The presentation, dated March 11, 2019, includes slides used to present the information necessary to understand the rationale for zoning changes, the location of the zoning areas under consideration and the charts, tables and maps that help describe the situation. The proposed zoning changes, especially articles 6, 7, 8, 11 and 16, only cover changes affecting about 7% of the Town, those parts of the Town that are currently zoned R4-R7 and the B zoning districts.

Related articles

by Steve Revilak

On Tuesday August 6, 2024, Governor Healey signed the Affordable Homes Act (H.4977) into law. It’s a significant piece of legislation that will take positive strides toward addressing our state’s housing crisis. At 181 pages, the Affordable Homes Act is a lengthy bill, but the things it does generally fall into three categories: funding, changes to state law, and changes to state agencies.

The act authorizes more than five billion dollars to fund the creation, maintenance, and preservation of housing. This includes $425M to housing authorities and local housing initiatives (including $2.5M for the Arlington Housing Authority), $60M to assist homeowners or tenants with a household member with blindness or severe disabilities, $70M for community-based efforts to develop supportive housing for persons with disabilities, and $100M to expand opportunities for first-time homebuyers.

The Affordable Homes Act makes several changes to Massachusetts zoning laws, including the legalization of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) statewide. ADUs, also known as “granny flats” or “in-law apartments,” are a cost-effective way to add new housing, and they’re typically used to provide living quarters for relatives or caretakers, or to generate rental income for homeowners. ADUs are now allowed in all single-family zones in Massachusetts, by right, without the need for a discretionary permit. Arlington has been a leader in this area, having passed an ADU bylaw in 2021, and it’s great to see this option extended throughout the Commonwealth.

Finally, the Affordable Homes Act makes a number of changes to state agencies, especially the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC). The Act establishes a new Office of Fair Housing within the EOHLC, to “advance the elimination of housing discrimination.” The Fair Housing office will provide periodic reports on progress towards achieving this goal. EOHLC is also charged with creating and implementing a state-wide housing plan that will consider supply and demand, affordability, challenges unique to different regions of the state, and an analysis of local zoning laws.

While our legislators deserve kudos for putting this package together, they also deserve kudos for what they left out. More than three hundred amendments were filed during House deliberations, and a number of them were intended to weaken the multi-family housing requirements of the MBTA Communities Act. For example, one amendment, simply titled “Technical Correction” would have rewritten the transit community definitions, in order to reduce the housing requirements for Milton. We are heartened that our legislators did not go along with such shenanigans.

The cost of building a residential unit, single or multi-family, correlates directly, if not precisely, with its cost to resident tenants or owners. The following study and data (using Assessor’s data) demonstrates that higher density housing is more affordable than single-family housing. Whether you look at the median cost of all housing across the Town or the unit costs of the newer, more expensive, apartments built in the last decade, density yields lower prices. The town wide median is $438,900 per unit.

The newest projects (420-440 Mass Ave., Brigham Square and Arlington 360) range from $249k per unit to $412K per unit. These three developments alone contributed 414 new units of housing to the Town.

Discussions of “affordability” represents a spectrum of terms. Units can be affordable because zoning and market conditions allow the units to be built for less money than a single family home. Or they can be affordable because the builder has received subsidies that reduce the cost. Or they can be affordable, as in the case of inclusionary zoning, because the permission to build is contingent on at least some of the units being “permanently” (99 years) available to qualified tenants or buyers based on legal restrictions.

Minneapolis is the most recent governmental entity to disrupt the almost 110 year old idea of local zoning in America by overriding single family zoning. Zoning was developed in the the early 1900’s to control property rights and, in part, to limit access to housing by race. These early laws were upheld by the courts in the 1930’s and the use of zoning to control private property for the interests of the majority became common. Houston Texas did not adopt zoning, an outlier in the nation.

But recently governments are rethinking zoning in light of evidence of exclusionary practices including racism and inadequate supplies of affordable housing. In July Oregon’s legislature voted to essentially ban single family zoning in the state.

Most recently, in the end of July, Minneapolis became the first city this century to remove single family zoning, allowing two family housing units to enter any single family zone as of right. According to the Bloomberg News article, the city took action to remedy the untenable price increases do to single family homes taking a disproportionate amount of city land and services. They hope a wider range of housing, and more housing, will reduce housing costs in the future.

Read the full story from Bloomberg News.

A municipality’s master plan is intended to set the vision and start the process of crafting the future of the municipality in regard to several elements, housing, history, culture, open space, transportation, finance, etc. Arlington began a very public discussion about these issues and the development of the Master Plan in 2012. In 2015, after thorough community wide discussion, the Master Plan was adopted by Town Meeting. This year, 2019, the focus is on passing Articles that will amend the current zoning bylaws in order to implement the housing vision that was approved in 2015.

(Contributed by HCA Board Member Laura Wiener, and Executive Director Erica Schwarz)

The Housing Corporation of Arlington (HCA), the Town’s non-profit housing developer, is excited to create a new development on Sunnyside Ave with 43 new affordable homes. The homes will be a diverse mix of sizes and serve people of different incomes, all under 60% of the area median income. Arlington and the entire Greater Boston region have a severe shortage of affordable housing, which this project will help to address. Arlington’s Master Plan, Housing Plan, and Housing Trust Action Plan all acknowledge the need to create significantly more affordable housing.

The HCA’s new Sunnyside Ave proposal is located just off Broadway, near the Alewife Brook DCR Greenway and the Somerville line; it’s a great location near a supermarket, bus lines, and a modest walk to Davis Square. Currently, the site is a dilapidated former auto body shop. The proposal is designed to meet the specific needs of HCA’s residents and the Arlington community. The development will be Passive House certified. It includes 21 vehicle parking spaces, approximately 70 bike parking spaces, and a 2nd floor roof garden for tenants to enjoy. The development also includes a community room that the HCA will share with other local groups. The project will also add a sidewalk on Sunnyside Ave where there currently isn’t one. HCA owns the site and expects to start seeking zoning approval in the spring.

Building affordable housing is a long and complicated process, due to the permitting process plus the number and complexity of funding sources needed. The state’s Department of Housing and Community Development receives many more requests than they can fund in every funding round. We expect to complete the permitting process in 2023, secure our financing by the end of 2024, and start construction in early 2025. With an expected construction timeline of around one year, HCA expects to see tenants moving into the building in spring, 2026. A public forum on the project is anticipated in the coming months. Given the complicated funding and permitting challenges, your monetary and public support of our new development on Sunnyside Ave would be appreciated.

The Housing Corporation of Arlington is a non-profit, community-based developer and owner of affordable housing in Arlington. It owns 150 units of affordable rental housing in all parts of town. The units are occupied by a diverse mix of families and individuals. HCA has been purchasing, rehabilitating, and building new housing since 2000, and also provides social service programs to support family stability and build community connection and engagement. Every week, HCA staff help local families who are struggling with the extreme cost of housing, making the creation of more affordable homes both urgent and important.

The staff, board of directors, and the more than 1,000 tenants, donors, and members who make up the HCA organization are very excited about this opportunity to expand Arlington’s portfolio of affordable housing. Our most recent projects included three newly constructed buildings—two in Downing Square (Lowell Street) and a mixed-use property shared with “Arlington Eats” on Broadway. To learn more about HCA or apply for housing, go to: https://www.housingcorparlington.org.

Thanks to so many of you who came out Monday evening for the demonstration in support of the MBTA Communities proposal before the Arlington Redevelopment Board meeting! Over 20 people were there – a substantial and notable showing, especially on such short notice. Paulette Schwarz took some photos of the demonstration early in the evening which she kindly shared with us.

This 102 page document is the most recently revised set of recommendations by the Town of Arlington’s Redevelopment Board. The report takes into consideration the comments and information provided over the last few months’ public hearing process. It also incorporates a citizen petition which strengthens the case for increasing permanent affordable housing with the passage of these zoning related Articles. Town Meeting convenes on April 22, 2019.

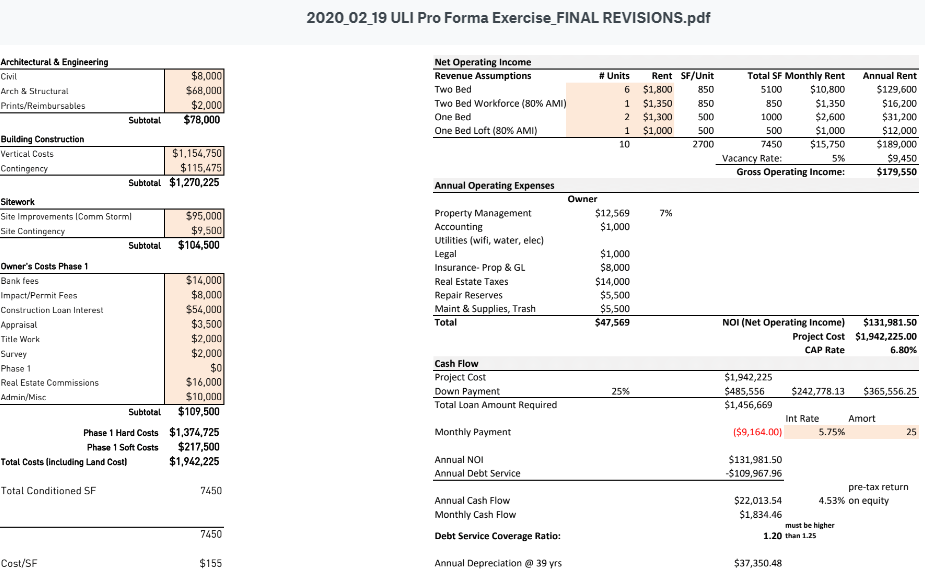

Dave Weinstock, an Arlington resident interested in affordable housing wondered about the concept of “developer math”. The math involved in planning an affordable housing projects is a problem that needs to get solved in order to have anything built here in Arlington, or anywhere. This topic comes up frequently in community discussions about the need for more housing.

Questions are raised around:

- 1- Why build so many units vs. smaller buildings

- 2- Why parking is costly and inefficient use of land

- 3- Why can’t more affordable or all affordable units be built?

- 4- The cost of subsidizing affordable units and how that may translate to higher rental rates/costs, etc.

Dave found a great Architecture and Development firm in Atlanta (Kronberg Urbanists + Architects, based in Atlanta GA) that lays out a nice presentation, includes sample proformas, and real life scenarios that may help us understand this piece of the puzzle better when evaluating any project and how developers may be incented to build certain types of projects or do certain types of work.

Here is a link, reformatted to be within this website, to the presentation, showing the varieties of choices, costs, formulas and outcomes developers consider before deciding if the project can be built: https://equitable-arlington.org/developer-math_kua_071420/

Much of our hope for more affordable housing depends on the market forces of capitalism and the willingness of developers to build for good, not just for profit. But the developers must be able to cover their costs. Many communities are highly skeptical of developers, assuming the community will get tricked, the developer will get greedy and the promised housing will be a disappointment. Trust is needed. But so is verification. We all need to learn the developer math.

What are the math factors that a developer considers before deciding to build affordable housing?

Here is a link to the original presentation. https://www.kronbergua.com/post/mr-mu-let-s-talk-about-math