Related articles

The City of Somerville estimates that a 2% real estate transfer fee — with 1% paid by sellers and 1% paid by buyers, and that exempts owner-occupants (defined as persons residing in the property for at least two years) — could generate up to $6 million per year for affordable housing. The hotter the market, and the greater the number of property transactions, the more such a fee would generate.

Other municipalities are also looking at this legislation but need “home rule” permission, one municipality at a time, from the state to enact it locally. Or, alternatively, legislation could be passed at the state level to allow all municipalities to opt into such a program and design their own terms. This would be much like the well regarded Community Preservation Act (CPA) program that provides funds for local governments to do historic preservation, conservation, etc.

This memorandum from the City of Somerville to the legislature provides a great deal of information on the history, background and justification for such legislation.

House bill 1769, filed January, 2019, is an “Act supporting affordable housing with a local option for a fee to be applied to certain real estate transactions“.

COMMENT:

KK: This article suggests Arlington may be likely to pass a real estate transfer tax: https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/12/19/boston-one-step-closer-to-a-luxury-real-estate-transfer-tax/

During the last few months, Arlington’s Department of Planning and Community Development and Zoning Bylaw Working Group have been conducting a study of the town’s industrial districts. The general idea has been to begin with an assessment of current conditions, and consider whether there are zoning changes that might make these districts more beneficial to the community as a whole.

To date, the major work products of this effort have been:

- A study of existing conditions, market analysis, and fiscal impact. Among other things, this slide deck will show you exactly where Arlington’s industrial districts are located.

- A set of test build scenarios.

- An initial set of zoning recommendations. These are high level ideas; they’d need further refinement to fit into the context of our zoning bylaws.

- A survey, to gather public input on several of the high-level recommendations.

The survey recently closed. I asked the planning department for a copy of they survey data, which they were generous enough to provide. That data is the subject of this blog post.

The survey generally consisted of pairs of questions: a yes/no or multiple choice, coupled with space for free-form comments. I’ll provide the yes/no and multiple choice questions (and answers!) here. Those interested in free-form commentary can find that in the spreadsheet linked at the bottom of this article.

208 people responded to the survey.

Industrial Zoning questions

(1) Which of the following uses would you support in the Industrial Districts? (check all that apply) (208 respondents)

| Industrial | 62.02% |

| Office | 76.92% |

| Breweries, Distilleries, and Wineries | 86.06% |

| Mixed Use (Office and Industrial Only) | 67.31% |

| Food Production Facilities | 55.77% |

| Flexible Office/Industrial Buildings | 68.27% |

| Coworking Space | 68.75% |

| Maker Space | 63.46% |

| Vertical Farming | 65.38% |

| Work Only Artist Studio | 63.94% |

| Residential | 42.79% |

| Other (please specify) | 12.02% |

(2) Would you support a waiver of the current 39-foot height maximum to allow heights up to 52 feet if the Applicant had to meet other site design, parking, or environmental standards? (207 respondents)

| Yes | 74.40% |

| No | 22.22% |

(3) Would you support a small reduction in the amount of required parking by development as an incentive to provide more bike parking given the districts’ proximity to the Minuteman Bikeway? (208 respondents)

| Yes | 68.27% |

| No | 30.77% |

(4) Would you support a variable front setback of no less than 6 feet and no more than 10 feet to bring buildings closer to the sidewalk and create a more active pedestrian environment? (207 respondents)

| Yes | 66.18% |

| No | 28.50% |

(5) Would you support zoning changes that require new buildings in the district to have more windows and greater building transparency, as well as more pedestrian amenities such as lighting, landscaping, art, or seating? (207 respondents)

| Yes | 81.64% |

| No | 13.53% |

Demographic questions

(7) Do you….(check all that apply) (206 respondents)

| live in Arlington | 99.51% |

| work in Arlington | 23.79% |

| own a business in Arlington | 9.71% |

| work at a business in one of Arlington’s industrial districts | 1.46% |

| own a business in one of Arlington’s industrial districts | 1.46% |

| patron of Arlington retail and restaurants | 76.70% |

| elected official in Arlington | 6.80% |

(8) What neighborhood do you live in? (207 respondents)

| Arlington Heights | 30.43% |

| Little Scotland | 2.42% |

| Poet’s Corner | 0.97% |

| Robbins Farm | 5.80% |

| Turkey Hill/ Mount Gilboa | 11.11% |

| Morningside | 4.35% |

| Arlington Center | 10.14% |

| Jason Heights | 8.21% |

| East Arlington | 20.77% |

| Kelwyn Manor | 0.00% |

| Not Applicable | 0.48% |

(9) How long have you lived in Arlington? (207 respondents)

| Under 5 years | 19.32% |

| 5 to 10 years | 15.46% |

| 10 to 20 years | 19.81% |

| Over 20 years | 45.41% |

According to US Census data [1], 72% of Arlington’s residents moved to Arlington since the beginning of the 2000’s (i.e., 20 years ago or less). The largest group responding to this survey has lived here 20+ years, implying that the results may be more reflective of long-term residents opinions.

(10) Please select your age group (199 respondents)

| Under 18 | 0.00% |

| 18-25 | 1.01% |

| 26-35 | 13.57% |

| 36-45 | 22.11% |

| 46-55 | 25.13% |

| 56-65 | 20.60% |

| 66-80 | 16.58% |

| 80+ | 1.01% |

(11) What is your annual household income? (188 respondents)

| $0-$19,999 | 1.06% |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 1.60% |

| $40,000-$59,999 | 5.32% |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 9.04% |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 4.79% |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 23.94% |

| $150,000-$200,000 | 17.55% |

| More than $200,000 | 36.70% |

Full Survey Results

As noted earlier, the survey provided ample opportunity for free-form comments, which are included in the spreadsheet below. There were a number of really thoughtful ideas, so these are worth a look.

Arlington Industrial District Survey

Footnotes

[1] https://censusreporter.org/profiles/16000US2501640-arlington-ma/, retrieved August 10th, 2020

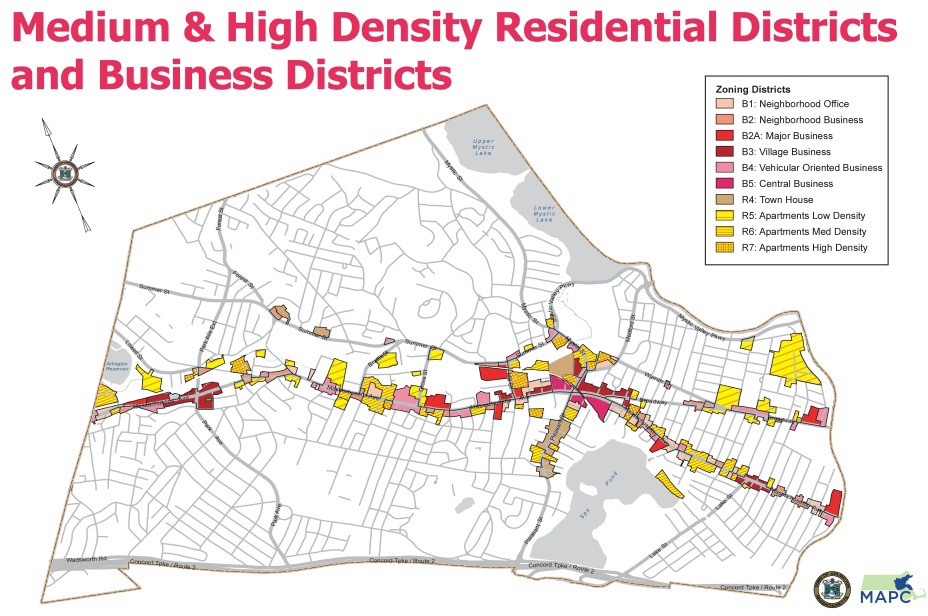

The discussions on zoning have been confusing because while zoning covers ALL of Arlington’s land and the zoning bylaws for all Arlington’s zones are referenced, the key issues of greatest interest to Town Meeting are the discussions about increasing density. These discussions pertain ONLY to those properties currently zoned as R4-R7 and the B (Business) districts. These density related changes would affect only about 7% of Arlington’s land area. The map shows the specific zones that would potentially be affected. They lay along major transportation corridors.

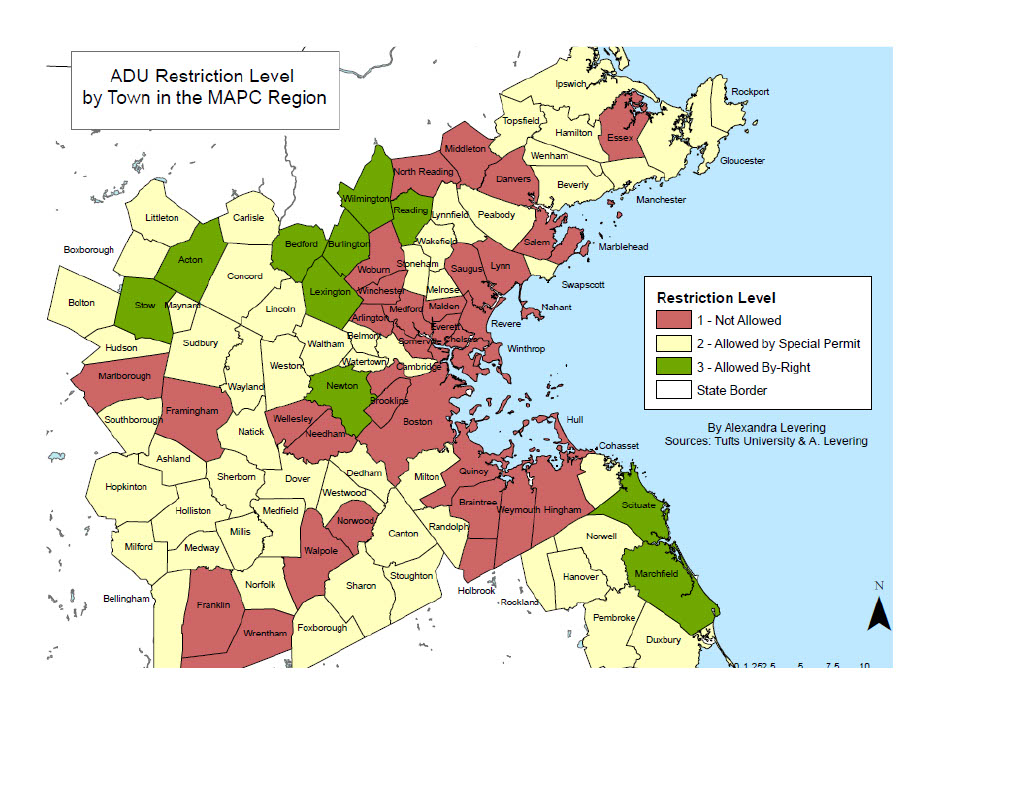

by Amy Dain, for Pioneer Institute of Public Policy Research and Smart Growth Alliance, July 2018 (This study updates a 2004-06 study on ADUs by the Pioneer Institute.)

Even in the midst of a housing crisis, zoning laws prohibit most homeowners in cities and towns around Boston from adding accessory dwelling units (ADUs) to their single family houses. An ADU is an apartment within or behind an own- er-occupied single family house that appears from the street to be a single-family as opposed to a two-family house.

Homeowner-voters can be reassured that new rental hous- ing that could be added as ADUs would be highly dispersed and barely visible. The houses are owner-occupied; the land- lord lives next to the ADU renters, so the risk of property-ne- glect or loud parties is minimal. The houses also have to look like single family houses. Since household sizes are shrinking, new residents in ADUs might maintain current neighborhood population densities, but are unlikely to increase them.

Moreover, ADUs are permitted at such low levels now — only 2.5 permits annually per municipality where they are allowed — that permitting levels could increase substantially without being at all noticeable in neighborhoods. If the region were to average five permits per municipality per year across 100 municipalities, over a decade, ADUs could provide 5,000 apartments, dispersed among 538,000 single family houses. Less than one in 100 houses would have an ADU, yet the new rentals would house thousands of people.

Click HERE for the full report.

(published June, 2019)

Overview

To solve the extraordinarily large deficit in housing for the greater Boston region, over 180,000 units of new housing should come on line in the next few years. This deficit is the result of a rapid expansion in in-migration due to new job creation, with no commensurate increase in housing production for the people taking those new jobs.

The report concludes that zoning is a primary culprit in restricting the development of an adequate housing supply, creating a “PAPER WALL” keeping out newcomers. The cost of this inadequate supply is a huge demand for housing which, in turn, bids up the price for available housing. The following “culprits” are considered: inadequate land area zoned for multi-family housing; low density zoning; age restrictions and bedroom restrictions; excessive parking requirements; mixed use requirements and approval processes. Alternative zoning models are suggested.

Elements such as “Approval Process”, “Mixed Use”, “Village Centers vs Isolated Parcels” and “Building Up or Building Out” are considered.

Researcher Amy Dain reports on two years of research into the regulations, plans and permits in the 100 cities and towns surrounding Boston. The research was commissioned by the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance and funded collaboratively with: Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association, Home Builders & Remodelers Association of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Association of Realtors, Massachusetts Housing Partnership, MassHousing, and Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

For the full report see: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/03/FINAL_Multi-Family_Housing_Report.pdf

For a power point slide presentation see: https://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/04/DainZoningMFPresentationShare2019.pdf

For the Executive Summary see: https://equitable-arlington.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/June-2019-Multi-Family-Housing-Report_Executive-Summary.pdf

from Alexandra P. Levering , Thesis, Urban & Environmental Policy and Planning, Tufts University, August 2017

By 2017 65 out of 101 municipalities in the greater Boston (MAPC) region allowed Accessory Dwelling Units by right or by special permit. The average number of ADU’s added per year was about 3. But by 2017, Lexington had 75 ADUs, Newton had 73 and Ipswich had 66. It is a slow process for a variety of reasons, but the number of units grows over time.

AARP recommends ADU’s. The help homeonwers cover rising housing costs by providing income trhough rent. They also create a space for a caretaker or a family member to live close by, as the homeowner ages.

Autism Housing Pathways and Advocates for Autism of MA (AFAM) came together to advocate for an ADU bylaw to benefit parents of adult children with disabilities. For more information see her complete thesis (with a very useful set of tables and bibliography) HERE.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) provide multigenerational housing options for aging parents and for adult children. They help families manage changing lifestyle, fiscal and/or caretaking situations.

This type of housing is seen by many as a clear opportunity to offer more affordable residential opportunities. One reason why they are slow to develop is the cost of renovation and construction for homeowners. Some communities offer low or no interest loans to encourage more ADU development.

WE HAVE WINNERS!

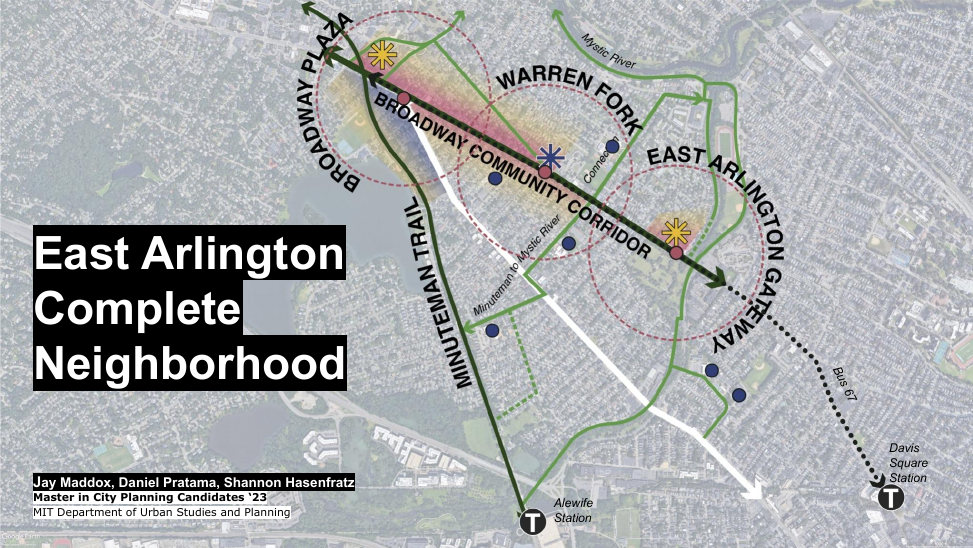

MIT Dept. of Urban Studies and Planning

Jay Maddox maddoxja@mit.edu; Shannon Hasenfratz shasenfr@mit.edu; Daniel Pratama danielcp@mit.edu

Title: EAST ARLINGTON COMPLETE NEIGHBORHOOD

Arlington High School CADD Program

Petru Sofio psofio2024@spyponders.com; Talia Askenazi taskenazi2025@spyponders.com

Title: ENVISION BROADWAY

Winslow Architects

John Winslow john@winslowarchitects.com; Phil Reville philip@winslowarchitects.com; Dolapo Beckley dolapo@winslowarchitects.com

Title: REDEFINING THE BROADWAY CORRIDOR: A 2040+ VISION

Contest Personnel

- Judges: Adria Arch, artist; Caroline Murray, construction project manager; Rachel Zsembery, architect

- Organizer: Barbara Thornton

- Host: Lenard Diggins, Chair, Arlington Select Board

- Sponsor: Civic Engagement Group, Envision Arlington, Town of Arlington MA

- Producer: ACMI

Special thanks

- ACMI production team: Katie Chang, James Milan, Jeff Munro, Jason Audette, Anim Osmani, Jared Sweet, Michael Armanious

- Civic Engagement Group (CEG): Greg Christiana, Len Diggins

- Jenny Raitt- Arlington DHCD Director, for laying the groundwork with the 2019 Broadway Corridor Study

- Jeffrey Levine, MIT DUSP faculty, led the original 2019 Broadway Corridor study team

- Kambiz Vatan & Cinzia Mangano, AHS CADD faculty and community volunteer

- Jane Howard, whose volunteer efforts over many years made possible Vision 2020 and Envision Arlington, leading to CEG and thus making this project possible by giving our town of Arlington the infrastructure, the “DNA”, to make this kind of civic engagement happen.

Background

The Civic Engagement Group (CEG), part of the Town of Arlington’s Envision Arlington network of organizations, is sponsoring the Broadway Corridor Design Competition. Architects, planners, designers and artists from around the region are encouraged to register by April 8, 2022.

This as an opportunity for designers and architects in the region to have some fun exercising real creativity to leapfrog into the post pandemic future and create a 2040+ VISION of what the built environment of a specific neighborhood (our Broadway Corridor area) might look like.

Although the cash prize is small, the pay off will be bragging rights, recognition and a possible opportunity to help shape the upcoming Arlington master plan revision process.

The information: flyer

The plan: Design Competition launch plan

The background data: 2019 Broadway Corridor Study

Register to enter: Sign up information

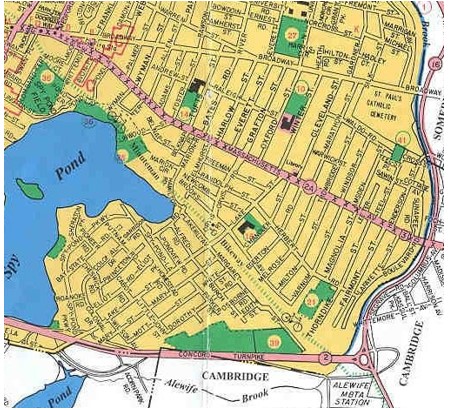

Broadway St. is a major bus route and transit corridor through Arlington to Cambridge. It is close enough to the Alewife MBTA Station to possibly be, at least partially, included in the planning for Arlington’s “transit area” status under the state Dept. of Housing and Community Development’s new guidelines.

by Alexander vonHoffman, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, February 2006

The case study shows that in the 1970s the Town of Arlington completely abandoned its policy of encouraging development of apartment buildings—and high-rise buildings at that—and adopted requirements that severely constricted the possibilities for developing multifamily dwellings. Although members of the elite introduced the new approach, they were backed by rank-and-file citizens, who took up the cause to protect their neighborhoods from perceived threats.

The report outlines an intentional effort using land use and planning tools like zoning and building approvals, to exclude those with less desirable income or racial characteristics from residing in Arlington. Additional perspectives on Arlington’s exclusionary zoning efforts during this period are reported here.