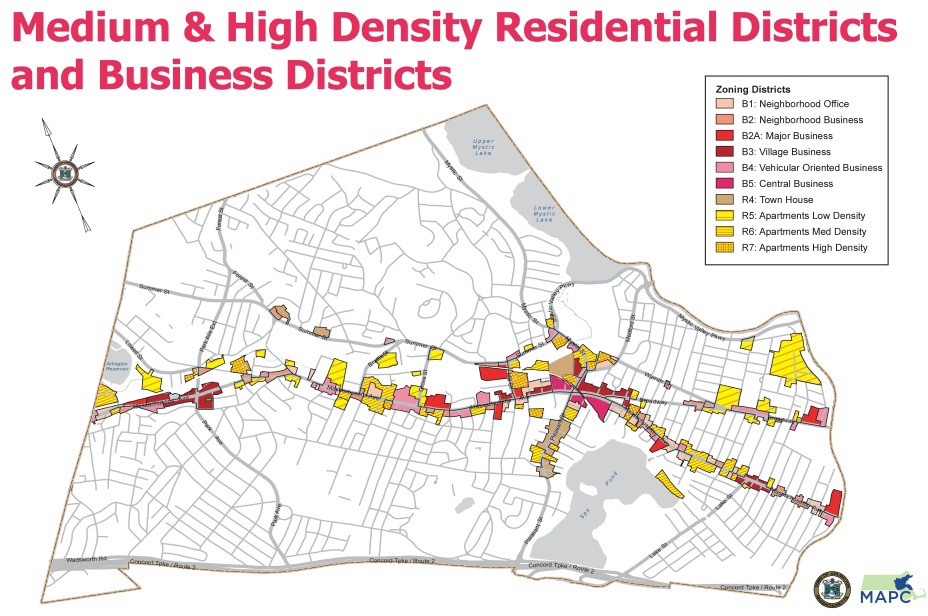

The discussions on zoning have been confusing because while zoning covers ALL of Arlington’s land and the zoning bylaws for all Arlington’s zones are referenced, the key issues of greatest interest to Town Meeting are the discussions about increasing density. These discussions pertain ONLY to those properties currently zoned as R4-R7 and the B (Business) districts. These density related changes would affect only about 7% of Arlington’s land area. The map shows the specific zones that would potentially be affected. They lay along major transportation corridors.