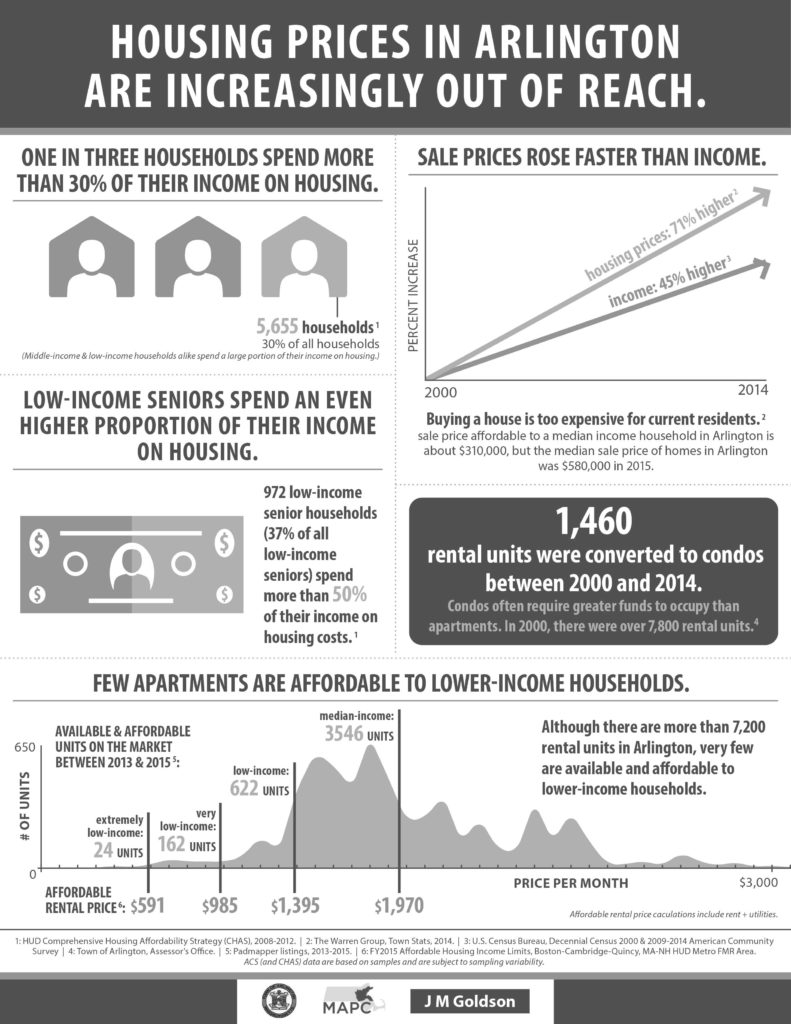

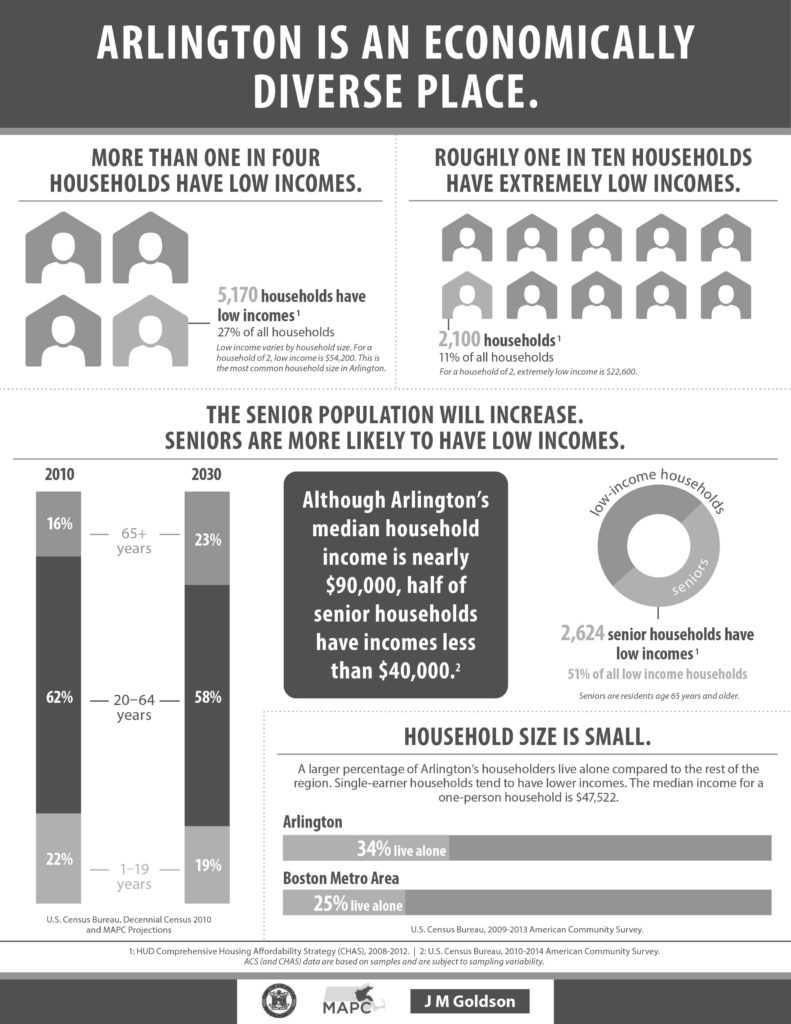

In 2015 Town Meeting approved the Master Plan. Following is the Housing chapter of that plan. It contains a great deal of information about details of the housing situation in Arlington, challenges of housing price increases, needs for specialty housing, opportunities for meeting these needs, etc. The authors found that “most cities and towns around Arlington experienced a significant rise in housing values from 2000 to 2010. A 40 percent increase in the median value was fairly common. However, Arlington experienced more dramatic growth in housing values than any community in the immediate area, except Somerville. In fact, Arlington’s home values almost doubled.” This and related data helps explain why the need for affordable housing is now so acute.

Related articles

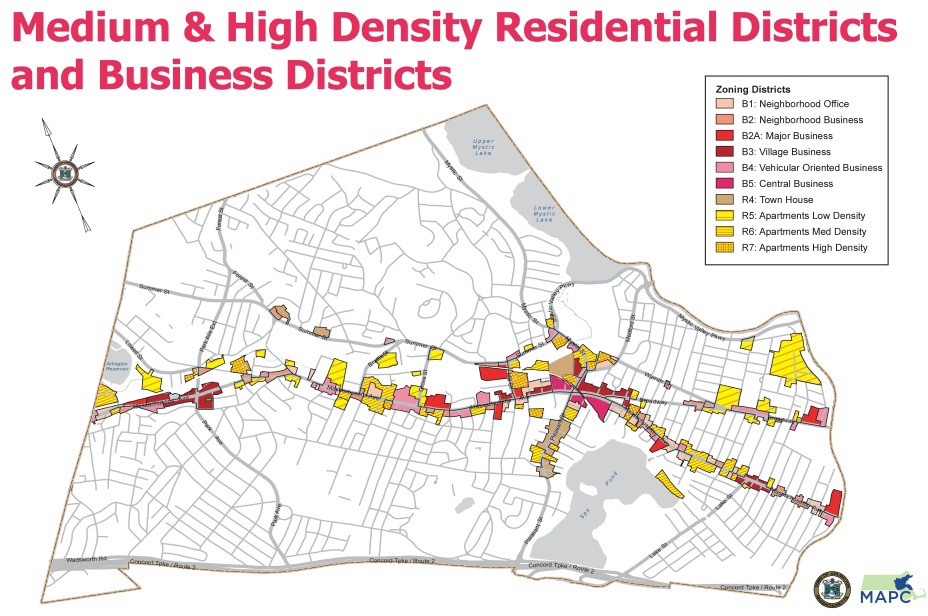

The discussions on zoning have been confusing because while zoning covers ALL of Arlington’s land and the zoning bylaws for all Arlington’s zones are referenced, the key issues of greatest interest to Town Meeting are the discussions about increasing density. These discussions pertain ONLY to those properties currently zoned as R4-R7 and the B (Business) districts. These density related changes would affect only about 7% of Arlington’s land area. The map shows the specific zones that would potentially be affected. They lay along major transportation corridors.

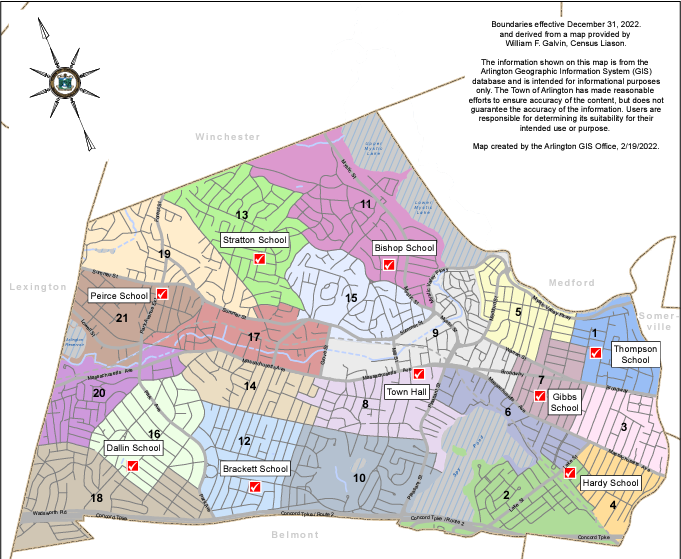

You may not know who your Town Meeting Members are. You may not even know what precinct you live in. We’re here to help!

What’s My Precinct?

This PDF map of Arlington is divided by precinct. You may need to zoom in to see your precinct.

Who Are My Town Meeting Members?

The town of Arlington has a public list of town meeting members and their contact information. Send them an email telling them how you feel, or ask them if you can take a walk and discuss the MBTA Communities Plan.

State Senator Cindy F. Friedman has written a letter to Town Meeting Members supporting Warrant Article 12 and a meaningful MBTA Communities Plan. She writes:

We all want Arlington and Massachusetts to remain welcoming, accessible places to live. In addition to our deficit of housing, I recognize the importance of encouraging smaller, more sustainable housing in walkable areas. Arlington’s Warrant Article 12 will provide a meaningful framework for making progress in these areas. The problems we are experiencing now —out of reach housing prices for new construction and existing homes — exacerbate the crisis and are seriously threatening the economic vibrancy of our communities.

To read Friedman’s full letter, click here for the PDF.

Why Is This Our Issue & What Should We Do About It?

(presented by Adam Chapdelaine, Town Manager, to Select Board on July 22, 2019)

Overview

Since 1980 the price of housing in Massachusetts has surged well ahead of other fast growing states including California and New York. While the national “House Price Index” is just below 400, four times what an average house might have cost in 1980, a typical house in Massachusetts is now about 720% what it was in 1980. Median household income in the state has only increased about 15% during the same period. No wonder people in Arlington are feeling the stresses of housing costs if they want to live here and are feeling protective of the equity value time has provided them if they bought years ago.

In response to concerns about zoning, affordable housing and housing density, the Town joined the “Mayors’ (and Managers’) Coalition on Housing” to address these growing pressures. This 12 page slide deck presentation outlines the key data points, the number of low and very low income households in Arlington, the rate of condo conversion that is absorbing rental units, etc.

Solutions are offered including:

• Amendments to Inclusionary Zoning Bylaw

• Housing Creation Along Commercial Corridor – Mixed Use & Zoning Along Corridor

• Accessory Dwelling Units – Potential Age & Family Restrictions

• Other Tools Can Be Considered That Are Outside of Zoning But Have An Impact on Housing

Chapdelaine’s suggested next steps are:

• Continued Public Engagement

• Town Manager & Director of DPCD Meet with ARB

• Select Board & ARB Hold Joint Meeting in Early Fall

• ARB Recommends Strategies to Pursue in Late Fall/Early Winter

The Select Board approved the suggested next steps and a joint ARB/ Select Board meeting should be scheduled in the near future.

Note from Reporter: As a community, Arlington has long prided itself on its economic diversity. With condo conversions, tear downs leading to “McMansions”, higher paid workers arriving in response to new jobs, etc., Arlington is at great risk of losing this diversity that has long enriched the community. Retirees looking to downsize and young people who have grown up in Arlington looking for their first apartment are finding it impossible to stay in town. Shop keepers and town employees are challenged to afford the rising housing costs. With a reconsideration of zoning along Arlington’s transit corridors, Arlington NOW has an opportunity to create new village centers, like those recommended in the recent STATE OF HOUSING report. These village centers along our transit corridors could be higher, denser but also offer the compelling visual design and amenities desired by people who want to walk to cafes, shops and public transit.

A study by Elise Rapoza and Michael Goodman shows that new housing construction in MA does not have an adverse affect on municipal or school budgets. And when it might, state funding covers the difference. This study contradicts the often heard argument against new housing development, especially multi-family housing, because it, the argument claims, it will have a negative fiscal impact on communities.

In the aggregate, development of new housing offers net fiscal benefit to both municipalities and the state. Additional analysis validates a second study which found that increased housing production does not predict enrollment changes in Massachusetts school districts. In the new study, a distinct minority of municipalities did incur net fiscal burdens—burdens that the net new state tax proceeds associated with the development of new housing are more than sufficient to offset.

A recently constructed project with 44 units of affordable housing shares a footprint with a new public library in this Chicago neighborhood. The Mayor and the Housing Authority initiated a competition for proposals from architecture firms to build projects that feature the “co-location” of uses, “shared spaces that bring communities together”, according to a recent article by Josephine Minutillo in ARCHITECTURAL RECORD (October 2019).

This project is an excellent example of how a municipal policy (increasing affordable housing) can drive creativity to meet policy goals. This project resulted from a combination of publicly owned land, municipal initiative, a quasi public housing agency expertise and a private architecture/ developer with a commitment to affordable housing. Could a project like this work in Arlington MA?

by Steve Revilak

On Tuesday August 6, 2024, Governor Healey signed the Affordable Homes Act (H.4977) into law. It’s a significant piece of legislation that will take positive strides toward addressing our state’s housing crisis. At 181 pages, the Affordable Homes Act is a lengthy bill, but the things it does generally fall into three categories: funding, changes to state law, and changes to state agencies.

The act authorizes more than five billion dollars to fund the creation, maintenance, and preservation of housing. This includes $425M to housing authorities and local housing initiatives (including $2.5M for the Arlington Housing Authority), $60M to assist homeowners or tenants with a household member with blindness or severe disabilities, $70M for community-based efforts to develop supportive housing for persons with disabilities, and $100M to expand opportunities for first-time homebuyers.

The Affordable Homes Act makes several changes to Massachusetts zoning laws, including the legalization of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) statewide. ADUs, also known as “granny flats” or “in-law apartments,” are a cost-effective way to add new housing, and they’re typically used to provide living quarters for relatives or caretakers, or to generate rental income for homeowners. ADUs are now allowed in all single-family zones in Massachusetts, by right, without the need for a discretionary permit. Arlington has been a leader in this area, having passed an ADU bylaw in 2021, and it’s great to see this option extended throughout the Commonwealth.

Finally, the Affordable Homes Act makes a number of changes to state agencies, especially the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC). The Act establishes a new Office of Fair Housing within the EOHLC, to “advance the elimination of housing discrimination.” The Fair Housing office will provide periodic reports on progress towards achieving this goal. EOHLC is also charged with creating and implementing a state-wide housing plan that will consider supply and demand, affordability, challenges unique to different regions of the state, and an analysis of local zoning laws.

While our legislators deserve kudos for putting this package together, they also deserve kudos for what they left out. More than three hundred amendments were filed during House deliberations, and a number of them were intended to weaken the multi-family housing requirements of the MBTA Communities Act. For example, one amendment, simply titled “Technical Correction” would have rewritten the transit community definitions, in order to reduce the housing requirements for Milton. We are heartened that our legislators did not go along with such shenanigans.