The new proposal is just the most recent step in a process that reaches back almost a decade, culminating in the Master Plan (2015), the Housing Production Plan (2016) and the mixed-using zoning amendments of 2016. The Town has consistently proposed smart growth: more development along Arlington’s transit corridors to increase the tax base, stimulate local commerce, and provide more varied housing opportunities for everyone, including low and moderate income Arlingtonians. This year’s proposals are no head-long rush into change. Today’s debate is similar to the debate before Town Meeting three years ago. If anything, progress has been frustratingly slow. To realize the Master Plan’s vision of a vibrant Arlington with diverse housing types for a diverse population, we must stay the course on which we have been embarked for so long.

Related articles

Interview with Aaron Clausen, AICP; City of Beverly, Director, Planning and Community Development

Rather than express generalized worry about the “lack of affordable housing”, Peabody, Salem and Beverly have created an intermunicipal Memorandum of Mnderstanding (MOU) to very specifically define and target the problem and the population they want to address.

According to Aaron Clausen, “There is a fair amount of context that goes along with the MOU, but primarily the communities got together as sort of a coalition to survey and understand what was going on relative to homelessness. What came out of that is a recognition that there is not enough affordable housing generally, and particularly transitional housing, or more specifically permanent supportive housing.

“Salem and Beverly both have shelters, however the shelters were basically serving as permanent housing (and running out of space). That won’t help someone into a stable housing situation. Anyway, this was the agreement (attached MOU) and the good news is that it has resulted in affordable housing projects; one is done in Salem for individuals and Beverly has a 75 unit family housing project permitted and seeking funding that has a set aside for families either homeless or in danger of becoming homeless.

“There is also a redevelopment of a YMCA in downtown Beverly that will increase the number of Single Room Occupancy units. I wouldn’t say that the MOU got it done by itself but it helps demonstrate a regional approach. ”

To see the actual Memorandum of Understanding between these three municipalities to address affordable housing, particularly for people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, click HERE.

by JP Lewicke

When you love the place you live and you want to help it become even better, how can you make a difference? Arlington is an extremely civically active community, with hundreds of residents involved in Town Meeting, several dozen boards and committees, and numerous other groups that play an important role in improving our town. The vast array of options can be a bit dizzying for a newcomer to sort through.

Fortunately, Arlington has recently launched Arlington Civic Academy to provide interested residents with a pathway to becoming more civically literate and involved. Ably organized by Joan Roman, Arlington’s Public Information Officer, Civic Academy takes place over the course of six weeks and aims to provide participants with the information they need for constructive civic engagement. Applications are open from now until August 4th for the fall session, which will take place between September 12th and October 17th.

Find Out How the Town Works

It’s clear that town government takes the Academy seriously. The Town Manager, Select Board Chair, Town Moderator, and the heads of several town departments have stayed late into the evening to attend Civic Academy sessions. Their formal presentations do a great job of explaining how different areas of town government work and how best to get involved, but the chance to meet them and ask them questions is equally valuable. The participants usually have a lot of very insightful questions, and it’s a great opportunity to learn more and become a more effective advocate in the future.

Participants Make Arlington Civic Academy Great

The other participants are another great part of the program. It’s also a great chance to make connections with other people who are equally enthusiastic about learning and getting involved in making their town a better place. There have been two sessions of the program so far, and several participants have gone on to run for Town Meeting, join the Master Plan Update Advisory Committee, volunteer for last fall’s tax override campaign, and propose warrant articles. We just had a get-together for members of both Civic Academy sessions to meet each other and network, and are hopeful that Civic Academy alumni can help connect future participants in the program to opportunities to get involved in helping Arlington become even better.

Helping Others Learn to Navigate Town Processes

I ran for Town Meeting this spring after attending Civic Academy last fall, and I found that it served me well after I was elected. It taught me how the budgeting process worked, including all the steps from the Town Manager’s office working with individual departments, the Finance Committee compiling a cohesive budget, and Town Meeting approving that budget. When constituents from my precinct have questions about how to get help with something from the town, I know which boards or committees or town departments they should reach out to. I also have a better understanding of the current constraints and opportunities faced by our town across multiple areas.

When I started working with Paul Schlictman on advocating for extending the Red Line further into Arlington, I reached out to the members of my Civic Academy class to see if they were also interested, and several of them were incredibly generous with their time and helped us set up our website and mailing list. I would highly recommend applying to Civic Academy, and I’m very thankful that the town puts so much effort into making it a great experience.

State Senator Cindy F. Friedman has written a letter to Town Meeting Members supporting Warrant Article 12 and a meaningful MBTA Communities Plan. She writes:

We all want Arlington and Massachusetts to remain welcoming, accessible places to live. In addition to our deficit of housing, I recognize the importance of encouraging smaller, more sustainable housing in walkable areas. Arlington’s Warrant Article 12 will provide a meaningful framework for making progress in these areas. The problems we are experiencing now —out of reach housing prices for new construction and existing homes — exacerbate the crisis and are seriously threatening the economic vibrancy of our communities.

To read Friedman’s full letter, click here for the PDF.

This timely report on the question of affordable housing vs. density comes from the California Dept. of Housing & Community Development and mirrors the situation in the region surrounding Arlington MA.

Housing production has not kept up with job and household growth. The location and type of new housing does not meet the needs of many new house- holds. As a result, only one in five households can afford a typical home, overcrowding doubled in the 1990’s, and too many households pay more than they can afford for their housing.

Myth #1

High-density housing is affordable housing; affordable

housing is high-density housing.

Fact #1

Not all high density housing is affordable to low-income families.

Myth #2

High-density and affordable housing will cause too much traffic.

Fact #2

People who live in affordable housing own fewer cars and

drive less.

Myth #3

High-density development strains public services and

infrastructure.

Fact #3

Compact development offers greater efficiency in use of

public services and infrastructure.

Myth #4

People who live in high-density and affordable housing

won’t fit into my neighborhood.

Fact #4

People who need affordable housing already live and work

in your community.

Myth #5

Affordable housing reduces property values.

Fact #5

No study in California has ever shown that affordable

housing developments reduce property values.

Myth #6

Residents of affordable housing move too often to be stable

community members.

Fact #6

When rents are guaranteed to remain stable, tenants

move less often.

Myth #7

High-density and affordable housing undermine community

character.

Fact #7

New affordable and high-density housing can always be

designed to fit into existing communities.

Myth #8

High-density and affordable housing increase crime.

Fact #8

The design and use of public spaces has a far more

significant affect on crime than density or income levels.

See an example of a “case study” of two affordable housing developments in Irvine CA, San Marcos at 64 units per acre.

San Paulo at 25 units per acre.

Both are designed to blend with nearby homes.

Beginning last July, 2020, the Town of Arlington and community groups in the town are sponsoring a number of webinars and zoom conversations addressing the need for affordable housing programs in Arlington. Several factors contribute to the Arlington housing situation: diversity of housing types, prices, diversity of incomes, availability of housing subsidies, rapid growth in property values that greatly exceed the rate of growth of income.

But racism, both historic and current, continues to stand out as a significant force contributing to the difficult housing situation.

One of the first public discussion in the Town on this subject was organized by Arlington Human Rights Commission (AHRC) on July 8, 2020. View it here:

(By Vince Baudoin and James Fleming)

Could Arlington be better using its curb space? Here are some ways the curb can be used to create green infrastructure, promote public safety and accessibility, support sustainable transportation, strengthen business districts, and enable new ‘car-light’ development.

Roughly six inches high and made of concrete or granite, the curb marks the edge of the roadway, channels runoff, protects the sidewalk, and gathers stray leaves. When not assigned any other use, the space in front of the curb it usually serves as free storage for personal automobiles.

Yet the humble curb is a limited resource that can serve the community in many more ways. Have you thought about how your town budgets its curb space? For that matter, has your town thought about how it budgets its curb space?

While Arlington mostly uses its curb space for parking, some areas have other curb uses designed to achieve a specific goal. Consider the streets you use often. Have you seen an unsolved problem, or a missed opportunity, that a different use of the curb could help solve?

Create green infrastructure

The Town has miles of paved roadway. When it rains or snows, water runs into storm drains, carrying salt, oil, and other pollutants with it. The storm drains dump these pollutants directly into long-degraded waterways such as the Mill Brook, Alewife Brook, and the Mystic River. The Public Works department struggles to keep grates clear and drains from overflowing.

One solution: Use the curb for more greenery! The curb can be extended to create a rain garden or tree planting strip. The rain garden helps slow runoff and filter the water before it enters the drain, while trees benefit from additional room for the roots to grow without damaging the sidewalk. A side benefit: narrowing the street encourages drivers to slow down, making neighborhoods safer.

Promote public safety and accessibility

Often, portions of the curb are set aside for public safety purposes. For example, a fire lane provides fire department access to key buildings, such as the high school, shown below. Fire hydrants also enjoy special curb status.

Other times, no-parking zones are established to enhance the free flow of traffic, such as here at Broadway Plaza:

Where pedestrian crosswalks are present, a curb extension is a key safety enhancement. By narrowing the roadway, the curb extension encourages drivers to slow down and look for pedestrians. For pedestrians, it reduces the distance they must cross and prevents cars from parking directly next to the crosswalk and blocking visibility.

Finally, accessible parking spaces can be created along the curb. Arlington has at least 50 designated permit-only on-street parking spaces that provide convenient parking for residents with mobility issues or other disabilities.

Support sustainable transportation

When the curb is mostly used for cars, it is easy to overlook how curbside facilities can enhance other forms of transportation.

In the space of one or two parked cars, this bikeshare station offers space for 11 bikes. However, because it is installed on the roadway, it must be removed every winter so that snow can be cleared. If the curb were extended, the bikeshare station could be used year-round. Another nice feature is bicycle parking: the space to park one car can be used to park six or more bicycles.

A bus stop allows buses to pull to the curb. In some cases, it is appropriate to extend the curb so the bus would stop in the traffic lane; otherwise, it may experience delays when it merges back into traffic.

A bus priority lane provides a dedicated right of way for buses, helping to improve on-time performance. To date, these lanes extend only a few hundred feet into Arlington along Mass Ave. They have proven beneficial in many other communities.

Bike lanes, particularly if they are separated from cars by a physical buffer, greatly enhance the safety and comfort of people traveling on two wheels.

But with a limited roadway width, adding bike lanes is difficult unless the community is flexible enough to consider consolidating curb parking on one side of the street, or moving it to side streets entirely.

Finally, the Town could expand the use of on-street spaces for electric vehicle charging stations, such as this one on Park Ave:

Strengthen business districts

Nowhere is the curb more valuable than in business districts. Businesses thrive when their customers have a convenient way to reach them. Metered parking encourages people to park, do their business, and move along so another patron can take that space. Revenue from parking meters can be spent to improve the business district–for example, by planting flowers and trees.

Metered parking is not the only valuable use of curb space in a business district. Outdoor dining is a way the Town can directly support its restaurants by enabling them to serve additional customers. Here is one example in Arlington Center:

And in Arlington Heights:

Other valuable curb uses in business districts include taxi stands and loading zones. Loading zones in particular are crucial to businesses’ success and help prevent the street from being clogged by early-morning delivery trucks, late-night food-delivery vehicles, and everything in between.

Enable new ‘car-light’ development

With high housing costs and a relatively small commercial tax base, Arlington could benefit from some kinds of development. However, land is valuable and lots are small, so if new buildings are required to have large parking lots, it is very difficult to build new homes and businesses. Plus, large parking lots bring more cars and more traffic. But better curb management can help resolve this dilemma, supporting car-light development that is more sustainable and affordable.

For example, on-street permit parking can enable nearby development with few or no off-street parking spaces. New housing or businesses are a better use of land than parking and will generate more property tax revenue. When parking permits are priced appropriately, they are available to residents who need them but discourage households from adding extra cars they do not need.

Take these hillside houses: access to on-street parking made it possible to build on a steep hillside, where it would have been too expensive and difficult to blast to create off-street parking.

Conclusion

Ask your town leaders if they have a curb management strategy. Is the Town using its limited curb space in support of goals such as green infrastructure, public safety and accessibility, public transportation, local business, and car-light development?

A municipality’s master plan is intended to set the vision and start the process of crafting the future of the municipality in regard to several elements, housing, history, culture, open space, transportation, finance, etc. Arlington began a very public discussion about these issues and the development of the Master Plan in 2012. In 2015, after thorough community wide discussion, the Master Plan was adopted by Town Meeting. This year, 2019, the focus is on passing Articles that will amend the current zoning bylaws in order to implement the housing vision that was approved in 2015.

It’s New Year’s eve and I’m determined to get my third and final “Arlington 2020” article written and posted before 2021 rolls in. I’ve written these articles to paint a picture of Arlington’s housing stock, and how our housing costs have changed over time. The first article looked at the number of one-, two-, and three-family homes and condominiums in Arlington. The second article looked at how the costs of these homes has varied over time.

In this article, I’m going to look at the per-unit costs for our different housing types. The per-unit cost is just the assessed value, divided by the number of units. For condos and single-family homes, the unit cost is simply the assessed value. For two-family homes, it’s the assessed value divided by two. For a ten-unit apartment building, it’s the assessed value divided by ten. We’ll look at the price ranges within housing types, as well as the general differences between them.

The information here doesn’t include residential units from Arlington’s 76 mixed-use buildings. (My copy of the assessor’s data doesn’t distinguish between residential and commercial units in these buildings; I’ll try to say more about them in 2021.) It also omits units owned by the Arlington Housing Authority.

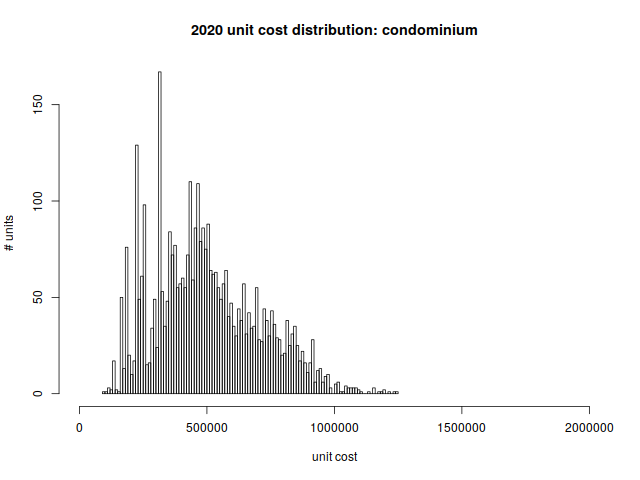

Condominiums

Condominiums provide the most variety and cost diversity. A condo can be half of a duplex, or part of a much larger multi-family building. The low end of the scale tends to be 500–600 square foot units that were built in the 1960’s; the high end tends to be more spacious new construction.

This graph is a histogram, as are the others in this article. The horizontal axis shows cost per unit, and the vertical axis shows the number of units in each particular cost band.

The per-unit price distribution is

| min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $92,600 | $344,450 | $473,100 | $500,086 | $640,850 | $1,241,000 |

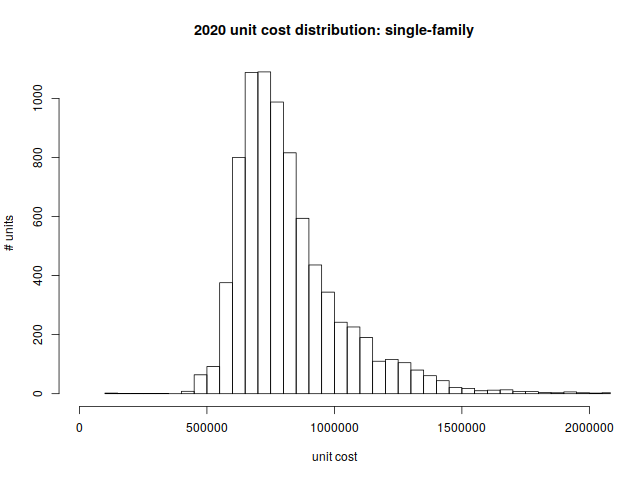

Single-family homes

Single family homes are heavily concentrated around the $700,000 mark. There’s very little available for less than a half million dollars.

Per unit rice distribution:

| min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $103,700 | $679,900 | $771,900 | $825,172 | $908,750 | $3,232,700 |

The $103,700 single-family home deserves some explanation. The property straddles the border between Arlington and Lexington; it appears that the $103k assessed value reflects the portion that lies in Arlington.

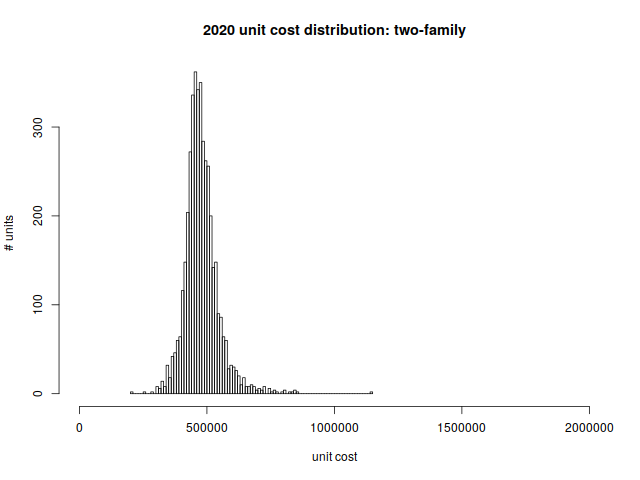

Two-family Homes

Two-family homes are the bread and butter of East Arlington; they’re also common in the blocks off Mass ave near Brattle Square and the heights. Many of these homes are older and non-conforming, and they’re gradually being renovated and turned into condominiums.

As a reminder, these are costs per unit (as opposed to the cost of the entire two-family home).

Per unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $209,050 | $440,550 | $472,000 | $479,175 | $508,588 | $1,140,450 |

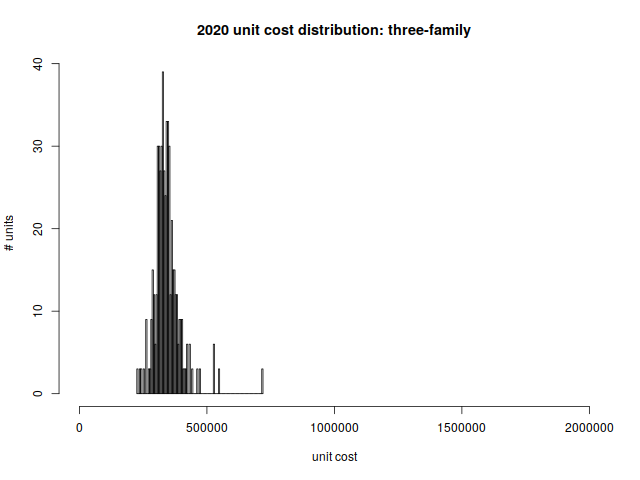

Three-family Homes

Unlike Dorchester and Somerville, three-family homes are not a staple of Arlington’s housing stock. But we have a few of them. Most were built between 1906 and 1930.

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $227,567 | $313,733 | $336,950 | $344,292 | $362,600 | $719,000 |

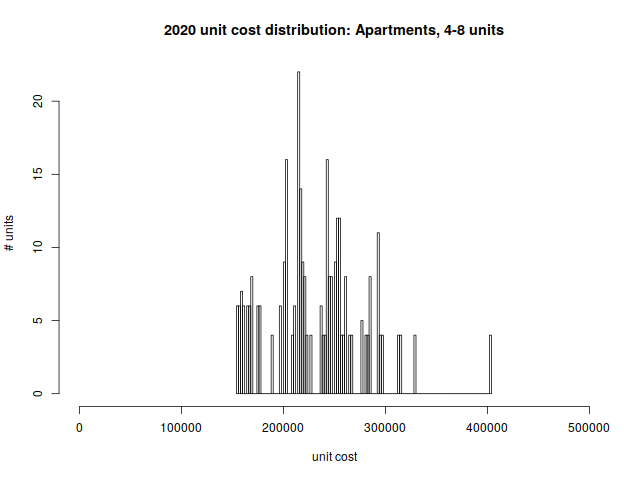

Small Apartments (4–8 units)

The majority of Arlington’s small apartment buildings were constructed during the first half of the 20th century. The most recent one dates from 1976.

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $154,950 | $202,950 | $227,775 | $231,619 | $255,775 | $403,875 |

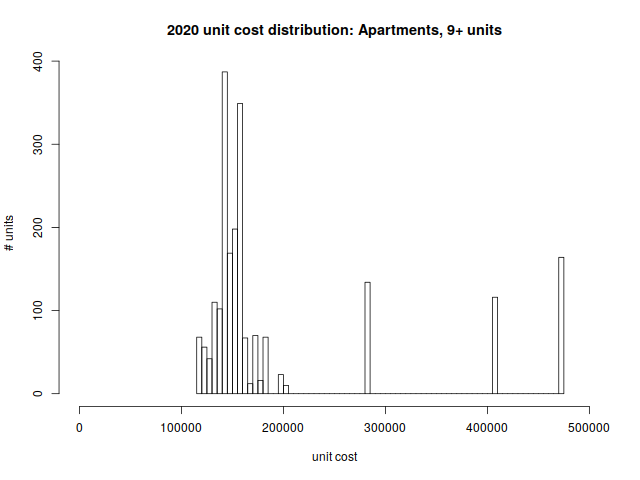

Large Apartments (9+ units)

You’ll see three outliers in the per unit-cost distribution for large apartment buildings. These correspond to the newest apartment complexes in Arlington: The Legacy (2000), Brigham Square (2012), and Arlington 360 (2013).

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $117,013 | $141,383 | $153,006 | $195,789 | $170,973 | $474,631 |

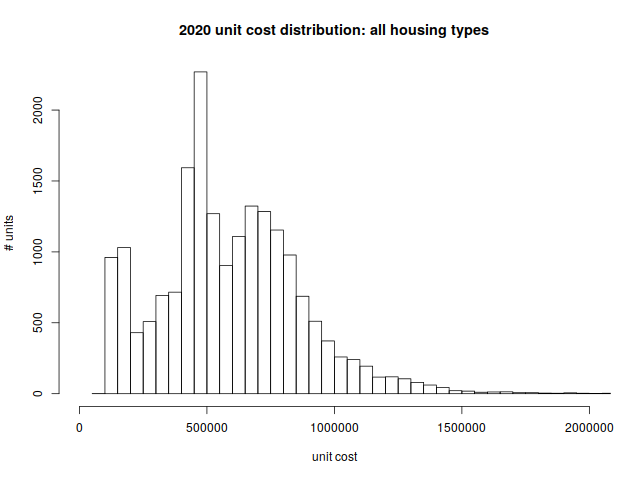

All combined

Finally, we’ll put it all together in one picture, representing nineteen-thousand and some odd homes in town.

Per-unit price distribution:

| Min | 1st quartile | median | mean | 3rd quartile | max |

| $92,600 | $417,175 | $555,825 | $587,975 | $759,900 | $3,232,700 |

While there are lower-priced options available, a person coming to Arlington should expect to buy (or rent) a property that costs just shy of half a million dollars (or more).

Here is a spreadsheet with the cost distributions mentioned in this article.