A municipality’s master plan is intended to set the vision and start the process of crafting the future of the municipality in regard to several elements, housing, history, culture, open space, transportation, finance, etc. Arlington began a very public discussion about these issues and the development of the Master Plan in 2012. In 2015, after thorough community wide discussion, the Master Plan was adopted by Town Meeting. This year, 2019, the focus is on passing Articles that will amend the current zoning bylaws in order to implement the housing vision that was approved in 2015.

Related articles

The citizen participation process including presentations, discussions, public hearings, letters and comments has been long and arduous. The issues are complicated and sometimes feelings run high. In such situations, there can be a feeling that citizens have not been heard. This document, “Guide to Zoning Amendments Related to Multifamily Uses and Mixed-Use“, summarizes many of the issues that have been raised and the changes that have been made in the zoning Articles as a result of the citizen participation in the public review process. Citizens have been heard.

The presentation, dated March 11, 2019, includes slides used to present the information necessary to understand the rationale for zoning changes, the location of the zoning areas under consideration and the charts, tables and maps that help describe the situation. The proposed zoning changes, especially articles 6, 7, 8, 11 and 16, only cover changes affecting about 7% of the Town, those parts of the Town that are currently zoned R4-R7 and the B zoning districts.

A few days ago, the Boston Globe ran an article titled “2021 set records in Boston Housing Market. What now?“. It’s not unusual to see stories about housing in the news — the market is highly competitive and the sale prices can be jaw dropping. Jaw dropping can take several forms: from the new (and used) homes that sell for over two million dollars, to the amount of money that someone will pay to purchase a small post-war cape (around $900,000, give or take).

According to the globe article, the Greater Boston Association of Realtors estimates that the median price of a single family homes in the Boston area rose 10.5% in 2021, to $750,000. Arlington is comfortably in the upper half of this median: according to our draft housing production plan the median sale price of our single family homes was $862,500 in 2020, and rose to $960,000 in the first half of 2021 (see page 39).

In June 2021, I got myself into a habit of sampling real estate sales listed in the Arlington Advocate, and compiling them into a spreadsheet. My observations are generally consistent with the sources cited above; Arlington’s housing is expensive and it’s appreciated rapidly, particularly in the last 6–10 years. It’s a great time for existing owners, but less so if you’re in the market for your first home.

We’re actually facing two problems, which are related but not identical. The first is high cost, which creates financial stress and a barrier to entry (though it is a boon for those who sell). The second problem is quantity; there are regional and national housing shortages, and that contributes to high prices and bidding wars.

Addressing these challenges will require collective effort on behalf of all communities in the metro area; this is a regional problem and we’ll all have to pitch in. There isn’t a single recipe for what “pitching in” means, but here are some for what communities can do.

First, produce more affordable housing. Affordable housing is a complex regulatory subject, but it basically boils down to two things: (1) the housing is reserved for households with lower incomes than the area as a whole, and (2) there’s a deed restriction (or similar) that prevents it from being sold or rented at market rates. Affordable housing usually costs more to produce than it generates in income, and the difference has to be made up with subsidies. It takes money.

Second, simply produce more housing. This is the obvious way to address an absolute shortage in the number of dwellings available. Some communities have set goals for housing production. Under the Walsh administration, Boston set a goal of producing 69,000 new housing units by 2030. Somerville’s goal is 6000 new housing units, and Cambridge’s is 12,500 (page 152 of pdf). To the best of my knowledge, Arlington has not set a numeric housing production goal, but it’s something I’d like to see us do.

Finally, communities could be more flexible with the types of housing they allow. Arlington is predominantly zoned for single- and two-family homes. The median sale price of our single family homes was $960,000 during the first half of 2021, and a large portion of that comes from the cost of land. That’s the reality we have, and the existing housing costs what it costs. So, we might consider allowing more types of “missing middle” housing, where the per dwelling costs tend to be lower: apartments, town houses, triple-deckers, and the like.

Of course, this assumes that our high cost of housing is a problem that needs to be solved; we could always decide that it isn’t. In the United States, home ownership is seen as a way to build equity and wealth. It’s certainly been fulfilling that objective, especially in recent years.

(published June, 2019)

Overview

To solve the extraordinarily large deficit in housing for the greater Boston region, over 180,000 units of new housing should come on line in the next few years. This deficit is the result of a rapid expansion in in-migration due to new job creation, with no commensurate increase in housing production for the people taking those new jobs.

The report concludes that zoning is a primary culprit in restricting the development of an adequate housing supply, creating a “PAPER WALL” keeping out newcomers. The cost of this inadequate supply is a huge demand for housing which, in turn, bids up the price for available housing. The following “culprits” are considered: inadequate land area zoned for multi-family housing; low density zoning; age restrictions and bedroom restrictions; excessive parking requirements; mixed use requirements and approval processes. Alternative zoning models are suggested.

Elements such as “Approval Process”, “Mixed Use”, “Village Centers vs Isolated Parcels” and “Building Up or Building Out” are considered.

Researcher Amy Dain reports on two years of research into the regulations, plans and permits in the 100 cities and towns surrounding Boston. The research was commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance and funded collaboratively with: Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association, Home Builders & Remodelers Association of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Association of Realtors, Massachusetts Housing Partnership, MassHousing, and Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

For the full report see: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

For a power point slide presentation see: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/04/DainZoningMFPresentationShare2019.pdf

For the Executive Summary see: https://equitable-arlington.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/June-2019-Multi-Family-Housing-Report_Executive-Summary.pdf

Welcome to the redesigned Equitable Arlington website! We know that Arlington values openness and diversity, a greener future, and vibrant neighborhoods and downtowns—but our current zoning is holding us back. We’re advocating for change because we recognize that the choices we make on zoning and housing policy are key to living those values. We are committed to strengthening our community through respectful dialogue and by listening to our neighbors. Our aim with this site redesign is to share accurate and relevant information to help inform such conversations.

With this redesigned site we have:

- Answered some of the most common questions that have come up in our conversations with other residents.

- Created a zoning dictionary with explanations of many of the terms that pepper zoning discussions.

- Gathered a list of resources, where you’ll find everything from short explainer videos to detailed research

- Developed a history of zoning timeline that shows how Arlington’s history fits into the larger context of government actions.

If you’re not familiar with us, I hope you’ll take a minute to read our mission and why our work matters. I also hope you’ll scroll through to meet us, see some of our smiling faces, and read in our own words why we do this work. We’re renters and homeowners, long time residents and newcomers to town who come to this work with a variety of viewpoints and lived experiences!

We believe Arlington can be a leader in the greater Boston area by the choices we make to create more equitable housing policy. Our local actions have effects that go beyond our borders. Arlington has recognized our power to make an impact and has been a regional leader on many issues.

We can channel this same energy and our values to make sure Arlington has the vibrant sustainable and equitable future we all want. To succeed, we need engaged residents who understand the issues, who can balance competing interests, and who are willing to do the necessary hard work. Please join us in building a more equitable Arlington!

Two weeks ago, I helped to organize a precinct meeting for residents and town meeting members. During the meeting, we got into a discussion about public open spaces, how the town funds their upkeep, and whether having more commercial tax revenue might provide additional funding for parks and recreation.

As I discussed in an earlier post, only about 5.6% of Arlington’s is zoned for commercial uses, and that limits the amount of commercial property tax revenue we can generate. Commercial property tax revenue is sometimes referred to as “CIP”, which stands for “Commercial, Industrial, and Personal”. Commercial and Industrial refer to property taxes on land and buildings that are respectively used for commercial and industrial uses. Personal tax is tax on the value of equipment that’s owned and used by a business for the purpose of carrying out whatever their business is. This could include things like desks, display fixtures, cooking equipment, fork lifts, and the like.

In 2020, Arlington’s CIP levy was 5.45%, meaning that 5.45% of our property tax revenue came from Commercial, Industrial, and Property tax revenue. Breaking this down further, 4.2% was commercial ($5,562,528 tax levy), 0.2% was industrial ($278,351 tax levy), and 1.1% was personal ($1,423,117 tax levy). The town’s total 2020 tax levy was $133,350,155. This data comes from MassDOR’s Division of Local Services, and I’ll provide more specific sources in the “References” section of this post.

A CIP levy of 5.45% is low (compared with other communities in the commonwealth), and occassionaly folks like to talk talk about how to raise it. Which is to say, we about how to raise the ratio of commercial to residential taxes. I moved to Arlington in 2007, when our CIP levy was 5.37%. This increased in subsequent years, peaking at 6.26% in 2013, and has been gradually decreasing since. Recall that 2008 was the year the housing market crashed, and the “great recession” began. The value of Arlington’s residential property fell, but the value of business properties was relatively stable in comparison. Thus, our CIP percentage got a boost for a couple of years.

Tax levies (the amount of tax collected) are a direct reflection of the tax basis (the assessed value of property). I’m going to shift from talking about the former to talking about the latter, because that will lead nicely to a discussion about property wealth. Which is to say, the aggregate value of property assessments in town.

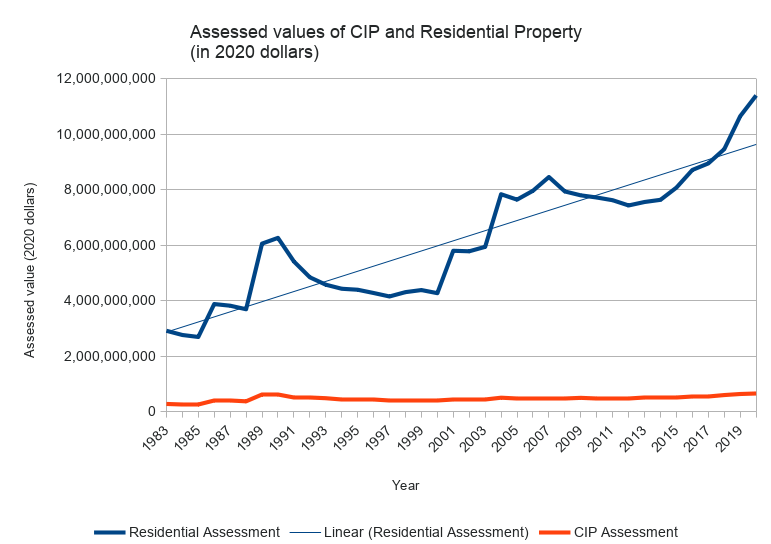

Here’s a chart showing Arlington’s net CIP and residential property values, from 1983–2020, adjusted to 2020 dollars. (This is similar to the chart that appears on page 102 of Arlington’s Master plan, but for a longer period of time).

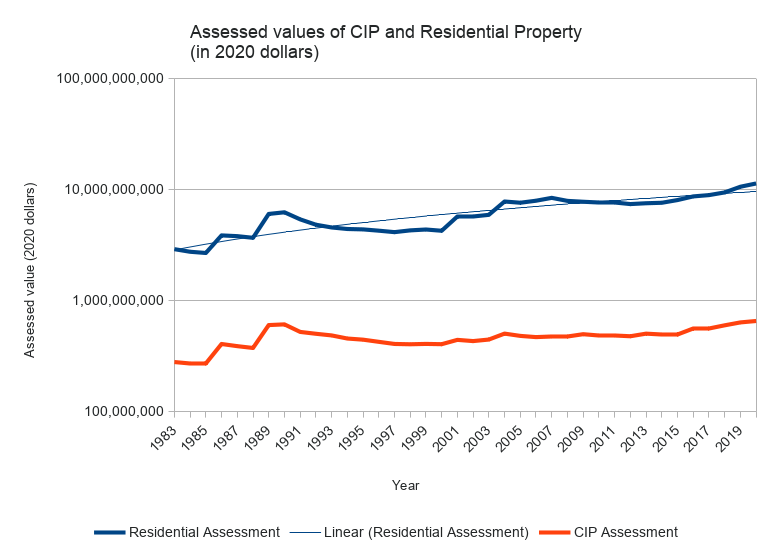

Generally speaking, the value of Arlington’s residential property has appreciated considerably, and there’s a widening gap between our residential and CIP assessments (in terms of raw dollars). Because the gap is so large, it’s helpful to see it on a log scale.

Viewed this way, the curvatures are generally similar, but residential property wealth is rising faster than business property wealth.

In summary, there are three reasons why our CIP is as low as it is: (1) a limited amount of land where one can run a business, (2) the value of residential property is appreciating faster than the value of business property, and (3) occasionally business properties are converted to residential (perhaps with the residential property being worth more than the former business property). That’s not to say we can’t improve the commercial tax base. We can, but we will have to think about what and where, and how to compete with a generally competitive residential market.

References

- MassDOR Division of Local Services reports

- DOR Query Tool for Municipal Property Assessments

- DOR Query Tool for Municipal Tax Levies

- Spreadsheet of Arlington Property Assessments, 1983–2020. Data obtained from MassDOR, with calculations added to adjust for inflation.

- Spreadsheet of Massachusetts Property assessments for 2020. Data obtained from MassDOR.

(Updated 7/2/2020, to add log scale graph and revise conclusion.)

Why Is This Our Issue & What Should We Do About It?

(presented by Adam Chapdelaine, Town Manager, to Select Board on July 22, 2019)

Overview

Since 1980 the price of housing in Massachusetts has surged well ahead of other fast growing states including California and New York. While the national “House Price Index” is just below 400, four times what an average house might have cost in 1980, a typical house in Massachusetts is now about 720% what it was in 1980. Median household income in the state has only increased about 15% during the same period. No wonder people in Arlington are feeling the stresses of housing costs if they want to live here and are feeling protective of the equity value time has provided them if they bought years ago.

In response to concerns about zoning, affordable housing and housing density, the Town joined the “Mayors’ (and Managers’) Coalition on Housing” to address these growing pressures. This 12 page slide deck presentation outlines the key data points, the number of low and very low income households in Arlington, the rate of condo conversion that is absorbing rental units, etc.

Solutions are offered including:

• Amendments to Inclusionary Zoning Bylaw

• Housing Creation Along Commercial Corridor – Mixed Use & Zoning Along Corridor

• Accessory Dwelling Units – Potential Age & Family Restrictions

• Other Tools Can Be Considered That Are Outside of Zoning But Have An Impact on Housing

Chapdelaine’s suggested next steps are:

• Continued Public Engagement

• Town Manager & Director of DPCD Meet with ARB

• Select Board & ARB Hold Joint Meeting in Early Fall

• ARB Recommends Strategies to Pursue in Late Fall/Early Winter

The Select Board approved the suggested next steps and a joint ARB/ Select Board meeting should be scheduled in the near future.

Note from Reporter: As a community, Arlington has long prided itself on its economic diversity. With condo conversions, tear downs leading to “McMansions”, higher paid workers arriving in response to new jobs, etc., Arlington is at great risk of losing this diversity that has long enriched the community. Retirees looking to downsize and young people who have grown up in Arlington looking for their first apartment are finding it impossible to stay in town. Shop keepers and town employees are challenged to afford the rising housing costs. With a reconsideration of zoning along Arlington’s transit corridors, Arlington NOW has an opportunity to create new village centers, like those recommended in the recent STATE OF HOUSING report. These village centers along our transit corridors could be higher, denser but also offer the compelling visual design and amenities desired by people who want to walk to cafes, shops and public transit.

by Steve Revilak

The term “AMI” or “Area Median Income” comes up in almost any discussion about affordable housing, because it’s used to set rents and the household incomes for people who are eligible to live in affordable dwellings. AMI is a fairly technocratic concept and my goal is to make the concept (and the numbers) easier to understand.

AMIs are set each year by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; broadly speaking, an AMI is the median income of a region. Arlington is part of the “Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH HUD Metro FMR Area” which consists of more than 100 cities and towns in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Median incomes represent the “middle” family income of an area—half of households make more, and half make less.

In the process of turning median incomes into income limits, HUD also considers household size: larger households are assigned larger AMI limits than smaller ones, in order to reflect the higher cost of living for more family members.

How do these limits translate into affordable housing regulations? Arlington’s affordable housing requirements (aka “inclusionary zoning”) require that rents for affordable units be priced for the 60% area median income, but the dwellings are available to households making up to 70%. Let’s show an example with some numbers.

| Household size | 60% Income Limit | 70% Income Limit | 60% Rent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $68,520 | $79,940 | $1,717/month |

| 2 | $78,360 | $91,420 | $1,959/month |

| 3 | $88,140 | $102,830 | $2,203/month |

HUD considers an apartment suitable for a household if it has one bedroom less than the number of household members, so a two-bedroom apartment would be suitable for a household of three, a one-bedroom would be suitable for a household of two, and a studio would be suitable for a household of one. The monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment would be calculated as follows: $88,140 ÷ 12 × 30% = $2,203. The 30% comes from HUD’s rule that affordable housing tenants should not be cost-burdened, meaning that they pay no more than 30% of their income in rent.$88k or $102k/year can seem like a lot of money (and once upon a time it was). To get a better sense of what these income levels mean, I looked into what kinds of jobs pay these wages. To that end, I found wage information from the Arlington Public Schools report to Town Meeting, the Arlington town budget, and wage data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Here are a few scenarios:

Scenario 1: single adult

Scenario 1 represents a single adult living alone, and earning between $68,520 and $79,940. Jobs in this pay range include:

- Elementary classroom teacher ($62,000 – $75,000)

- Town planner ($75,000 – 79,000)

- Animal Control Officer ($72,000)

- Firefighter ($73,640)

- Librarian ($70,395)

- Lab Technician ($70,710)

- Social Worker ($71,470)

- Subway operator ($72,270)

- Licensed Practical Nurse ($75,690)

- Paralegal ($77,500)

- Chef ($78,040)

- Carpenter ($78,000)

Scenario 2: single parent with household of two

Scenario 2 represents a single parent earning between $78,360 and $91,420/year. Jobs in this pay range include:

- Office Manager – Assessor’s office ($80,399)

- Assistant Town Clerk ($77,375)

- Town Engineer ($74,000 – $80,000)

- Police Department Patrol Officer ($87,000)

- Town Budget Director ($88,488)

- Telecommunications equipment installer ($80,350)

- Plasterer and Stucco Mason ($82,250)

- Electrician ($82,380)

- Cement Mason ($86,250)

- Plumber and pipe fitter ($90,580)

Scenario 3: household of two, both adults

Scenario 3 has two adults, each earning $39,180 – $45,710 per year. Jobs in this salary range include several that we’ve come to know as “essential workers” during the pandemic.

- Special education teaching assistant ($34,290)

- Arlington Public Schools Paraprofessional ($36,290 – 42,440)

- Substitute Teacher ($34,921)

- Inspectional Services Record Keeper ($44,481)

- Food preparation worker ($39,590)

- Bartender ($39,730)

- Childcare worker ($40,470)

- Ambulance Driver ($40,890)

- Waiter ($41,440)

- Pharmacy aide ($41,460)

- Bank teller ($42,270)

- Tailor and dressmaker ($43,790)

- Restaurant cook ($44,140)

You may have noticed gaps in these lists — for example, there are no jobs listed in the $50,000 – $60,000 range because it’s in between the income limits for one- and two-income households. It’s also worth noting that a fair number of town employees’ salaries would qualify them for affordable housing (the town is Arlington’s largest employer).

So who qualifies to live in affordable housing? People with a lot of ordinary, working-class jobs, including many town employees.