible to run. If this sounds like an interesting prospect, we encourage you to run! Here’s what you’ll need to do:

- Have a look at the town’s Information for new and Prospective Town Meeting Members.

- Contact the Town Clerk’s office to get a set of nomination papers. You’ll need to do this by 5:00 PM February 12th, 2025 at the latest.

- Gather signatures. You’ll need signatures from at least ten registered voters in your precinct to get on the ballot (it’s always good to get a few extra signatures, to be safe).

- Return your signed nomination papers to the Clerk’s office by February 14, 2025 at 5:00 PM.

- Campaign! Get a map and voter list for your precinct, knock on doors, and introduce yourself. (Having a flier to distribute is also helpful.)

- Vote on Saturday April 5th, and wait for the results.

Town Meeting traditionally meets every Monday and Wednesday at 8:00 PM, starting on the 4th Monday in April (which is April 28th this year), and lasting until the year’s business is concluded (typically a few weeks).

If you’d like to connect with an experienced Town Meeting Member about the logistics of campaigning, or the reality of serving at Town Meeting, please email info(AT)equitable-arlington.org and we’d be happy to make an introduction.

During the past few years, Town Meeting was our pathway to legalizing accessory dwelling units, reducing minimum parking requirements, loosening restrictions on mixed-use development in Arlington’s business districts, and adopting multi-family zoning for MBTA Communities. Aside from being a rewarding experience, it’s a way to make a difference!

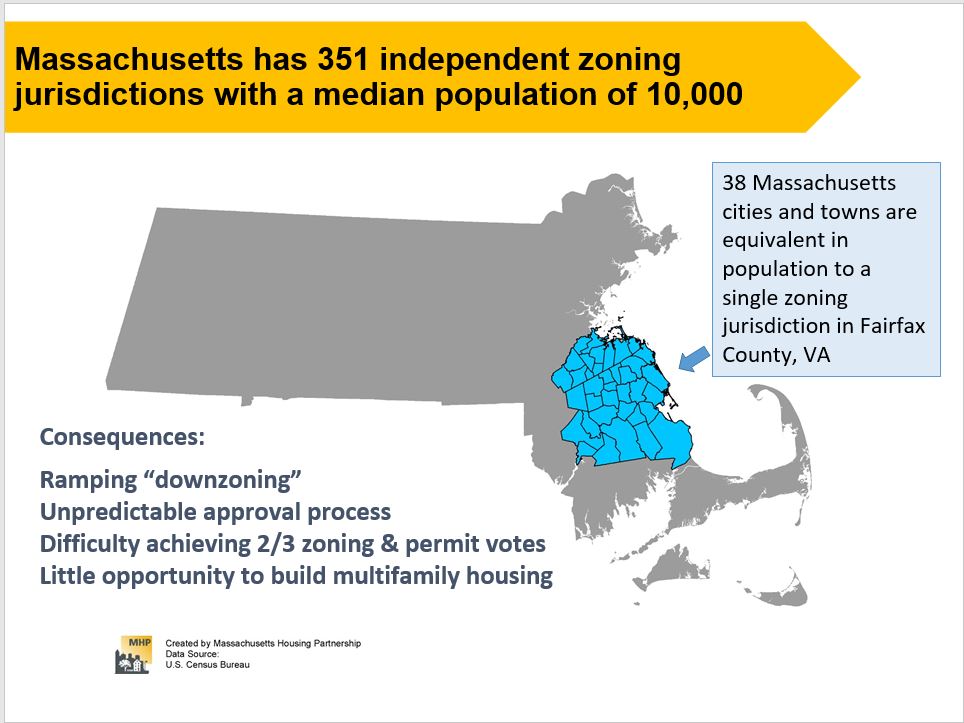

Data in a Mass Housing Partnership report shows how far behind the Boston metropolitan area has fallen in meeting the housing needs of its citizens. There are four primary categories for measuring the inadequacies: 1. Availability, 2. Affordability, 3. L0cation and Mobility and 4. Equitability. See the full report for more data and examples. Two slides are shown below.