Related articles

According to Richard Rothstein in his 2017 book, Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, “we have created a caste system in this country, with African-Americans kept exploited and geographically separate by racially explicit government policies,” he writes. “Although most of these policies are now off the books, they have never been remedied and their effects endure.” Zoning was one of the policies that contributed significantly to this outcome.

Here are some highlights, selected for Arlington readers, from this book:

P. VII

“… until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state and local governments defined where white and African Americans should live. Today’s racial segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law and regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that is effects endure to the present time. Without our government’s purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causes – private prejudice, white flight, real estate starring, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregation – still would have existed but with far less opportunity for expression. Segregation by intentional government action is not de facto. Rather, it is what courts call de jure: segregation by law and public policy. “

1917 – Buchanan v. Warley – Supreme Court case that overturned racial zoning ordinance in Louisville, Kentucky. Municipalities ignore and fought against this. Kansas City and Norfolk through 1987.

- Post WWII GI Bill – African Americans largely excluded from education and mortgage benefits

- Federal Housing Administration won’t insure mortgages to African Americans or mortgages in integrated neighborhoods. African Americans limited to non-amortizing loans, which means they build no equity in their homes while making payments

- Federal, stage and local governments are used to enforce race-restrictive covenants in deeds.

1948 – Shelley v. Kraemer – Although racially restrictive real estate covenants are not per se illegal, since they do not involve state action, a court cannot enforce them under the Fourteenth Amendment. FHA continues to not insure mortgages for African Americans.

1968 – Fair Housing Act endorsed the rights of African Americans to to reside wherever they chose and could afford. Finally ending the Federal Housing Administration’s’ role in mortgage insurance discrimination.

1969 – Mass 40B law passed

1972 – Head of Arlington ARB editorial talking about preserving the suburban way of life

1973 – Town Meeting passes moratorium on apartment construction

1975 – Arlington zoning re-do that all but stops development

1977 – Supreme Court upholds Arlington Heights, IL zoning that prohibited multi-unit development anywhere by adjacent to an outlying commercial area. In meetings leading to the adoption of these rules, the public urged support for racially discriminatory reasons.

p. 179″Residential segregation is hard to undo for several reasons:

- Parents’ economic status is commonly replicated in the net generation, so once government prevented African Americans from fully participating in the mid-twentieth-century free labor market, depressed incomes became, for many, a multi-generational trait

- The value of white working and middle-class families’ suburban housing appreciated substantially over the years, resulting in a vast wealth difference between whites and blacks that helped to define permanently our racial living arrangements. Because parents can bequeath assets to their children, the racial wealth gap is even more persistent down through the generations than income differences.

- Once segregation was established, seemingly race-neutral policies reinforced it to make remedies even more difficult. Perhaps most pernicious has been the federal tax code’s mortgage interest rate deduction, which increased the subsidies to higher-income suburban homeowners while providing no corresponding tax benefit for renters. Because de jure policies of segregation ensured that whites would be more likely to be owners and African Americans would more likely be renters, the tax code contributes to making African Americans and whites less equal, despite the code’s purportedly nonracial provisions.

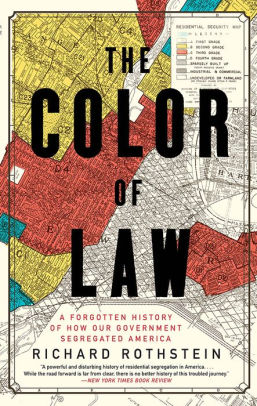

from Alexandra P. Levering , Thesis, Urban & Environmental Policy and Planning, Tufts University, August 2017

By 2017 65 out of 101 municipalities in the greater Boston (MAPC) region allowed Accessory Dwelling Units by right or by special permit. The average number of ADU’s added per year was about 3. But by 2017, Lexington had 75 ADUs, Newton had 73 and Ipswich had 66. It is a slow process for a variety of reasons, but the number of units grows over time.

AARP recommends ADU’s. The help homeonwers cover rising housing costs by providing income trhough rent. They also create a space for a caretaker or a family member to live close by, as the homeowner ages.

Autism Housing Pathways and Advocates for Autism of MA (AFAM) came together to advocate for an ADU bylaw to benefit parents of adult children with disabilities. For more information see her complete thesis (with a very useful set of tables and bibliography) HERE.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) provide multigenerational housing options for aging parents and for adult children. They help families manage changing lifestyle, fiscal and/or caretaking situations.

This type of housing is seen by many as a clear opportunity to offer more affordable residential opportunities. One reason why they are slow to develop is the cost of renovation and construction for homeowners. Some communities offer low or no interest loans to encourage more ADU development.

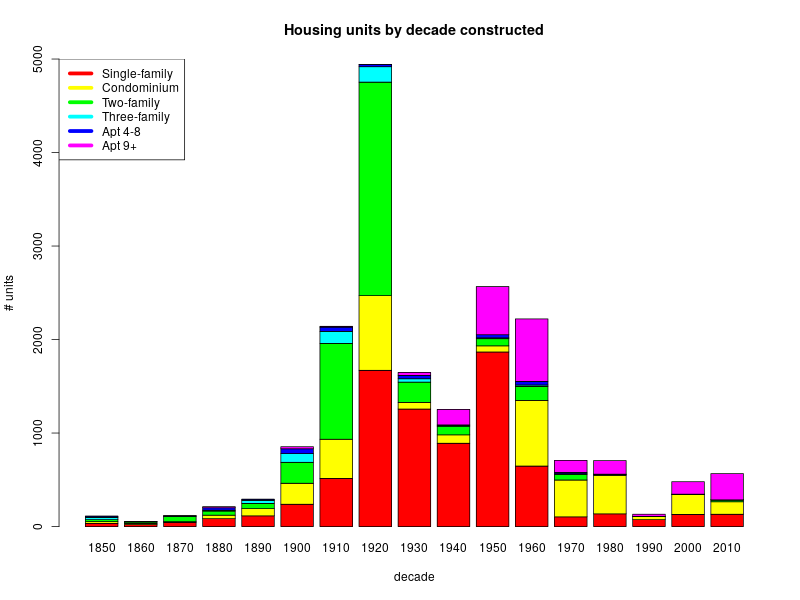

The material in this post came from my efforts to learn about when Arlington’s housing was built. The data comes from the town’s 2019 property tax assessments, where I took our nineteen-thousand-and-some-odd homes and apartments and broke them down by housing type and decade built. It’s not exactly a history housing of production, though it is a close approximation. In this analysis, a single-family home built in the 1912 and rebuilt as a two-family in 1976 would show up as two units built in the 1970s. Similarly, a three-family home that was built in the 1924 and later converted to condominiums would show up as three condominiums built in the 1920s.

Here’s the visual summary:

And here’s a small spreadsheet with the underlying numbers.

My first surprise was at how much we built in the 1920s: just under five thousand units. This was our biggest decade for housing production, and nearly double our second biggest (the 1950s). Another surprise was the 1990s; 132 of our homes were constructed during that decade, which is the smallest number since the 1870s.

What about homes constructed before 1850? There are only 117 of them, and they’re omitted from the data set. I’ve also omitted residential units in mixed-use buildings, since my copy of the assessors data doesn’t break mixed-use buildings into residential and non-residential units.

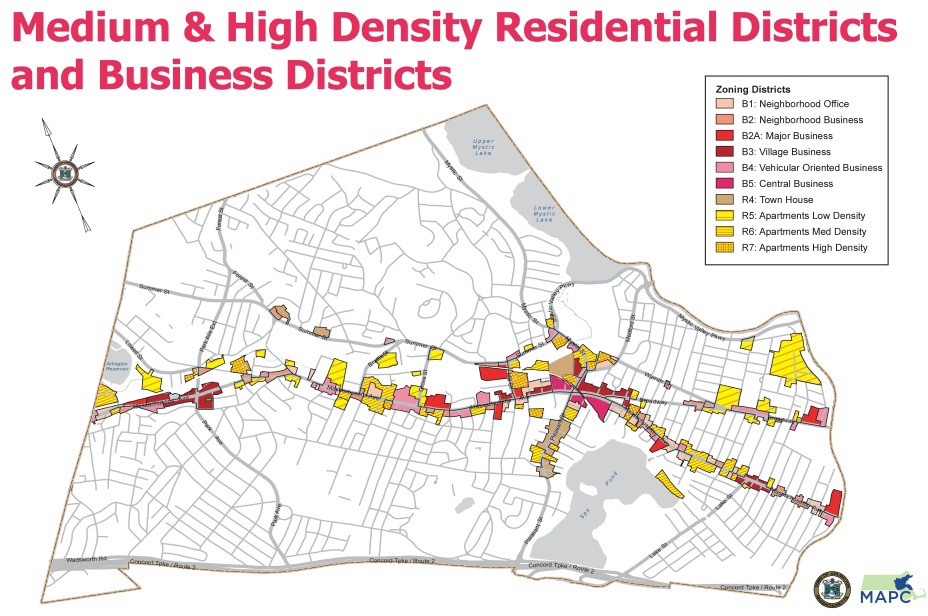

The discussions on zoning have been confusing because while zoning covers ALL of Arlington’s land and the zoning bylaws for all Arlington’s zones are referenced, the key issues of greatest interest to Town Meeting are the discussions about increasing density. These discussions pertain ONLY to those properties currently zoned as R4-R7 and the B (Business) districts. These density related changes would affect only about 7% of Arlington’s land area. The map shows the specific zones that would potentially be affected. They lay along major transportation corridors.

A study by Elise Rapoza and Michael Goodman shows that new housing construction in MA does not have an adverse affect on municipal or school budgets. And when it might, state funding covers the difference. This study contradicts the often heard argument against new housing development, especially multi-family housing, because it, the argument claims, it will have a negative fiscal impact on communities.

In the aggregate, development of new housing offers net fiscal benefit to both municipalities and the state. Additional analysis validates a second study which found that increased housing production does not predict enrollment changes in Massachusetts school districts. In the new study, a distinct minority of municipalities did incur net fiscal burdens—burdens that the net new state tax proceeds associated with the development of new housing are more than sufficient to offset.

Minneapolis is the most recent governmental entity to disrupt the almost 110 year old idea of local zoning in America by overriding single family zoning. Zoning was developed in the the early 1900’s to control property rights and, in part, to limit access to housing by race. These early laws were upheld by the courts in the 1930’s and the use of zoning to control private property for the interests of the majority became common. Houston Texas did not adopt zoning, an outlier in the nation.

But recently governments are rethinking zoning in light of evidence of exclusionary practices including racism and inadequate supplies of affordable housing. In July Oregon’s legislature voted to essentially ban single family zoning in the state.

Most recently, in the end of July, Minneapolis became the first city this century to remove single family zoning, allowing two family housing units to enter any single family zone as of right. According to the Bloomberg News article, the city took action to remedy the untenable price increases do to single family homes taking a disproportionate amount of city land and services. They hope a wider range of housing, and more housing, will reduce housing costs in the future.

Read the full story from Bloomberg News.

The cost of building a residential unit, single or multi-family, correlates directly, if not precisely, with its cost to resident tenants or owners. The following study and data (using Assessor’s data) demonstrates that higher density housing is more affordable than single-family housing. Whether you look at the median cost of all housing across the Town or the unit costs of the newer, more expensive, apartments built in the last decade, density yields lower prices. The town wide median is $438,900 per unit.

The newest projects (420-440 Mass Ave., Brigham Square and Arlington 360) range from $249k per unit to $412K per unit. These three developments alone contributed 414 new units of housing to the Town.

Discussions of “affordability” represents a spectrum of terms. Units can be affordable because zoning and market conditions allow the units to be built for less money than a single family home. Or they can be affordable because the builder has received subsidies that reduce the cost. Or they can be affordable, as in the case of inclusionary zoning, because the permission to build is contingent on at least some of the units being “permanently” (99 years) available to qualified tenants or buyers based on legal restrictions.

It’s the time of year when folks in Arlington are taking out nomination papers, gathering signatures, and strategizing on how to campaign for the town election on Saturday April 1st. The town election is where we choose members of Arlington’s governing institutions, including the Select Board (Arlington’s executive branch), the School Committee, and — most relevantly for this post — Town Meeting.

If you’re new to New England, Town Meeting is an institution you may not have heard of, but it’s basically the town’s Legislative Branch. Town Meeting consists of 12 members from each of 21 Precincts, for 252 members total. Members serve three-year terms, with one-third of the seats up for election in any year, so that each precinct elects four representatives per year (perhaps with an extra seat or two, as needed to fill vacancies). For a deeper dive, Envision Arlington’s ABC’s of Arlington Government gives a great overview of Arlington’s government structure.

As our legislative branch, town meeting’s powers and responsibilities include:

- Passing the Town’s Operating Budget, which details planned expenses for the next year.

- Approving the town’s Capital Budget, which includes vehicle and equipment purchases, playgrounds, and town facilities.

- Bylaw changes. Town meeting is the only body that can amend the towns bylaws, including ones that affect housing — what kinds can be built, how much, and where.

Town Meeting is an excellent opportunity to serve your community, and to learn about how Arlington and its municipal government works. Any registered voter is eligible to run. If this sounds like an interesting prospect, we encourage you to run! Here’s what you’ll need to do:

- Have a look at the town’s Information for new and Prospective Town Meeting Members.

- Contact the Town Clerk’s office to get a set of nomination papers. You’ll need to do this by 5:00 PM February 12th, 2025 at the latest.

- Gather signatures. You’ll need signatures from at least ten registered voters in your precinct to get on the ballot (it’s always good to get a few extra signatures, to be safe).

- Return your signed nomination papers to the Clerk’s office by February 14, 2025 at 5:00 PM.

- Campaign! Get a map and voter list for your precinct, knock on doors, and introduce yourself. (Having a flier to distribute is also helpful.)

- Vote on Saturday April 5th, and wait for the results.

Town Meeting traditionally meets every Monday and Wednesday at 8:00 PM, starting on the 4th Monday in April (which is April 28th this year), and lasting until the year’s business is concluded (typically a few weeks).

If you’d like to connect with an experienced Town Meeting Member about the logistics of campaigning, or the reality of serving at Town Meeting, please email info(AT)equitable-arlington.org and we’d be happy to make an introduction.

During the past few years, Town Meeting was our pathway to legalizing accessory dwelling units, reducing minimum parking requirements, loosening restrictions on mixed-use development in Arlington’s business districts, and adopting multi-family zoning for MBTA Communities. Aside from being a rewarding experience, it’s a way to make a difference!